18-4-2005

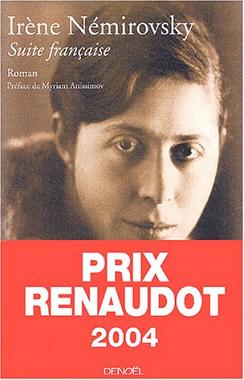

SUITE

FRANÇAISE, de Irène

Némirovsky

LINTERN@UTE

MAGAZINE

Qui est... Irène Némirovsky ?

|

Irène Némirovsky est originaire de Kiev, née en 1903 dans une famille de

financiers juifs russes. Son père, Léon Némirovsky, était un des plus riches

banquiers de Russie ; la jeune fille connut une enfance particulièrement

heureuse à Saint-Petersbourg. Elle y apprit d'ailleurs le français avant de

connaître le russe. Mais lorsque la révolution éclate dans le pays en 1917, Léon

Némirovsky préfère éloigner sa petite famille du pays en crise et s'installe en

France en juillet 1919. Irène reprend alors brillamment ses études et décroche

en 1926 sa licence de lettres à la Sorbonne.

1926 est une année clé de la vie de la jeune femme, puisqu'elle publie son

premier roman Le Malentendu (même si elle avait déjà publié auparavant

quelques contes et nouvelles, et ce dès 1923) et épouse un homme d'affaires

juif russe, Michel Epstein. En 1929, elle donne naissance à sa

première fille, Denise, et publie la même année David Golder, son premier grand succès,

adapté au théâtre et au cinéma. |

|

|

|

Le Bal, l'année suivante, raconte le

passage difficile d'une adolescente à l'âge adulte. L'adaptation au cinéma

révèlera Danielle Darrieux. De succès en succès, Irène Némirovsky devient une

égérie littéraire, amie de Kessel et Cocteau, et donne naissance en 1937 à sa

seconde fille, Elisabeth.

La Seconde Guerre mondiale mettra un terme brutal à ce brillant parcours. En

1938, Irène Némirovsky et Michel Epstein se voient refuser la nationalité

française, mais n'envisagent toutefois pas l'exil, persuadés que la France

défendrait ses juifs. Ils préfèrent toutefois envoyer leurs deux filles dans le

Morvan. Lâchée par ses amis et son éditeur, Irène porte l'étoile jaune. Elle

rejoint, accompagné par son mari, ses deux filles dans le petit village où elles

étaient cachés. C'est là qu'Irène Némirovsky rédigera le récit de Suite

française, persuadée qu'elle allait bientôt mourir.

Elle est arrêtée devant ses enfants par les gendarmes en juillet 1942, et

envoyée à Auschwitz, où elle succombera du typhus quelques semaines plus tard.

Michel Epstein, qui avait tout tenté pour sauver sa femme, est également déporté

en novembre et immédiatement gazé à son arrivée. Ses deux filles sauvent

quelques documents, puis sont placées sous la tutelle d'Albin Michel et Robert

Esmenard (qui dirigea la maison d'édition) jusqu'à leur majorité.

Les deux filles ont entretenu la mémoire de leur mère, avec plusieurs rééditions

et la publication d'une biographie en 1992, Le Mirador. En 2004, Denise

Némirovsky découvre au fond d'une malle le manuscrit inachevé de Suite

française, qui raconte, entre autres, l'exode de juin 1940, faits de

lâchetés et de petits élans de solidarité. Elle se décide à le publier, et le

roman a la surprise de se voir consacré du prestigieux prix Renaudot. Surprise,

car c'est la première fois dans son histoire que le prix est remis à un auteur

disparu. Mais ce n'est que justice quand on sait que jamais Irène Némirovsky

n'avait été distinguée de son vivant.

[Johann

Liard, L'Internaute]

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Le

Malentendu (1926)

L'Enfant

génial (1927)

David

Golder (1929)

Le

Bal (1930)

Les

Mouches d'automne (1931)

L'affaire

Courilof (1933)

Films

parlés (1934)

Le

Pion sur l'échiquier (1934)

Le

Vin de solitude (1935)

Jézabel

(1936)

La

Proie (1938)

Deux

(1939)

Les

Chiens et les loups (1940)

La

Vie de Tchekov (posthume, 1946)

Les

Biens de ce monde (posthume, 1947)

Les

Feux de l'automne (posthume, 1957)

Dimanche

et autres nouvelles (posthume, 2000)

Destinées

et autres nouvelles (posthume, 2004)

Suite

française (posthume, 2004)

Le Renaudot à feue Irène Némirovsky

C'est

la première fois que le prix est attribué à un auteur disparu.

lundi 08 novembre 2004 (Liberation.fr -

16:41)

|

Le

prix Renaudot 2004 va à Irène Némirovsky, auteur disparue, pour «Suite

française» (Denoël). Elle l'a emporté au 2e tour par 6 voix contre 3 à Marc

Lambron («Les menteurs», Grasset) et 1 à Philippe Ségur («Poétique de

l'égorgeur», Buchet-Chastel). C'est la première fois que le Renaudot récompense

le livre d'un auteur disparu. «Un tel choix nous fait sortir de nos statuts,

sauf que le livre est un très beau livre. Mais, quand même, il faut se souvenir

que les prix sont faits pour promouvoir un écrivain. On n'est pas là pour

rattraper les injustices des morts. Et pourquoi pas l'an prochain couronner un

inédit d'Alexandre Dumas?», a déclaré lundi le secrétaire général du prix

Renaudot, André Brincourt, exprimant son désaccord avec le choix du jury.

Née en 1903 à

Kiev, d'origine juive ukrainienne, Irène Némirovsky, exilée à Paris, a rencontré

le succès en 1929 avec son roman «David Golder». Amie de Kessel et Cocteau,

encensée par la critique, auteur d'une quinzaine de titres, elle se cache

pendant la guerre dans le Morvan. Arrêtée par les gendarmes français, puis

déportée, elle succombe à Auschwitz en 1942. Le roman primé raconte —dans la

partie intitulée «Tempête en juin»— l'exode de juin 40, montrant «les petites

lâchetés et les fragiles» élans de solidarité d'une population en déroute.

L'autre partie, «Dolce», décrit un village français, Bussy, contraint

d'accueillir des troupes allemandes. |

|

|

|

Agée de 13 ans

lors de l'arrestation de sa mère, sa fille aînée, Denise (lire

son portrait,

réussit à sauver des manuscrits, parmi lesquels le texte de «Suite française».

La fille cadette d'Irène Némirovsky, Elisabeth Gille -elle-même directrice de

collection chez Denoël- avait publié en 1993 une biographie de sa mère intitulée

«Le mirador». Elisabeth Gille est morte depuis d'un cancer. Dès sa parution, le

livre a connu un grand succès et les droits ont été achetés par de nombreux pays

étrangers.

Le Renaudot de

l'essai a été attribué à Evelyne Bloch-Dano pour «Madame Proust» (Grasset),

biographie de la mère du romancier. A la question : «Quel serait votre plus

grand malheur?», Marcel Proust avait répondu : «Etre séparé de maman.» Evelyne

Bloch-Dano reconstitue la vie quotidienne de Jeanne Proust, une mère aimante

«muée en vestale», autant collaboratrice que gouvernante. Née Weil en 1849 dans

une famille juive venue d'Alsace et d'Allemagne, elle est «omniprésente de son

vivant mais aussi après sa mort, dans l'œuvre de son fils», souligne l'auteur.

Elle raconte son mariage avec Adrien Proust, fils d'épicier catholique

beauceron, sans fortune mais promis à une brillante carrière médicale.

Possessive, elle a accepté «les ruses et les foucades» d'un enfant malade et

gâté qui dort le jour et travaille la nuit. A sa mort, en 1905, Marcel écrivit :

«Ma vie a perdu son seul but, sa seule douceur, son seul amour, sa seule

consolation.» Evelyne Bloch-Dano, agrégée de lettres modernes, est également

l'auteur, chez Grasset, de la première biographie de Madame Zola (1998, Grand

Prix des lectrices de Elle, 30.000 exemplaires vendus) et d'une biographie de

Flora Tristan (2001).

Sur le Web

Le site des

Editions Denoël

Le site

Irène Némirovsky

Le site des

Editions Grasset

ARTICLE PARU DANS

L'EDITION DU 10.11.04

Le Renaudot

attribué, à titre posthume, à Irène Némirovsky

LE

MONDE | 09.11.04

Le

Goncourt récompense pour la première fois Actes Sud pour un livre de Laurent

Gaudé,"Le Soleil des Scorta".

Lundi

8 novembre, le prix Goncourt a récompensé Actes Sud pour la première fois depuis

sa fondation à Arles, en 1978, par Hubert Nyssen. Une maison qui publie beaucoup

de romanciers étrangers, notamment l'Américain Paul Auster, et qui, en 2002, a

eu la chance de voir un de ses auteurs, le Hongrois Imre Kertész, obtenir le

prix Nobel de littérature.

Au

Goncourt, Actes Sud avait déjà eu six fois des auteurs parmi les finalistes,

mais le prix était toujours revenu à un éditeur parisien. Le lauréat 2004,

Laurent Gaudé, était dans la dernière sélection en 2002 avec

La Mort du roi Tsongor,

mais il avait finalement été battu par Pascal Quignard (Les

Ombres errantes, Grasset) : Laurent Gaudé avait alors obtenu le Goncourt des

lycéens. Cette année, il est le lauréat pour Le Soleil des Scorta, au

quatrième tour de scrutin, par 4 voix contre 3 à Alain Jaubert pour Val

Paradis (Gallimard, "L'infini") et 2 à Marc Lambron pour Les Menteurs

(Grasset).

Un

prix qui "n'allait pas de soi", selon Edmonde Charles-Roux, présidente de

l'académie Goncourt, aujourd'hui réduite à neuf membres après la mort d'André

Stil. Le nouveau juré, Bernard Pivot, ne rejoindra l'académie qu'en 2005. "La

rentrée littéraire est brillante, et chaque livre auquel on renonçait posait

problème, a précisé Mme Charles-Roux. La discussion a duré une

heure et quart. C'est la preuve que cela n'allait pas de soi. Les journalistes

qui nous accusent et prétendent que tout est couru d'avance se sont cruellement

trompés." Les journalistes donnaient toutefois Laurent Gaudé favori depuis

plusieurs semaines, comme l'a rappelé le Journal du dimanche.

Le

Soleil des Scorta est

seulement le troisième roman du dramaturge Laurent Gaudé, 32 ans. Après s'être

tourné vers une Afrique ancestrale à travers les aventures du vieux Tsongor, roi

de Massaba, dans La Mort du roi Tsongor, Gaudé va, cette fois-ci, dans la

même veine épique, du côté de l'Italie, suivant le destin d'une famille, de 1870

à nos jours, sur cinq générations. Une famille, les Scorta, portant un lourd

secret, un viol sur lequel elle s'est fondée, et tentant d'échapper à un destin

misérable sur la terre ingrate des Pouilles, dans un village perdu, Montepuccio

("Le Monde des livres" du 8 octobre).

MORTE EN 1942

Au

prix Renaudot, on remarque aussi une première. La lauréate est Irène Némirovsky,

pour Suite française (Denoël), au second tour de scrutin, par 6 voix

contre 3 à Marc Lambron et une à Philippe Ségur pour Poétique de l'égorgeur

(éd. Buchet-Chastel). Romancière d'origine russe, Irène Némirovsky commença une

brillante carrière dans l'entre-deux-guerres. Juive, elle fut déportée à

Auschwitz, où elle est morte le 17 août 1942. Certaines de ses œuvres avaient

été rééditées (Grasset "Cahiers rouges"), mais sa fille, Denise Epstein,

possédait le dernier manuscrit de sa mère, demeuré inédit, et l'a fait publier

cet automne.

Le

secrétaire général du Renaudot, André Brincourt, a immédiatement exprimé son

désaccord : "Un tel choix nous fait sortir de nos statuts, sauf que le livre

est un très beau livre. Mais quand même, il faut se souvenir que les prix sont

faits pour promouvoir un écrivain. On n'est pas là pour rattraper les injustices

des morts. Et pourquoi pas l'an prochain couronner un inédit d'Alexandre Dumas

?" Jusqu'alors le règlement du prix précisait seulement : "Pour les

essais, il peut s'agir de rééditions et l'auteur couronné l'être à titre

posthume." La plupart des jurés se refusent à commenter les débats, estimant

qu'ils doivent rester "internes". Toutefois Franz-Olivier Giesbert estime

que "tout simplement, le prix doit revenir à un bon livre qui vient de

sortir. C'est le cas. Donc il n'y a aucun problème." Patrick Besson, qui a

voté pour Irène Némirovsky, précise cependant qu'"il

ne faudrait pas que ça devienne une habitude".

Le

roman d'Irène Némirovsky, Suite française, devait comporter 5 tomes. On

ne possède que les deux premiers, publiés aujourd'hui en un volume et deux

parties La première, "Tempête en juin", évoque l'exode de 1940. La seconde,

"Dolce", décrit un village français contraint d'accueillir des troupes

allemandes. Le centre du livre est occupé par l'amitié d'une jeune femme restée

seule avec sa belle-mère, pour un officier allemand raffiné ("Le Monde des

livres" du 1er octobre).

Le

prix Renaudot de l'essai est revenu à Evelyne Bloch-Dano pour Madame Proust

(Grasset), la biographie de la mère de Marcel Proust. Au Goncourt des lycéens,

le choix s'est porté sur Philippe Grimbert pour Un secret (Grasset),

roman paru au printemps ("Le Monde des livres" du 28 mai). Après La Petite

Robe de Paul (Grasset), le psychanalyste, dans ce roman autobiographique,

décrypte le lourd secret et les mystères de la naissance d'un enfant conçu à la

toute fin de la seconde guerre mondiale, au moment de la Libération. Ce fils

unique, qui s'était rêvé un frère, découvre soudain, à l'âge de 15 ans,

l'existence et l'histoire de cet aîné.

Auschwitz victim's book causes a

stir in France

By

Colin Randall in Paris

(Filed:

23/10/2004)

A hidden literary treasure of

wartime France is taking the book world by storm, while reviving uncomfortable

memories of French collaboration with the Nazis, more than 60 years after its

author was sent to her death in Auschwitz.

Irene Nemirovsky's Suite Française,

transcribed and edited by her elder daughter, who clung to the manuscript as a

keepsake of her mother, has been sold to publishers in 17 countries in an

extraordinary bidding war.

The book combines two novels, one

dealing with the flight of Jews from Paris during the great exodus of 1940 and

the second with the early period of Nazi occupation.

It has won acclaim from French

critics, with calls for a posthumous award when the Goncourt prize, the

country's premier book award, is announced next month.

Suite Française - the completed half

of what Nemirovsky planned as the four-volume "work of my life" - is regarded by

some commentators as the most important descriptive wartime writing since Anne

Frank's Diaries.

From the appearance of her first

novel, David Golder, in 1929, when she was 26, Nemirovsky was feted as the

darling of Parisian literary society. But she was also a Jew, born in Kiev to a

prosperous banker's family. When the Germans invaded France, Nemirovsky was

deserted by almost all those who had previously sought her company and admired

her work.

Despite appeals to the German

ambassador to Paris and Marshal Petain, the leader of the puppet Vichy regime,

she was arrested by gendarmes and deported to Auschwitz in July 1942, dying of

typhus a month later at the age of 39.

Her conversion to Roman Catholicism

as war broke out, and her family's move from Paris to Burgundy, failed to save

her. Her husband, Michel Epstein, was detained later along with his two brothers

and sister. They, too, perished, almost certainly in the Auschwitz gas chambers.

Nemirovsky's daughters, Denise and

Elisabeth, were spared, apparently because they reminded a German officer of his

own child. For the rest of the war, they were cared for by a Catholic woman who

moved them from one safe house to another. In a suitcase carried on each of a

dozen moves, Denise Epstein kept the leather-bound notebooks containing her

mother's last writings.

"I never opened it until 1954," said

Miss Epstein, now 75. "It made me angry to read it. Seeing my mother's wonderful

lucidity just gave me a tremendous sensation of abandonment."

Not until the 1970s did she open the

book "properly", after her Paris home was flooded and she decided to move it to

the safety of a shelf.

The first novel, Storm in June, was

typed. The second, Dolce, written as paper became scarce, was in minute

handwriting.

Over the next 20 years. Miss Epstein

painstakingly read and transcribed, over and over again, her mother's text.

"She could look inside the human

soul and make music with her words. But it is only now that I can look at it as

a reader rather than as my mother's daughter," she said.

The success of Suite Française is

encouraging news for an American academic who researched his own biography of

Nemirovsky only to be told it was not marketable.

Prof Jon Weiss, who lectures in

French and 20th century French literature at Colby College, Maine, described

Nemirovsky as "an enigma and an absolutely fantastic novelist of the 1930s".

The Longest Journey

A novel hidden since World War II sees the light of day.

By Eric Pape

Nov. 29 issue -

"I am going on a

journey," Irene Nemirovsky told her two young daughters on July 13, 1942, before

leaving their village with French gendarmes. By then, Nemirovsky, a writer and a

Jew, had no illusions about French collaboration with the Nazis; it was the

focus of the second tome of a novel that she had just finished. Five weeks later

she died at Auschwitz at the age of 39.

When the Nazis came for her husband

two months later, a German officer took pity on the children: run home, take

what you can and disappear, he told them. They grabbed their mother's suitcase,

which included her last leatherbound writings, as well as family photos and

tchotchkes. From an orphanage to cellars to attics, the girls carried the bag

everywhere, waiting out the war. Amazingly, they didn't read the words, for fear

of the painful memories. Only three decades later—after flooding nearly

destroyed the volume—did the older daughter, Denise Epstein, begin transcribing

the handwritten pages. Now Epstein has decided to share her discovery.

The two-part book, "Suite Française"

(430 pages. In French by Denoel),

is a sort of Anne Frank occupation-testimonial meets "War and Peace." The

first part, "Tempete en Juin" (Tempest in June), offers penetrating snapshots of

flawed refugees fleeing France in 1940 on bikes, horses, cars and foot ahead of

the German advance. The second part, "Dolce" (Desserts), which Nemirovsky

finished days before her arrest, is a more literary tale about the sprouting

seeds of collaboration in an occupied village.

Nemirovsky conjures up the

hatefulness of small-time theft and betrayal for petty gain, even as the world

goes to hell, as well as the breakdown of orphans murdering their abbot, and

mothers abandoning their children. Hers is a defeated nation, losing its soul,

but not necessarily on the battlefield. "What interests me isn't the history of

the world," she writes. "It must brush on historic events, but more deeply, it

is about daily life, emotional life, and the absurdity [comedie]

that this presents."

The book has sparked a literary

resurrection. Nemirovsky was one of the most renowned writers of her generation,

admired for 13 novels, many of which cast an acerbic eye on high society. But

she was quickly forgotten in the shadow of her fate. When "Suite Française" was

published on September 30, it quickly sold 45,000 copies—and that was before it

received the prestigious Renaudot literary prize two weeks ago, the first time

the award has been granted posthumously. At the Frankfurt Book Fair in early

October, rights to the book were sold in at least 19 countries.

"Never forget that the war will pass

and that the whole historical part will pale," Nemirovsky wrote. "Try to do as

many things... as possible to interest people in '52 or 2052." Sixty years after

her death, she has clearly succeeded.

LEFIGARO

littéraire

9-11-2004

Irène

Némirovsky : échec à l'oubli

Par

Clémence Boulouque

SUITE

FRANÇAISE d'Irène Némirovsky. Préface de Myriam Anissimov.

Denoël, 430 pages,

22 €.

Autant qu'une

consécration, c'est une justice faite, enfin faite – la reconnaissance d'une

romancière qui a donné aux lettres françaises d'admirables pages et qui a été

sacrifiée par Vichy, dont les fonctionnaires de police vinrent l'arracher aux

siens, durant l'été 1942, avant de l'envoyer à Auschwitz, où elle mourut

quelques semaines plus tard.

Née en Ukraine en 1903 dans une famille de banquiers, Irène Némirovsky connaît

une enfance privilégiée auprès de sa nourrice qui lui apprend le français, mais

ce sont des années de tristesse car sa mère est peu aimante. Elle vit la

Révolution russe dans un appartement moscovite, où le fracas du monde lui

parvient, trouant la bulle où l'enferme Le Portrait de Dorian Gray d'Oscar

Wilde. Après un premier exil en Finlande, le temps d'une brève saison, la

famille gagne la France. C'est pour Irène le Paris des années dites «folles», le

temps des bals et la fréquentation de l'émigration russe – dont l'observation

nourrira Les Mouches d'automne. Elle donne quelques nouvelles à des revues et

envoie anonymement, en 1929, un premier roman, David Golder, à Grasset. La

chronique de cet homme d'affaires sans scrupule et de sa chute sont d'une acuité

qui laisse deviner son auteur sous d'autres traits que ceux d'une jeune mère, et

qui tarde à répondre aux lettres de Bernard Grasset, adressées poste restante,

car elle relève de couches. Devenue l'enfant chéri des «Lettres parisiennes»,

saluées par Brasillach, Cocteau ou Kessel, elle voit son roman adapté par Julien

Duvivier, dès 1930, avec Harry Baur dans le rôle titre. La précision de son

observation et son empathie lui permettent d'atteindre à une justesse de la

langue, des esprits et des images, qui donnent à son oeuvre une dimension

naturellement cinématographique. Son court texte, Le Bal, écrit pour se délasser

entre deux chapitres de David Golder, devient, d'ailleurs, un film en 1931,

marquant les débuts de Danielle Darrieux dans le septième art.

Les douze livres d'Irène Némirovsky ont en commun le refus de toute

appartenance. Ils promènent un regard perçant, sur toutes les classes sociales,

et valent à celle qui s'en sert, l'étiquette de «juive antisémite». Assimilée,

persuadée d'être protégée par la République française, Irène Némirovsky, tout

comme son mari, sous-estime la montée des périls. Installée en Saône-et-Loire

après l'exode, elle est arrêtée en 1942. Les démarches de la femme de Paul

Morand, qui tente d'intercéder auprès de Pétain, seront vaines – dans sa

réponse, il envoie copie du statut des apatrides. Seul Albin Michel fait preuve

de dignité dans cette triste course à l'abîme, en accordant une pension à son

auteur et en protégeant ses filles à la fin de la guerre.

Suite française est le roman, composé de deux volets, de cette époque. La jeune

femme avait l'ambition d'en faire Guerre et Paix. On ne se retient pas d'évoquer

une observation de la bêtise à la Bouvard et Pécuchet à travers le personnage

d'un écrivain parisien bouffi de suffisance. Ni une peinture balzacienne de la

bourgeoisie provinciale. Et l'on pense également au Silence de la mer, de

Vercors, avec l'analyse des sentiments naissants entre une jeune femme et un

officier allemand. Après avoir mis en sécurité le texte au moment de

l'arrestation de sa mère, Denise Epstein l'a conservé par-devers elle dans un

petit cartable, durant la guerre et a laissé de longues années couler sur cette

douleur. Sa soeur, Elisabeth Gille, avait romancé la vie d'Irène en 1992 dans Le

Mirador, peu avant d'être emportée par un cancer. C'est une rencontre avec

Myriam Anissimov (qui signe une remarquable préface) qui a convaincu Denise

Epstein de se dessaisir de son trésor, de cette voix maternelle qui montait du

fond du gouffre. Il convient aussi de rendre hommage à ces gardiennes de la

mémoire.

Véritable événement de la foire de Francfort, Suite française a été acheté par

19 pays, et s'était vendu, en France, à 45 000 exemplaires avant même l'annonce

du prix.

En attribuant le prix Renaudot à Irène Némirovsky, les membres du jury offrent

donc à un public plus vaste, la possibilité de découvrir une oeuvre qui compte.

Certains verront là des intentions d'ordre extralittéraire. A ces considérations

chagrines, on préférera d'autres pensées. C'est une certaine vision des lettres,

qui prévaut aujourd'hui avec ce choix. Ce prix est comme une réparation. La

littérature, échec infligé à l'oubli. Irène Némirovsky n'a de sépulture que son

oeuvre. Visiter la sienne, dans ses pages, est un devoir que récompense, pour le

lecteur, un éblouissement.

30-9-2004

Le Monde des

livres

Sauvé

par sa fille Denise, le dernier manuscrit de la romancière, déportée et

assassinée à Auschwitz, a attendu plus d'un demi-siècle pour être enfin publié.

Le

Guerre

et paix

d'Irène Némirovsky

Par

René de Ceccatty

Elisabeth Gille

dédiait en 1992, quatre ans avant sa mort, Le Mirador, la biographie de sa mère,

Irène Némirovsky, à sa sœur, Denise Epstein, "la mémoire douloureuse". Or, voilà

que douze ans plus tard, soixante-deux ans après la mort d'Irène Némirovsky,

déportée le 13 juillet 1942 et assassinée le 17 août à Auschwitz, cette "mémoire

douloureuse" arrache à l'oubli un chef-d'œuvre : les deux premiers tomes d'une

Suite française, prévue pour en comporter cinq et ici parue en un seul volume.

Le manuscrit avait été emporté par la toute jeune Denise dans sa fuite vers

Bordeaux.

Le cas tragique

d'Irène Némirovsky occupera longtemps la mauvaise conscience française.

Romancière russe et juive, émigrée dans son enfance avec ses parents en France,

via la Finlande, juste après la guerre de 1914, elle s'intègre très rapidement

dans le monde littéraire parisien. David Golder (Grasset, "Cahiers rouges"),

qu'elle commence à écrire à 22 ans, paraît quand elle en a 26, en 1929. Dès

lors, elle publie coup sur coup douze autres livres, chez Grasset, Gallimard et

Albin Michel. Le patron de cette dernière maison, Robert Esménard, aura, au

moment des lois raciales, une conduite exemplaire, pour assurer la survie de cet

auteur, qui jouissait d'un véritable consensus littéraire.

La lecture de

Suite française révèle un pessimisme cynique, orienté moins vers l'abomination

nazie et antisémite (à laquelle il n'est, c'est un comble, fait presque aucune

allusion) que vers la bassesse humaine. Au cœur de la tourmente, elle-même

contrainte à l'exode avec ses filles (elles s'installent à Issy-l'Evêque, en

Saône-et-Loire), Irène Némirovsky entreprend de décrire ce qui l'entoure. Elle a

en tête son Guerre et paix. Son expérience littéraire, la dureté de son regard

sur l'humanité, son absence radicale de sentimentalisme, d'autocomplaisance,

d'humanisme bon ton donnent à son tableau une vigueur dérangeante. Elle

détestait toute conduite commandée par l'appartenance à une classe, à une

collectivité. Elle était issue d'une bourgeoisie dont elle avait haï et

vilipendé les défauts à travers sa propre mère, comme le montrent Le Bal

(Grasset, "Cahiers rouges") ou Jézabel. Cette même bourgeoisie, elle la

contemple dans le désastre. Elle la confronte à des classes populaires, petits

commerçants ou paysans, dont elle sait également traquer la veulerie. Et

parfois, soudain, un personnage bénéficie d'une sorte de grâce, d'un crédit

d'ingénuité, d'une noblesse réelle.

Le centre du

livre est occupé par l'amitié d'une jeune femme mal mariée, balzacienne, restée

seule avec sa belle-mère, pour un officier allemand raffiné. Le Silence de la

mer préfiguré ? Mais cet épisode n'aurait probablement pas pris la même

importance si la "pentalogie" avait été achevée.

La première

partie, littérairement la plus frappante, par sa structure et la sûreté

tranchante des remarques psychologiques, met en scène plusieurs groupes de

réfugiés de tous milieux. Les fils devaient se réunir dans le troisième tome,

Captivité. On voudrait citer d'innombrables scènes où se lisent la subtilité et

l'intransigeance des analyses de la romancière. Le lynchage d'un jeune prêtre

par les enfants qu'il a en charge et qui en éprouvent "un effroyable bonheur",

le vol de l'essence par un lâche qui abuse de la naïveté d'un jeune couple ou

encore les compromissions d'un homme de lettres médiocre.

L'art romanesque

d'Irène Némirovsky atteignait ici une précision que la fébrilité aurait pu

menacer. Comment est-elle parvenue à ce détachement cérébral sans détruire

l'émotion ? La "méthode indirecte" qu'elle utilise pour entrer dans la pensée

des personnages les plus négatifs et en révéler la bêtise flaubertienne ne nuit

jamais à la palette des nuances. Le trouble que suscite l'apparition des soldats

allemands, jamais rejetés dans le mal, la ténuité des convictions face à

l'ouragan des situations, l'égarement des individus projetés dans un "esprit

communautaire" qu'exige l'urgence politique : une femme seule, avec son

intelligence et sa science littéraire, traite admirablement ces thèmes que

l'horreur nazie va soudain balayer dans le néant.

Signalons aussi Destinées, nouvelles parues dans Gringoire et d'autres revues,

entre 1935 et 1941 (éd.

Sables, 15, route

de l'Eglise, 31130 Pin-Balma, tél. : 05-61-84-78-33, 284 p., 18 €).

An

invasion of German gents

(Filed: 13/12/2004)

George Walden reviews Suite Française by Irène Némirovsky

French fiction is far from its glorious peaks, but here is a prize-winning novel

that is making an international splash, and whose translation into English is

eagerly awaited. Significantly perhaps, the novel is not new; it was written in

occupied France in 1942, and only recently unearthed.

Its discovery is an extraordinary tale in itself. Irène Némirovsky was born in

Kiev in 1903, of Jewish parents. Escaping from Russia after the 1917 Revolution,

her well-to-do family settled in France, where she led a hedonistic life and

became a precocious literary success. The increasingly anti-Semitic atmosphere

led her to convert to Christianity in 1939, but it didn't help: when the Germans

invaded, she was listed as a foreigner and a Jew.

Hunted down by French gendarmes, she was handed to the Germans in 1942 and

slaughtered at Auschwitz. The gendarmes hunted her two young daughters as well,

but they escaped with a suitcase of family mementoes, including a manuscript

written in minuscule script to save on ink.

This was the two completed sections of the five-part novel their mother had

planned on the war, entitled Suite Française. "Tempest in June", the

first part, recounts the fall of France in 1940. Just as we see the shape of a

tree more clearly when its leaves fall, she writes in a bitter passage, so the

true nature of France was exposed by its total defeat. Her portrayal of the

cowardice and panic as the Germans approached is a devastating commentary on the

abject state of the country.

As all classes mingled in a desperate exodus from Paris, the trains and columns

of cars strafed by German aircraft, she follows the fate of a pampered bourgeois

family, a gutless aesthete, a good-time girl and a famous Parisian writer who

knows and cares nothing about his country. Not only are they temporarily

destitute, they are thrown into the company of the despised lower classes. Moral

squalor is the order of the day, and many arresting scenes include the murder of

a priest by the Parisian orphans he has led to safety.

But the squalor is general, and Némirovsky's picture of provincial life is

equally unromantic. The gentry come across as spiritual if not actual

collaborators, who privately believe that it was high time someone brought a bit

of order to France, while the peasants mostly emerge as ignorant, secretive,

sly, vengeful and avaricious, and not much of an improvement on their supposed

betters.

Stylistically there is nothing fancy about this novel – perhaps one of the

reasons for its success in France, whose literature can suffer from excessive,

reader-alienating sophistication. Yet nor is it a piece of conventional,

middlebrow writing, for all its melodramatic touches. Tolstoy's War and Peace

was on Némirovsky's mind as she wrote, for obvious reasons, and her prose has

both a narrative and intellectual solidity. The story is highly engaging, the

characters colourfully drawn, and the moral dilemmas faced by the French, as

well as the behaviour of the Germans, are cogently discussed.

The second part, "Dolce", describes the effect of the occupation on a small

town, and revolves around the (unconsummated) love affair of a German officer

and a Frenchwoman on whom he is billeted. The petty intrigues and profiteering

at all social levels are wonderfully described. It is too early for the

Resistance to feature, but it is noteworthy that only a single farmer, reputedly

the local communist, makes a gesture of defiance against the Germans.

More controversial than Némirovsky's picture of a rotten, demoralised country on

the eve of war – by now something of a commonplace – is her portrayal of the

Germans. Young and spirited, with their smart uniforms and superb horses, and

with manners that make the provincials look boorish, they are a long way from

brutal stereotypes. Cars, horses and lodgings are requisitioned, but no one is

killed; indeed the occupiers go out of their way to show themselves civilised.

The bookish and musically gifted Bruno, the central German character, refrains

from forcing himself on his French love. The conversations between them

summarise the plight of the individual versus the state in time of war, and the

message is that human beings, even Germans, cannot be arbitrarily categorised.

Bruno is simultaneously a sensitive fellow and a dutiful soldier, who utters the

infamous words "only obeying orders" long before they became a macabre joke.

And for today's readers, that is the tragic irony in this book. Its plot is

inextricable from Némirovsky's fate, even though she doesn't feature, and there

is nothing much about Jews in the novel. The question we are bound to ask is

brutal but inescapable: had she lived through the Holocaust and seen the full

extent of German savagery in France and other countries, would she have gone out

of her way to humanise individual Germans, as she does here?

For as we now know, not a few of the concentration camp personnel of the kind

who murdered this gifted writer listened to Beethoven in the evenings. How would

the piano-playing but none the less dutiful Bruno have behaved had he been

seconded to Auschwitz? I think I know. Hence the added poignancy of this

exceptionally powerful novel.

'Suite Française' by Irène Némirovsky will be published in English in late

2005/6 by Chatto & Windus.

Issue: 1 January

2005

General fiction from France . . .

Anita Brookner

On 30 August 2004 a woman wrote

a letter to Le Figaro registering her dismay at the number of novels scheduled

for publication in the three months that constitute the rentrée littéraire in

France each autumn. She confessed that, although an assiduous reader, she rarely

found anything of distinction in what was on offer and deplored the lack of true

literary worth, let alone devotion to the task in hand. She perceived that this

volume of production is little more than sheer economic activity.

This was a worthy and pertinent

comment, an alternative reading to the literary pages, in which reviewers are

often more complimentary than is entirely justified. It is certain that of the

many novels published this season few will merit genuine and serious attention.

There was, for example, little discussion of the award of the Prix Goncourt to

Laurent Gaudé for Le Soleil des Scorta, apart from the fact that it was

published by the relatively obscure Actes Sud. By the same token greater

interest surrounded the publishing fortunes of Irène Némirovsky’s Suite

Française which featured prominently at the Frankfurt Book Fair and has

attracted no less than 19 foreign bids for translation rights. Yet this is less

a novel than a voice from the past: that it has become a talking point is worthy

in itself, for the fearful fascination of Suite Française lies in its attempt to

come to terms with an endeavour so monstrous that few could contemplate it. The

very function of the novel was at stake here, for it laid bare both the writer’s

egotism and her despair at her inability to save even a single life.

It was awarded the Prix Renaudot.

Némirovsky had, as a young

woman, moved from the Ukraine to France, and grew up as French. All this changed

during the Nazi occupation when her Jewish origins, and those of her husband,

condemned them both to Auschwitz where they perished. Némirovsky had had some

success as a writer in Paris before the war and was working on the present book

when she was seized and deported. The book was transcribed from the papers she

left behind and edited by her surviving daughter Denise Epstein. It was finally

published by Denoël in 2004.

It is a disconcerting read, an

authentic chronicle of exile peopled by fictional characters reluctant to leave

their Parisian lives behind them. This forms the first part of the chronicle;

the second deals with the occupation and its effects. The tone is agreeable,

unemphatic, that of a society novel which rarely descends into raw emotion.

Rather more revealing are the notes that Némirovsky made for her own purposes

rather than for an audience. Here a bitterness is evident, but strangely a lack

of awareness of the fate that awaited Jews such as herself. Her main

preoccupation is the work in progress, which she intended to complete in three

more long sections. She writes that the personal lives of her characters should

have more weight in the novel than historical events, but her worldliness is

becoming fragmented. This is something of a relief, for that worldliness, that

blandness suddenly seems discordant, evidence of a desire to conform, to comply

which is not in itself particularly attractive. The irony is that her writing

was overtaken by history in a manner she was unwilling or unable to foresee. The

book thus achieves a tragic resonance, as does Denise Epstein’s desire to

illuminate her mother’s life and work.

Suite Française is fully

justified. It has been hailed as a masterpiece, which it may be, but for the

wrong reasons. It is rather an heroic attempt to write a novel about a nightmare

in which the writer is entirely embedded. It is thus an act of moral courage

beyond the norm, or perhaps the only method of retaining sanity in response to

unnatural dangers. And yet it is recognisable as a novel, even of manners, in

which the social classes are faithfully delineated. It arouses a certain unease

in the reader who has the benefit of hindsight. It is interesting to note that

Némir- ovsky’s earlier and largely forgotten novels have been reprinted and are

already in the bookshops.

The Prix Femina was awarded to

Jean-Paul Dubois for Une Vie Française (Editions de l’Olivier) which is less

ambiguous. Punctuated by presidencies from de Gaulle to Chirac, this is in

effect a rite of passage novel and at the same time an autobiographical

reflection on what it was like to be young, and then not so young, from 1958 to

the present day. This account of sexual awakening, of student revolt, or simply

revolt against the established order, matures into reluctant coming to terms

with professional achievements and domestic disappointments in the light of

middle age. Unashamedly personal, the novel slowly becomes weightier, until it

turns at last into the tragedy it was always intended to be. With his own

failures amplified by the events of 9/11 and the mysterious explosion in the

author’s own city of Toulouse which has never been properly explained, Une Vie

Française finally attains a simplicity and indeed a dignity which might satisfy

that correspondent who was moved to write to the newspaper complaining of a lack

of energy in what publishers had to offer readers like herself.

By contrast the Prix Médicis

was awarded to La Reine du Silence (Gallimard) by Marie Nimier which is all

languor and self-absorption. This is a mind-numbing investigation into the death

of Roger Nimier, the author’s father, in 1962. Roger Nimier, the picturesque

author of Le Hussard Bleu, had been driving in his Aston Martin with a woman

passenger when he crashed the car and died. Forty years later his daughter

embarked on a personal inquest into his death, visiting his tomb, interviewing

the woman passenger’s son, while at the same time cataloguing details of her own

life which are hardly relevant to her self-appointed task. It transpires that

Roger Nimier was a violent man who once put a gun to his infant son’s head, that

he let himself be photographed with writers and actors but never with his

children. His daughter, to judge from this account, suffers from this legacy,

which continues to haunt her. Limpidly written, this is nevertheless a morbid

undertaking, in which too few facts do duty for others which have been lost, and

even those few too inconsequential to satisfy the reader.

That there are too many novels

is a conviction widely held but rarely acknowledged. Some — too few — will be

good. Most will be diverting. Others will disappoint. Such, I fear, will be the

fate of Laurent Gaudé’s Prix Goncourt-winning Le Soleil des Scorta, an Italian

family saga written in a style much too melodramatic for its content, and thus

simultaneously old-fashioned and excessive. The brave woman who confided her

disappointment to Le Figaro was that humble creature, the common reader. We wish

her

well in her quest, and assure

her that her observations have been noted.

The TLS n.º

5311, Friday 14 January 2005

The road to Auschwitz

A novel saved from the flames

David Coward

SUITE FRANCAISE

Irène Némirovsky

434pp.

| Denoel. £22.

| 2 207 25645 6

Last autumn,

some 650 novels were published in France for the start of the new literary

season. Most will exhaust their average three months of shelf life and vanish

before finding a public. Such, however, is unlikely to be the fate of Irène

Némirovsky’s Suite française, which came out in France in September, sixty-two

years after it was written. It was greeted ecstatically by the French literary

press who called it “astounding”, “a symphony”, “a masterpiece”. It was duly

awarded a major literary prize, the Prix Renaudot, though not the Goncourt,

which by tradition is reserved for living writers. For Némirovsky died in 1942.

She was born in

Kiev in 1903 into an upwardly mobile middle-class Ukrainian

family. By 1914, her father, an energetic cap-italist, had become one of

Russia’s wealthiest bankers, and the family lived in great style. Holidays were

spent in the Crimea, at Biarritz and on the French Riviera, and on the eve of

the First World War they moved to St Petersburg. The more her Jewish husband

prospered, the more Fanny Némirovsky, who felt she had married beneath her,

distanced herself from his clan, and she turned into a vain, imperious grande

dame quite deficient in maternal feeling. Irène Némirovsky learned to hate her

mother and left bitter portraits of her in her novels, notably in Le Vin de la

solitude (1935). In her fiction, she also expressed considerable hostility to

Jews, whom she wrote about with a “fascinated horror”, as Myriam Anissimov

observes in her excellent biographical introduction to Suite française. However,

Némirovsky distinguished carefully between integrated French Jews, whose values

and destiny she shared, and those cosmopolitan men of business (like her father)

in whom “love of money had replaced all other sentiments”.

In 1918, in the

aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the family fled to Finland, where they

remained for a year before moving to Sweden, and thence to France, in 1919. By

now, Némirovsky spoke six languages in addition to the French she had learned

from her governess. She led a life of privilege in Paris, Nice and Biarritz –

elegant dinner parties, balls, receptions – at a time when France’s war heroes

were returning to a world of unemployment and deprivation. But she was also

devouring “decadents” like Huysmans and Wilde, whom she later abandoned for

realists such as Balzac, Turgenev and Maupassant. She took a degree in French

Literature at the Sorbonne and in 1923 began selling short stories to magazines

and periodicals. In 1926 she married Michel Epstein, a Russian émigré

businessman, and began a family. Denise, born in 1927, was followed ten years

later by Élisabeth.

Némirovsky made

her name with her second novel, David Golder (1929), the story of an ageing

Jewish financier tolerated by his wife, preyed on by his spendthrift daughter

and valued by both for his ability to supply them with luxury. It was translated

into English and German and the rights were bought by Julien Duvivier who turned

it into a film. In the decade that followed, she published a new title every

year or so and her work drew admiring notices from novelists as different as

Joseph Kessel, who was Jewish, and Robert Brasillach, an anti-Semite. Into a

carefully observed world of upper-middle-class cosmopolitan society, she

released hysterical women, volatile entrepreneurs, clever Jewish boys who are

destroyed by the patronage of the idle rich (L’Enfant génial, 1926) and

disturbed daughters, like Hélène of Le Vin de la solitude, who can begin her

life only when she has freed herself from hatred for her mother and her father’s

lucre, and can come to terms with the childhood which has almost destroyed her.

For many, salvation is achieved through renunciation of the crass materialism so

valued by the rest of the world.

Although

Némirovsky’s character studies and novels of manners might seem to echo the

psychological and social (though not the religious) concerns of François

Mauriac, she stood somewhat apart from the major trends of 1930s fiction. Her

cosmopolitanism was not the raffish and escapist kind popularized by Paul Morand

and Maurice Dekobra. She did not share the taste for action shown by Kessel,

André Malraux and Saint-Exupéry, nor was she interested in ideas, as were André

Gide or Georges Bernanos. What drew readers into her fictional world was her

human warmth, her emotional intensity and self-effacing manner. These were

traits she greatly admired in Chekhov, whose biography she wrote in 1940. It is

an elegy on the life, work and early death of a modest, unassuming, good man and

a writer of acute, understated sensibility. It is an assessment which also fits

Némirovsky.

Her writing

method was drawn from the traditions of French realism. A first draft laid out

the bare bones of the narrative which enabled her to know her characters, for

whom she compiled full dossiers on their past, personality, appearance and

education. Using these details and facts from careful background research (for

one character in Suite française she consulted a history of porcelain), she then

rewrote her original outline. This approach she learned from

Turgenev, but

it was from Flaubert that she borrowed the “indirect method” which meant

explaining nothing, masking the authorial voice and showing character and action

as active not reported drama. “The reader”, she noted in

English, “has only to see and hear.”

In February

1939, Némirovsky and her daughters were received into the Catholic Church. It

was a conversion prompted almost wholly by the deteriorating international

situation. On September 1, the children were taken to safety at Issy-l’Évêque, a

village in the Morvan. She and Michel stayed in Paris but visited them

regularly. A new novel appeared in 1940 and her Chekhov book and another novel

were completed but not published. The law of October 1940 which gave Jews

inferior legal status meant that Michel could not work and Irène could not

publish. A second law in June 1941 made them liable for deportation.

They moved to

Issy but made no attempt to flee the country. Slowly the net closed. On July 13,

1942, Irène was arrested by French gendarmes, taken to a camp at Pithiviers and

sent to Auschwitz four days later; she died on August 17. Michel made frantic

efforts to discover her fate, but he in turn was arrested in November and sent

to Auschwitz where he was gassed on arrival. Their two girls were saved by the

village schoolmistress who smuggled them to Bordeaux, where they hid in cellars

and survived the war. In their hurry to flee, they took the notebook that had

seemed so important to their mother. It contained “Suite française”, the first

two parts of a projected sequence of five novels set in wartime France.

The first,

“Tempête en juin”, is a montage of sharply focused snapshots of the great exodus

from Paris after the first bombs fell on June 3, 1940. Parisians fled the

capital by train, car and lorry and, when the stations closed and the petrol ran

out, on foot. Among the crowd, we make out the Péricand family whose confusion

expresses the horrified realization that France has been defeated. Monsieur will

stay at his post, and his eldest son, Abbé Philippe, will evacuate a squad of

orphans. Madame will take the children to safety in the Midi. Hubert, aged

eighteen, burns to fight the Hun, Grandpère is not sure what time of day it is,

and the eight-year-old twins enjoy every moment. We meet Gabriel Corte, popular

novelist and successful playwright, who is accompanied by his mistress and

driven by his chauffeur, and Charles Langelet, a wealthy aesthete who rates

beauty higher than people and worries less about the fate of France than about

his collection of antique china.

The

working-class occupants of a battered car who so offend Corte’s sensibilities

survive better than the bourgeois who are lost in this new world where there are

no servants and they must fend for themselves. But Corbin, the banker, like his

mistress, Arlette, who has a heart like a bag of knuckles, does well. Abusing

his position, he bullies the Michauds, a conscientious, middle-aged couple who

work for him. They have a son, Jean-Marie, at the Front. They are the only

decent people in sight.

Némirovsky’s

graphic mosaic of the débâcle is highly critical of the French. They had grown

tired of the Republic, she notes, as a man tires of a spouse, and had flirted

with dictatorship. But they had wanted only to deceive their wife, not kill her,

and now she was dead and they had lost their freedom. Némirovsky proceeds to

spell out what this means. By the time the Armistice is declared on June 22, Mme

Péricand has lost Philippe (murdered), Hubert (missing) and Grandpère (mislaid).

Corte’s comfortable world has gone and he is bereft. Langelet is killed by a car

driven by Arlette, who is set to have a good war, as will Corbin, who sacks the

Michauds and leaves them to face an uncertain future and their worries about

Jean-Marie.

Némirovsky’s

stance is unforgiving and her portrait of human nature in a crisis is damning.

Few, and certainly not the well-to-do, emerge with any credit. There is also a

distinct sound of scores being settled with the smug bankers and the complacent

bourgeois who include the publishers who dropped her and her kind. Yet she never

quite loses a kind of amused detachment which supplies not only satire (Corte in

search of a meal, young Hubert in search of a battle, like Fabrice in Stendhal’s

Chartreuse de Parme) but also unexpected humour, which runs from low farce to

black comedy: there is more than a whiff of Evelyn Waugh in the fate of Abbé

Philippe. Yet Némirovsky’s faith in human nature remains intact, and Part One

ends with the valiant Louise (three children, husband a POW) looking out at the

March countryside as spring 1940 returns.

Part Two,

“Dolce”, is set a few miles from Louise’s farm at Bussy, a village in Central

France which is occupied by the Germans who have been thus far only a distant,

disembodied threat. We follow the interwoven fortunes of a smaller and largely

fresh cast of characters who illustrate a natural history of collaboration:

propinquity begets familiarity which begets fraternization which begets a black

market and denunciation. The centre is occupied by Lucile, an unloved wife, who

becomes progressively infatuated with Bruno, a cultured, civilized officer who

is cousin to the “good” German of Vercors’s Le Silence de la mer (1942), that

clear-eyed reminder that humanity can exist in wartime too. But others react

differently. Benoît fights back because he is a man’s man and a Communist, his

wife, Madeleine, because it is right so to do, and snobbish Mme Angellier

because she is exhilarated by her visceral xenophobia. It takes the villagers

three months to move from defeat and occupation to full-blown collaboration and

the beginnings of Resistance.

What would have

happened next is hinted at in the brief notes which are set out in an appendix

to this volume. Bruno would die on the Russian front, Benoît would be shot,

Jean-Marie Michaud would return, love Lucile and resist. But the exact shape of

the narrative would have to wait on events. Whatever happened, however, the saga

would continue to test the balance between the “community spirit”, which meant

both collaboration and resistance, and the “individual spirit”, which meant

retaining that “inner freedom” felt by M Michaud and Benoît. For Némirovsky, it

was an existential not a philosophical issue, for the will is forever

compromised by circumstances. Lucile is determined to be free. Yet by hiding the

Resistance member Benoît, she knows she has made her choice.

“Dolce”, a mix

of delicate observation, amused tolerance and bitter satire, confirms the

promise of “Tempête en juin”. The completed five-segment sequence was to have

the rhythm of a Beethoven symphony or perhaps a film. How this would have worked

is now impossible to assess. But what has survived of Némirovsky’s mini roman

fleuve, painstakingly transcribed by her daughter Denise, is a uniquely resonant

picture of France defeated and occupied, a book of exceptional literary quality.

It has great delicacy of feeling, marvellously varied humour, a lyrical

appreciation of nature, and a style which ranges from the slyly ironic to the

Proustian period. Many admirable autobiographies and novels about that dark time

have appeared since 1945. But they all start with the knowledge of how it all

ended. Suite française is not mediated by hindsight, nor does it use any of the

props which would later become standard in Resistance fiction: air-drops,

bridges blown, trains sabotaged and the like. Némirovsky’s drama of the Exodus

and the Occupation is low-key and human in scale and it has the kind of

immediacy found in the diary of Anne Frank.

Denise and

Élisabeth did not share the tragic fate of their mother. After the Liberation,

they travelled to Nice, where their grandmother had spent the war in some

comfort. She refused to see them. Through the door she told them that since they

were orphans they had best take themselves off to an orphanage. There is nothing

in these pages to indicate that Mme Némirovsky mère ever made amends. It is

recorded, however, that she died in one of the more comfortable quartiers of

Paris in 1989 at the age of 102. It is unlikely that even Irène Némirovsky,

mistress of the “ironic contrast”, could have invented a circumstance more

poignant.

Portrait

Denise Epstein, 74 ans, fille d'Irène

Némirovsky, écrivaine à succès déportée à Auschwitz. Elle fait publier l'ultime

texte de la disparue, un roman inachevé sur la débâcle de 1940.

Le

livre de ma mère

Par Pascale NIVELLE

vendredi 29 octobre 2004

Denise

Epstein en 8 dates

9 novembre 1929

Naissance à Paris.

17 août 1942

Assassinat d'Irène Némirovsky à Auschwitz.

6 novembre 1942

Assassinat de Michel Epstein à Auschwitz.

1953

Mariage.

1954

Naissance de son premier fils.

1962

Documentaliste.

1996

Mort de sa soeur Elisabeth Gille.

Septembre 2004

Publication de Suite française d'Irène Némirovsky

(Denoël).

Comment dire...

Fardeau, malheur, destin ? Non. Denise Epstein n'est pas une victime. Elle

cherche le mot qui raconte tant d'années ralenties, à regarder passer la vie

sans pouvoir tout à fait y croire. «Cailloux ! J'ai fait cadeau de mes

cailloux.» Elle sourit, petite fille camouflée sous un treillis de rides :

«Je traverse une période heureuse. Je n'ai plus de poids sur les épaules. Ça

ne m'était pas arrivé depuis plus de soixante ans.» Ses souvenirs de bonheur

s'arrêtaient au 13 juillet 1942. Avant que sa mère, Irène Némirovsky, ne

disparaisse entre deux policiers français. Irène avait 39 ans, Denise 13. Après,

la joie a toujours semblé teintée de gris.

Au printemps

dernier, Olivier Rubinstein, éditeur chez Denoël, a reçu une lourde enveloppe

postée à Toulouse. Le caillou de Denise, un roman inédit d'Irène Némirovsky sur

l'exode et les premières années d'occupation. Il a d'abord douté. L'histoire de

ce manuscrit inachevé d'un auteur célèbre, sauvé par une fillette pendant la

guerre et couvé toute une vie, était trop belle. D'autant que la soeur de

Denise, Elisabeth Gille, longtemps éditrice chez Denoël et morte en 1996, n'en

avait jamais parlé. Puis il a lu, «j'ai rarement été bouleversé à ce point»,

et a rencontré Denise Epstein, toute en modestie. Depuis, Rubinstein vit un rêve

d'éditeur. Succès en librairie et mise aux enchères à la Foire de Francfort :

«Le monde entier débarque pour acheter Suite française. Je n'ai jamais

vécu une aventure pareille !» Denise, qui enchaîne les interviews, non plus.

C'est Myriam Anissimov, auteur d'une biographie sur Romain Gary, qui a joué les

passeuses. Quand Denise, au hasard d'une signature dans une librairie

toulousaine, a évoqué le roman d'Irène, idole de Romain Gary, Myriam a bondi sur

son portable : «Denise ne voulait pas publier un roman inachevé. Elle était

persuadée que sa mère ne l'aurait pas voulu. J'ai été obligée de prendre le

pouvoir.» Six mois plus tard, Denise Epstein n'a plus de scrupules : «Ma

mère et ma soeur doivent trépigner d'excitation, je ne sais pas où, là-haut»

Elle apprend la légèreté : «Longtemps je me suis demandé pourquoi j'avais

survécu. C'était pour ça.»

Son plus gros

caillou, qui en retenait beaucoup d'autres, était ce manuscrit, un épais

classeur de maroquin gravé des initiales I.N. Après l'arrestation d'Irène, qui

ne s'en séparait jamais, il trône dans la maison d'Issy-Lévêque, dans le Morvan

où la famille est réfugiée. Ce sont de grands bourgeois russes, héritiers de

banquiers, qui ont fui les bolcheviks en 1917. Depuis juin 1940, il est interdit

à la mère de publier et au père d'exercer son métier, courtier dans une grande

banque parisienne. Juifs, étrangers, ils sont les premiers menacés et ne le

savent pas, persuadés que les nazis ne s'en prendront pas à leur monde, que les

relations d'Irène les protégeront.

Ils auraient pu

émigrer aux Etats-Unis et ne l'ont pas fait. Pas plus qu'ils n'ont franchi la

ligne de démarcation. Ils attendent la fin de l'orage. Irène noircit son

classeur d'un roman ambitieux, son Guerre et Paix d'un autre siècle. En

juillet, elle est arrêtée. Michel Epstein est désespéré, il écrit à la

préfecture : «Laissez-moi partir à sa place.» La réponse de Vichy arrive

en octobre, deux gendarmes l'arrêtent avec ses filles de 6 et 13 ans. Mais les

nazis ne déportent pas encore les enfants. Un officier allemand fait comprendre

qu'il faut fuir. Michel part seul. A sa fille aînée, il confie le dernier trésor

de famille : quelques bijoux, des photos et le gros cahier. Denise, qui passera

trois ans cachée dans un couvent puis dans des caves de la région bordelaise, ne

s'en séparera qu'à la fin de la guerre. Elle traîne la valise de cache en cache,

le manuscrit lui sert d'oreiller. A la Libération, les soeurs guettent les

trains de revenants sur les quais de gare. Ni parents, ni oncles, ni cousins, la

famille est décimée. Reste une richissime grand-mère, revenue dans son

appartement proche de l'Etoile après guerre. Qui ferme sa porte et les

déshérite. «Il arrive, c'est rare, de rencontrer des gens sans coeur»,

explique Denise, encore amusée de l'enterrement de Fanny Némirovsky, 102 ans.

«Ses robes de soirée occupaient dix mètres de penderie, on a appelé un

brocanteur. Puis on a invité les chauffeurs de taxi à faire un bon gueuleton.»

Sans Albin Michel, fidèle éditeur d'Irène, qui organise une souscription dès

1945, c'était l'assistance publique. Denise est placée dans un pensionnat

catholique huppé de la région parisienne, Elisabeth est accueillie par une

famille de la bourgeoisie. Le manuscrit part chez un notaire. A 20 ans, Denise

essaie de vivre : «Quand on sort de tout ça, on fait plutôt semblant.»

Denise se marie

avec un économiste. Elle a récupéré le manuscrit, l'a rangé dans les étagères de

sa bibliothèque «comme une relique», ne peut pas l'ouvrir. Elle lit

beaucoup, s'occupe de ses trois enfants, milite. Au PSU, puis à la LCR, toujours

à gauche, dans des associations laïques, «du côté des malheureux, des

immigrés». Elle vit en banlieue parisienne, avec quelques excursions à

Saint-Germain-des-Prés où sa soeur fait carrière dans l'édition. Une vie

modeste, mère et militante, documentaliste sur le tard à la répression des

fraudes. Quand Elisabeth, revenue aux sources de sa communauté, entreprend une

biographie imaginaire de leur mère (1), Denise l'aide et s'efface. «Elisabeth

était incisive, coupante, elle avait une forte personnalité. Denise a toujours

été modeste», explique Myriam Anissimov. «Ma soeur avait d'abord

construit un mur de béton autour de son histoire, puis elle l'a ouvert,

raconte Denise. Moi, je me sens autant juive que musulmane, je n'aime pas les

catégories. Surtout maintenant, si on dit qu'on est contre la politique de

Sharon et qu'on n'est pas religieux, on est vite traité de mauvais juif et de

traître.» Avec le recul, elle dit : «Je ne me suis pas trompée. Je n'ai

pas été communiste, ni pour la violence. Mais comme beaucoup de gens de gauche,

je me rends compte que j'ai surtout rêvé de choses qui ne sont pas arrivées.»

Après la mort

d'Elisabeth, le classeur est toujours là, intact et pratiquement illisible, tant

le papier de l'Occupation est mauvais et l'écriture minuscule. «Je l'ai

ouvert, refermé, ouvert, refermé. C'était terrible, cette présence, cette vie à

l'intérieur.» Un jour, Denise décide de confier le manuscrit à l'Imec

(Institut mémoire de l'édition contemporaine). Mais, avant, pour ses enfants,

elle veut le déchiffrer et garder une copie. Un travail à la loupe, beaucoup de

larmes d'émotion et de fatigue pendant plus de deux ans. Une copie est partie

chez Denoël en avril, lourde d'espoirs et de remords. Ce caillou, elle l'a semé

à son tour. «Je commence à me rendre compte que je vais avoir une autre idée

de moi-même. Moi qui ai passé ma vie à me dire que je n'étais pas importante.»

Il arrive qu'on naisse à 75 ans.

More war than

peace

Sixty

years on, Irène Némirovsky's unfinished masterpiece finally sees the light of

day. Helen Dunmore salutes Suite Française

Saturday March

4, 2006

The Guardian

Suite Française

by Irène Némirovsky, translated by Sandra Smith

403pp, Chatto & Windus, £16.99

On July 11 1942

Irène Némirovsky wrote in her notebook: "The pine trees all around me. I am

sitting on my blue cardigan in the middle of an ocean of leaves, wet and rotting

from last night's storm, as if I were on a raft, my legs rucked under me! In my

bag, I have put Volume II of Anna Karenina, the diary of KM and an orange. My

friends the bumblebees, delightful insects, seem pleased with themselves and

their buzzing is profound and grave. I like low, serious tones on voices and in

nature ... In a moment or so I will try to find the hidden lake."

It was

Némirovsky's habit to go into the woods to write, and to make notes on her

work-in-progress. This was to be a novel written in five sections, dealing with

France under German occupation. The book, she thought, would be a thousand pages

long: an ironic reference to the German fantasy of a thousand-year Reich. She

completed the first two sections, "Storm in June" and "Dolce", and together

these make the novel now published as Suite Française. Even these sections were

not finished, in Némirovsky's view. She intended to revise, noting that the

death of one character was perhaps schmaltzy, and that she found "in general,

not enough simplicity".

Like Katherine

Mansfield, whose journal she took to the woods on that July day, Némirovsky was

an incisive critic of her own work. This search for simplicity reflects

Mansfield's own longing to purge her work of effective little writerly tricks.

Némirovsky knew what she was aiming for, how high a standard she had set for

herself, and how hard it would be to achieve.

Her model for

this large-scale novel set in wartime was Tolstoy's War and Peace, which she

knew intimately. There is a great deal of play and echo between War and Peace

and Suite Française, some of it respectful, some experimental. Némirovsky

creates brilliant and often ironic parallels between scenes in the two novels.

For example, Tolstoy's description of the Rostov family loading their

possessions into carts as they prepare to flee Moscow before Napoleon's advance

is echoed in a scene in Suite Française where the wealthy, bourgeois Péricand

family crams its worldly goods into the car as the Germans advance on Paris. But

while Natasha Rostova is horrified by her family's materialism, and shames them

into emptying the carts and filling them with wounded soldiers, the Péricands

behave throughout with selfishness barely cloaked by convention. Their departure

is absurd, and it is observed with cool, merciless comedy. The high-minded,

religiose Péricands delay not because they wish to help anybody else, but

because the monogrammed linen is not yet back from the laundry. Némirovsky

understood very well the callousness of those who consider themselves virtuous.

Unlike the Rostovs, the Péricands cannot be abashed, and cannot repent.

In her

increasing isolation and danger, Némirovsky had good reason to understand the

psychology of collaboration. Her portrait of French society in the tumult of war

and occupation is not judgmental, but it is devastating. The Michauds, clerks

who belong neither to the bourgeoisie nor to the working class, are almost alone

in their kindness, their gentle, practical goodness and their realism about

human suffering. This couple resembles the wise innocents so cherished by both

Tolstoy and Dostoevky, who become touchstones for those around them without

making the slightest claims to moral grandeur.

Tolstoy's

technique fascinated and inspired Némirovsky, as her notes on the composition of

Suite Française show. Némirovsky had been forced to leave Russia at the age of

15, after the revolution, and French became her everyday language as well as the

language in which she wrote. But her work does not repudiate her Russian

identity: instead it reflects the historical interplay of the French and Russian

languages in Russian literary culture. Némirovsky comes across as an intensely

Russian writer, lyrical, forceful, earthy, idealistic and yet without illusions.

The influence

of Turgenev and Chekhov is also apparent. Her descriptions of the French rural

landscape have the blend of realism and poetic tenderness that Turgenev

perfected in Sketches From a Hunter's Album. Like Chekhov, she observes and

powerfully expresses the detail that fixes a scene, whether interior or

exterior. For example, when the injured soldier Jean-Marie Michaud is sheltered

by a farming family in a remote hamlet, a girl puts a bunch of cherries next to

him on the pillow. Jean-Marie is delirious and has returned to a childlike state

as he slips in and out of consciousness. But all the time he's aware of the

cherries. "He was not allowed to eat them, but he pressed them against his

burning cheeks and felt content and almost happy."

When she began

Suite Française, Némirovsky was in her late 30s and already a well-known

novelist. From her notes, it's clear that she knew her new work was of a

different order. "Today, 24th April, a little calm for the first time in a very

long time, convince yourself that the sequences in Storm, if I may say so, must

be, are a masterpiece. Work on it tirelessly." Her longing to complete the

masterpiece which she believed she had in her is immensely moving, given that

she was never able to go beyond the second section of the novel. Two days after

Némirovsky sat writing for the last time in the Maie woods, she was arrested by

the French police under a directive that affected "stateless Jews between the

ages of 16 and 45". She was taken first to Pithiviers concentration camp, and

from there was deported to Auschwitz, where she died on August 17 1942. Her

husband, Michael Epstein, had begged for her release but was also arrested and

sent to the gas chamber immediately after he arrived at Auschwitz on November 6.

Her children escaped death only because of the dedication of their carers.

The manuscript

of Suite Française was preserved by Denise Epstein, Némirovsky's daughter, who

was 12 at the time of her parents' murder. She kept her mother's leather-bound

notebook with her each time she and her younger sister were moved from one place

of safety to another. Almost 60 years later, Denise read the notebook and

discovered that it contained not a diary, as she had always supposed, but a

novel. The history of the manuscript, and its survival, is remarkable enough.

The authority of the novel, though, does not come from its history, but from its

quality. Incomplete as it is, lacking the revision that its author undoubtedly

wished to give it, the narrative is eloquent and glowing with life. Its tone

reflects a deep understanding of human behaviour under pressure and a hard-won,

often ironic composure in the face of violation.

Némirovsky

understood that her own life was about to be horribly violated, even though she

could not know exactly what was intended for France's Jews. She created

characters who would coexist comfortably with these violations, such as the

author Corte, a man of letters whose preciousness about his own creativity is

matched only by his mean-spiritedness. Némirovsky noted that "Corte is one of

those writers whose usefulness will become glaringly obvious in the years

following the defeat; he has no equal when it comes to finding euphemisms to

guard against disagreeable realities".

In the

fictional world of Suite Française, everything is in flux. Some are stunned,

while others already jockey for position in the new order. A few prepare

themselves to resist. But nothing is abstract; everything is made present,

whether it's the cherries on the pillow, the privileged little dinner that Corte

secures for himself and which is then snatched away by a hungry man, or the

sound of music drifting over a lake at evening while young German soldiers

celebrate. Perhaps Némirovsky's most extraordinary achievement is the humanity

of these individual Germans, and the sense of tragedy when their celebration

dissolves at the news that Germany has invaded the Soviet Union. Their dreams of

peace vanish; fantasies of a bargain between conquerors and conquered cannot

survive.

Némirovsky's

pity for the German soldiers who will become fodder for this fatal campaign

gives grain and depth to these passages and suggests that her finished book

might indeed have been the masterpiece she hoped to create. Her days of writing

in the Maie woods were brutally cut short, but even in its incomplete form Suite

Française is one of those rare books that demands to be read.

Helen Dunmore's

House of Orphans is published by Penguin

More on the English

translation,

here

U.S.A edition,

here

Über die Deutsche übersetzung,

hier