|

|

16-9-2002

INICIAÇÃO SEXUAL

|

Kids'

Sexuality Finds a Champion—and Conservatives Attack

Underage and Under Siege

by

Sharon Lerner

Week

of

July 3 - 9, 2002

|

Ask Judith Levine when a kid ought to start having sex, and she'll respond like the levelheaded, Brooklyn- and Vermont-based liberal she is: "There are some 16-year-olds who can handle it, and there are some who aren't ready for sex at 20," said Levine, reached on the San Francisco leg of what turned out to be a profoundly embattled book tour. "People at 13 and 14 are generally not mature enough to carry out safe sex. And if a 10-year-old is engaging in what you or I might call real sex, that's a real problem." Utterly reasonable stuff. But read the ongoing press coverage of Levine's new book, Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex, and the public intellectual somehow morphs into a crazed pedophile. The madness began before Levine's book was even published. Arguing for recognition of young people's sexual pleasure, Harmful to Minors was rejected by a string of publishers (one dubbed it "radioactive") before being picked up by the University of Minnesota Press. Various outraged Minnesotans then demanded that the academic publisher stop printing the book (it hasn't) and begin a review of its editorial policies (that's under way). The ultra-right Concerned Women for America decreed Harmful to Minors an "evil tome." And Dr. Laura, the fang-toothed radio conservative, went on air to accuse Levine of condoning child molestation. |

|

The New York Times explained the witch-hunting of Levine by her book's release in the midst of the Catholic Church's explosive sexual abuse scandal. From a publicist's perspective, at least, the timing has been a boon; Levine's footnoted, scholarly work made it up to No. 25 on the Amazon.com bestseller list and has just gone into a 20,000-copy second printing. But what's so frustrating about the hysteria (aside from giving groups like the conservative Family Institute an excuse to host press conferences with lurid titles like "Pedophilia Book") is that it obscures Levine's astute analysis of what's gone wrong between adults and children in the U.S.

Drawing on social science and history, Levine makes a strong case that the denial of sexuality is the true cause of harm to minors. The book uses most of its 300 pages to detail the mounting anxiety over sex play between children, the restriction of youth access to the Internet, and a blackout on critical sexual information in the name of government-funded abstinence education. But Levine might just as well have focused on abusive priests. "If I wanted to design a historically accurate, long-term study to prove the point of my book, [the subject] would be the Catholic Church," the author sighed wearily across the phone lines from California.

Indeed the same prudishness that has backfired wildly in parishes across the country has dominated social policy in recent years. Harmful to Minors' most important contribution is tying that protective impulse to adults' deep-rooted discomfort with their own sexuality. In the section that secured her a central spot on the right's radar, Levine teases apart the disproportionately large spot the pedophile occupies in the American psyche. She doesn't deny that strangers sometimes rape children ("I can't believe I've had to clarify that," said the exasperated author), but points out that such crimes are far more often committed by family members. Levine describes the obsession with pedophiles as stemming both from a reluctance to confront incest and the rampant sexualization of children throughout the culture. Rather than focus on ourselves, she says, adults "project that eroticized desire outward, creating a monster to hate, hunt down, and punish."

For this intellectual take on such primal stuff, Levine has been branded a member of the "media elite"—and the charge of hyper-intellectualization contains a nugget of truth. Hers is an academic take on an issue about which few are willing to be totally rational. And while her criticisms of statutory-rape laws, say, are astute (she points out that age-of-consent laws originated to protect girls' virginity as their fathers' property and now define sex as nonconsensual solely on the basis of age), her own sexy camp tale, told this week in the Voice, is worth several such tightly reasoned analyses. "Jake," the 26-year-old embodiment of the gray areas in sexual relations, photographed a 14-year-old Levine with her shirt off. As she tells it, the experience was thoroughly enjoyable, though today such an encounter has been made all but impossible by the panic over sexual predators.

Talk to three female friends and you're bound to turn up at least one story of getting bedroom eyes and back rubs from the camp counselor (or friend's older brother, or windsurfing instructor, etc.). The problem is, it's almost as easy to hit upon the version in which the older guy doesn't refrain from sex with his camper (or student, or the baby-sitter). And often these stories have fairly messy endings. Levine's lack of sensitivity for the real problems—from crushed emotions to pregnancies —wrought by these relationships is partly to blame for the frenzied response to her book. Similarly, the book's vagueness about age—a fuzziness that could have been cleared up with a few clear statements like the one at the top of this piece—leaves unnecessary room for panic. And, since she never approvingly writes about young children having sex, she could have just as easily used the less provocative words teen or adolescent instead of child in the subtitle.

Levine does write about young children's sexual pleasure through masturbation and touch, though, defending the exploration of their bodies as natural and—gasp!—good. Perhaps the saddest chapter details how adult discomfort with children's sex play has, in some cases, turned kids' curiosity into pathology and crime, with hundreds of juvenile sex offender programs springing up to accommodate this new "epidemic." Levine tells of Tony Diamond, an unfortunate nine-year-old who was diagnosed with a sexual behavior problem and made to live in a foster home after touching his younger sister's genitals and poking her butt cheek with a pencil. Other kids caught up in the punitive mania include a 13-year-old boy accused of rubbing against his sister, and an eight-year-old girl who sent a note to a classmate asking if he wanted to be her boyfriend.

Even progressives have been cowed by this conflation of sexual expression and abuse—and Levine is as hard on them as she is on the religious zealots. She chews out sex educators for adopting new blend-in-with-the-conservatives names for their curricula like "abstinence plus" and "abstinence-based." She criticizes the nonprofit Sexual Information and Education Council of the U.S.—a frequent target of the right—for recommending that parents intervene if they stumble on their five-year-old consensually touching his friend's penis. (Better just to have "no reaction at all.") Even Planned Parenthood has apparently been running scared. Levine says the group's pamphlet "Birth Control Choices for Teens" originally contained a list of "outercourse" options, including reading erotica, fantasizing, and role play. But the racy suggestions were later deleted, and while the sanitized version was distributed, according to Levine, the contraband copies were burned.

Levine has a vision for swinging the pendulum back in the other direction. Adults are central to this plan, both because children eventually grow up and because the shame and secrecy about their sexuality start with adults' feelings about their own bodies and pleasure. Levine would have adults first reckon with their own desire. It's more utterly reasonable advice; were the tortured Catholic Church ever to take it to heart, it could be downright cathartic.

That's not likely, of course. With the possible exception of a few incendiary bits, Harmful to Minors will probably go unread by those who could benefit from it most. The missed opportunity brings to mind the image of those sex ed pamphlets burning in a warehouse somewhere, with so much hard work and daring effort being lost to the fiery shame around sex.

X-Rated Advice About Kids

and Sex

Parents Balk at Author's View That Minors Are

at Age of Consent

By Laura Sessions

Stepp

Washington Post Staff Writer

Saturday, May 11, 2002; Page C01

Once again: a provocative new book about child-raising that seems to be written for everyone except ordinary people who are actually raising children.

"Will the real sex educators please stand up? Mom and Dad aren't talking," writes New York feminist Judith Levine in her new book: "Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex."

She attacks right-wing anxiety over pedophilia, pornography and child molestation -- anxiety that is unwarranted by the facts, she says.

She denounces mainstream authorities for spreading hysteria by focusing on disease and pregnancy rather than children's rights to sexual pleasure and privacy.

She recommends looking at Dutch law, which allows children ages 12 to 16 to have sex with an adult if the young person is willing.

"Sex is not ipso facto harmful to minors," Levine writes, "and America's drive to protect kids from sex is protecting them from nothing. Adults owe children not only protection and a schooling in safety but also the entitlement to pleasure."

That is, the adults who teach the sex education courses Levine likes, but not necessarily parents, who don't count for much.

"Laudable protective parental instincts notwithstanding, an intimate consensual sexual relationship, including one between minors, is private business," she states.

Ingrid and Erick Gutierrez, natives of Guatemala living in a row house on Euclid Street NW, might be surprised to be told that they're not talking to their 13-year-old daughter.

Erick directs housing programs for the Latino Economic Development Corporation. Ingrid works with parents of students at Oyster Elementary School. They don't spend a lot of time debating the laws Levine gets worked up over, such as the Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation Act. They have other concerns to talk over with their daughter, simpler perhaps but no less pressing: rumors that a classmate is pregnant, or their daughter's question about why women have to suffer through monthly menstrual cycles and men do not.

"We're going to have to learn the right terms, and confront things before they happen," says Erick, sitting next to Ingrid at their dining room table.

They say it's up to them and not childless theorists like Levine to talk to their child about how one can give and receive sexual pleasure short of intercourse, and to discuss whether oral sex is safer than vaginal sex. They feel it's their private business to help their child think through when she might be ready for intercourse and the role that love and commitment should play in that decision. If their child is uncomfortable with them talking about these issues, they've already thought of a relative who can step in.

Citing research that asked adults about childhood romances they had years earlier, Levine argues for lowering the age of consent. What she doesn't say in the book, but has said in interviews, is that she had a sexual relationship with an older man when she was 17, unknown to her parents.

It's hard to picture Erick and Ingrid Gutierrez sitting back and doing nothing if their daughter, a pretty, dark-haired girl just easing into maturity, took up with a guy who was 19 or 20. Or 30.

"These are not informed-consent situations, where the child has all available information," health professional Sarah Brown says. "It's not like saying, 'Here, sign up for this appendectomy.' " Brown is executive director of the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, one of the mainstream organizations Levine says promotes fear of sex over pleasure.

Sharon Parker, who lives in an Olney colonial with husband Chuck, a car dealer, and four sons, ages 12 to 26, worries more about girls pursuing her boys than her twenty-something sons hopping in bed with teenyboppers. "These days, the girls are the aggressors," she says, "and I've told my sons that. Especially as girls get older, they can be very deceiving. They'll say they're using birth control when they're not."

Levine suggests that popular culture -- TV, movies, street talk -- is no trashier than it ever has been, but Parker says she has missed the real messenger. The culture Parker worries about is more neighbors down the street than "Sex and the City." It's the mother she knows who purchased birth control pills for her 13-year-old daughters "just in case." It's the parents who provide beer at parties in their homes and then let everyone, boys and girls, sleep over.

Her 14-year-old son is already asking to go to these sleepovers. She has said no.

Parker, in her mid-forties, remembers as a girl calling her mother at a party the evening she started menstruating and asking where she could find "those things women need." She got married when she was 18, had her first child at 23 and was "still clueless about sex" when she went into labor.

"I don't want my sons to be in that dark," she says. That is why she, like the Gutierrezes, is grateful that schools now teach youngsters about sex.

When Ingrid Gutierrez was her daughter's age, she was still wearing knee socks and playing with dolls. What little bit she learned about sex came in a vocational training class over a couple of weeks when she was 15. Erick Gutierrez picked up information at age 12 outside a bordello in his home town, listening to same-age friends recount their exploits inside.

Ingrid Gutierrez shakes her head and laughs, remembering the time her child came home bragging that she had gotten an A on her "gonorrhea test."

"In my time, that word was taboo," she says, "but I'm glad that they're teaching her about disease." Ingrid says the school gave her and her husband an approach for talking about sex that was scientific and therefore easier to manage.

Their point is, sex education in school, as comprehensive and necessary as Levine and many others believe it is, doesn't and shouldn't reduce parents to also-rans.

Parents must be partners with school for sex education to really work, and when they are, the results are rewarding, says Baltimore educator Deborah Roffman, author of "Sex and Sensibility: The Thinking Parent's Guide to Talking Sense About Sex."

Sharon Parker agrees. She remembers one of her sons assuring her that he was preparing for his sex-education test in sixth grade. Each afternoon she would ask him what he had learned and each afternoon he would say only, "Mom, I'm okay."

He flunked the test. So she marched over to the school office, retrieved the packet of material, and drilled him every afternoon during spring break.

At his first smirk during their first session, she stopped mid-sentence. "Okay, we're going to be mature about this," she said. "We're not going to call the male organ your ding-dong. We're going to use the word penis."

Now she recalls, "Even as I was saying that I was thinking, 'Oh my God, I can't believe I'm saying this.' I had to take a deep breath, several times, that first afternoon."

Her son took the test over and scored 98 out of 100. More importantly, she says, he realized he could talk to her about sex and she knew she could talk to him, even if she stumbled now and then.

The details of her instruction to her sons has obviously changed as they've gotten older, Parker says. She has told her boys she hopes they wait until marriage to have sex, but she has also counseled them on using protection.

Parents are in the business of deciding what is good for their kids, she says. They shouldn't be encouraged to abandon the job to schools, much less theorists, ideologues, provocateurs, shocking authors or even soothing ones. The Parkers, the Gutierrezes, on and on -- these are the actual people who have to deal with the blizzard of ideas that drifts down from intellectuals and politicians. They're the parents, after all, and their children are their children.

|

The

Romance a Teenage Camper Couldn't Have Today

Summer of Love

by

Judith Levine

Week

of

July 3 - 9, 2002

|

This is an innocent story. In 1967, the summer before my 15th birthday, I fell in love. It was my first intense erotic love, and its object was the photography counselor at camp—a lean, bearded, blue-eyed guy I'll call Jake. He was 26. Nothing sexual happened. Still, I think of those two months as the summer of my épanouissement, a French word meaning blossoming or opening, which also means glow. Jake took hundreds of pictures of me, and his affirmation and his camera opened me to myself. They helped me begin, sexually, to glow. If the same events had occurred in 2002, they would not be viewed as innocent. The adults around me would write my chaste romance as a perverse tale, casting Jake as a predator and me as his hapless, clueless prey. Had I started my sex education with good-touch-bad-touch lessons in kindergarten or listened for a decade to media reporting on a world allegedly crowded with sexual malefactors sniffing the world for young flesh, I might even have believed that my friend and mentor Jake was one of them. That sweet idyll would have been, instead, the summer of my victimization. And instead of opening me, Jake's attentions might have closed me down in fear and confusion. |

|

|||

|

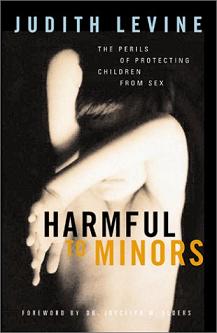

Levine at 14: Blossoming under the lens of her counselor's camera |

The photographs were another kid's idea. Jake and I and a few other campers were messing around in the dining room after supper early in the summer, and a boy named Ezra suggested I model for Jake. "Judy would make a gas model," he said. Gas, in 1967, meant cool. And looking back, I have to say, I was a cool kid. I wrote poetry; I played guitar and piano pretty well. According to the adults who knew me then, I was precocious and perceptive. My friends remember me as witty and impassioned. I affected a late-beatnik-early-hippie look: skimpy tank tops worn without a bra (I didn't need one anyway), low-slung bell-bottoms that revealed the curve of my belly where it dipped between my hipbones. Come to think of it, the clothes weren't so different from the ones today's parents (who wore them as kids!) condemn for prematurely "sexualizing" their daughters. The clothes were sexy then; they are sexy now. And to this day I can almost taste how good I felt in them. Before that summer, I still considered myself a little ugly and plenty awkward. In my high school, girls like me, who didn't have pageboy haircuts and didn't wear mohair sweaters with matching knee socks—and worse, who were smart—were untouchable.

At camp, though, I had suitors to spare. That summer several boys pursued me. One wore wire-rimmed glasses—avant-garde at the time. Another kept pleading with me to take my first acid trip with him. I was unmoved. I idolized the glamorous Jake, who had spent a year photographing guerrillas somewhere in Africa, who drove a battered Volkswagen, who meditated at an ashram. And he—miracle of miracles—liked me, a lot.

He liked me, I felt, and he saw me—saw the person I was beginning to know as myself. I could read his recognition in the photographs. They are straightforward, not arty, not pushy. I posed as I wanted; he shot. My body in them is at that heart-stopping stage between baby plump and adolescent fleshy. My face varies from picture to picture: Here I am a giggly kid, here a dreamy near-woman. One photo, which still hangs on my mother's wall, shows me holding Queen Anne's lace, gazing into the distance. It's a bit hokey: I'm working hard at looking soulful. But Jake's camera didn't mock. It's as if he believed I really was thinking deep thoughts.

What I was thinking about was sex. I tried to seduce him. In the flowery fields where we often went, I struck what I thought were enticing poses, leaning back in the long, scratchy grass, arching my back to reveal a bit of belly, dropping a shoulder so that a strap would fall invitingly off. In the little hand mirror I kept in my bunk, I rehearsed sucking in my cheeks and pouting my lips. And in the evergreen-smelling nights, I fantasized the day Jake would ask me to take my shirt off, brush his lips over my nipples, then pull down the short zipper of my pants. I imagined the bristles of his beard as he kissed me there.

He never did. In fact, he mentioned sex only once that I remember, as I sat on the counter in his darkroom, watching his red-lit face concentrate on the images emerging in the trays (the smell of developing fluid is still erotic to me). He said, "There are two things I know I can't do while I'm working here: smoke pot or make love to a woman." Was that woman me? I closed my eyes for a second and imagined I was, pictured him stepping between my dangling legs, taking my face in his hands, and kissing me. I opened my eyes, unkissed.

Maybe Jake considered me a little girl, not a woman at all. But somehow, as he gazed at me through that lens, I began to see myself as a woman, at least a little. One hot sunny afternoon, shingling a roof with Jake and some other campers, I admired the muscles of his tan, bare back flexing with each hammer swing. The bitter-salty odor of his sweat drifted toward me on a breeze. "Hmm," I said to myself, smiling as I noticed that I liked the smell. "This must mean I'm growing up." Once, skinny-dipping, I felt my body go as liquid as the lake as I watched him climb onto the shore, the red-blond fuzz on his body beaded with water.

Today, camp policy, like that at many schools and community centers, might forbid Jake and me to spend those hours alone in a dark little room. The camp director might pull him aside and ask pointedly what we were doing out in the fields. A counselor might interrogate me about his actions and insinuate that he was exploiting me. She might even persuade me it was true.

Of the dozens of rolls he photographed, there are a few shots of me with my shirt off, folk-dancing in a downpour with some other girls. I remember stepping back toward him, breathless and ecstatic, my face hot in the cool rain. "You're amazing," he said, and raised his camera again. Today those photographs could be called child pornography, and Jake could be arrested for taking them.

He never touched me, except to drape an arm over my shoulder or sit close to me on a bench. He kissed me on the lips only once, mouth closed, on the last day of camp—and gave his boots to another girl, throwing me into paroxysms of jealousy. But he made me feel beautiful. He made me feel desirable.

Recently, the publication of my book Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex lit a conflagration among conservatives, who called for its suppression—and called me an apologist for, even an advocate of, pedophilia. Why? In one chapter, I suggest that statutory rape laws are often unjust and unrealistic. They not only criminalize consensual teen relationships and categorically deny teens the right to consent to sex, they erase the very possibility that young people might desire—or initiate—sex at all, especially with an older person. At the same time, the book says, we've come to suspect all adults as sexual con artists, cajoling kids through popular culture and advertising to want sex, or seducing or coercing them to have it, before their time. It's as if adults, should they find a young person sexually appealing, could never control their impulses.

My book acknowledges that kids desire —and I know they do, because I did—and this apparently makes me a pedophile's patsy. Writing the book, I often felt lucky that I came of age during the brief moment when young people's sexuality was considered lovely and good and when adults who appreciated it were not regarded as perverts. In the summer of '67, a man gave a girl the innocent gift of her emerging erotic self. I wonder if I could receive it with such happiness and grace were I a girl today.

|

04/16/2002 - Updated 10:58 PM ET

Experts debate impact, gray areas of adult-child sex

By Karen S. Peterson, USA TODAY

Sex researchers and academics are tussling over a topic that most Americans don't even want to think about: sex between adults and children. Some of these experts are making the startling assertion that not all sexual activity between adults and minors is necessarily harmful. The result is a questioning of one of the country's most strongly held taboos.

Parents and others may gasp at the concept, especially in the current climate of scandal over sexual abuse by priests. But some serious researchers and academics want to review the term "child sexual abuse," preferring a more neutral term such as "adult-child sex."

They do not say coerced sex is acceptable. Rather, they debate questions such as whether a 25-year-old man should be prosecuted for statutory rape if he has sex with his eager 17-year-old girlfriend. Laws vary by state.

How about if an older woman provides a sexual initiation for a teenage boy? It's a fantasy dear to the hearts of many young men and a frequent theme of TV shows and movies, including the classic Summer of '42.

Experts debate whether sex with an adult is more damaging for an adolescent girl than for a boy, as some research indicates. Also being discussed is whether it's really possible for a minor to initiate sex with an adult. However, if the older lover is an authority figure, such as a teacher, coach or priest, most respected social scientists say the power imbalance is clear.

The controversy is engaging some researchers at top universities. "I think the evidence has been clear for some time that child and adolescent sexual abuse does not always do harm in the long term," says David Finkelhor of the University of New Hampshire, one of the nation's foremost researchers on the sexual abuse of children. "That is the good news." One question now, he says, is determining if some youngsters are more mature and "able to consent to sexual relationships with older partners."

The belief that children can truly consent to sex with an adult horrifies critics across a wide spectrum. "Our major task is trying to figure out how to stop this nonsense, this justifying and encouraging adult-child sexual behavior," says Paul Fink, past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

"Is it open season on our children?" asks Stephanie Dallam, a researcher for the Leadership Council for Mental Health, Justice and the Media, a non-profit advocacy group for children that focuses on pedophilia.

The issue should not be blurred by talking about sex with a 17-year-old versus a younger child, Dallam says. "That is just one hill in the battle" pedophiles are waging, she says. "Once they have the 15- to 17-year-olds, then it will be OK with the 12- and 13-year olds."

There is still "a lot to be cleared up," Finkelhor says. The adult-child issue would be easier to deal with, he says, if America had fewer children who had been victimized and "so badly hurt by the imposition of adult sexual activities."

Alarmed critics often quote a list of negative effects Finkelhor has catalogued. His inventory includes depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, an earlier entry into sexual activity, a larger number of partners and a greater tendency to be sexually victimized later in life.

Discussions about adult-child sex are appearing in professional journals, including a special issue last month of the AmericanPsychologist, a journal of the American Psychological Association (APA).

Researchers are not trying willy-nilly to turn traditional American values upside down, says APA spokesman Rhea Farberman. There is no drive among mainstream mental health professionals or social science academics to "legitimize adult-child sex." But she says there are reasonable questions for research, including analyzing types of sexual activity that include everything from fondling to rape.

Defining terms is one of the problems researchers face, she says. "Your definition, mine and the researcher's down the hall can all differ. Are we talking about homosexual or heterosexual sex? What is sex? How old is a 'child' ?"

The APA thinks child sexual abuse is by definition abuse and is "immoral and wrong," she says. But "we can all agree it is a much more serious and potentially harmful situation when a 9-year-old is raped than when a 16-year-old has 'consensual sex' with a 19-year-old. We need to be very careful of what we talk about."

The adult-child theme has been picked up on TV shows such as Boston Public, Once and Again and Dawson's Creek.

Actor Peter Krause's character on Six Feet Under recently revealed his sexual initiation occurred when he was 15 with a woman 20 years older. And a sequel to the 1971 movie Summer of '42, in which an older woman pleasures a teenage boy, reportedly is in the works.

The debate has spilled over into a public battle over a book due May 1 on children and sexuality. Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex is from the University of Minnesota Press, a noted academic publishing house. The author, Judith Levine, is a respected journalist and activist who has been writing about sex and families for 20 years.

The book has prompted bitter attacks from critics who say its publication should be stopped. The University of Minnesota, which provides 6% of the Press' budget, responded to the criticism in early April by announcing an independent review of how the Press chooses what it publishes.

Contrary to what some critics say, the book does not advocate pedophilia, says Douglas Armato of the University Press. Instead, it makes a case for open and honest discussion about adolescent and children's sexuality. "We published a 300-page book, and people are paying attention to four pages of it," he says.

E-mails are running 2-to-1 against the book, Armato says, but a corner has been turned. "We are beginning to hear favorable things from those who say these topics must be addressed."

A number of respected groups including the Association of American University Presses released a statement Tuesday in support of the Minnesota Press and its decision to "enrich the public debate."

Levine's book focuses on the need sex educators feel to get solid sexual information to adolescents. Frightening them, overemphasizing the dangers from pedophiles and from predators on the Internet, and overprotecting them does more harm than good, she writes.

"In my book, I deplore any kind of non-consensual sex between persons of any age," she said in an interview. "But teens deserve respect for their decisions, and they need from us the emotional and practical tools to make good decisions."

Levine had sex with "a man in his 20s" when she was "about 17" and believes such sexual contact is not always harmful. But in her book, Levine goes much further. She applauds a Dutch age-of-consent law that permits adult sex with a child ages 12-16 if the young person consents. Either the child or the child's parents can file charges if the sex is coerced.

Reaction has been swift. "We are really appalled," says Fink, who also is director of the Leadership Council for Mental Health, Justice and the Media. "Children need to grow up unencumbered and unused by adults. This whole movement is justifying the needs of adults by utilizing children in a negative way."

Dallam says: "Children should be off-limits sexually. There is a concerted effort among certain academics to change society's basically negative attitude toward sex with children. They try to say scientific data show some children are not harmed, therefore society is wrong in thinking that this is harmful."

Others object passionately to Levine's book. Robert Knight of the Culture and Family Institute calls the book "evil." The institute takes its guidance from God and the Bible, its Web site indicates. "The book makes a case for pedophilia," he says. "I have not read it cover to cover, but I am familiar with its themes. She is drawing on quack science. It gives a scientific gloss to the arguments that child molesters use."

The American Psychological Association is once again coping with the hot-button issue of adult-child sex. A 1998 article in one of its more obscure publications, the Psychological Bulletin, created a firestorm that included a denunciation by Congress. Now a March 2002 special issue of the American Psychologist published by the APA examines how it handled what turned into a debacle of criticism and counter-criticism.

In the 1998 article, three authors analyzed 59 studies of college students recalling sexual abuse. The researchers reported that despite what many think, child sexual abuse "does not cause intense harm on a pervasive basis regardless of gender in the college population," although boys fared better than girls. And they concluded that some children experienced positive reactions in "willing" sexual encounters with adults, according to the March APA analysis of what happened after publication and why.

One of the authors — researcher Robert Bauserman, who was with the University of Michigan in 1998 — now says, "I have the feeling that if you don't say anybody under 18 is permanently psychologically harmed by any type of sexual experience," then you are called a supporter of pedophiles by critics. He has never, he says, called for lower age-of-consent laws or "changing social norms." Instead, he says, researchers "need to identify the situations and circumstances that produce the most harm."

Researcher Finkelhor says that, as a society, "We seem to have an extremely difficult time recognizing the need for boundaries. We will be talking about this subject for some years" to come.

Hello boys

Girls are getting

older younger - padded bras and thongs for pre-teens are this week's

controversy. But how do we foster a mature attitude to sex, asks Marina

Cantacuzino

Wednesday April 17, 2002

The Guardian

Acknowledging that your child is turning into a

sexual being is, for parents, one of the greatest challenges of adolescence -

especially when it seems to come so fast on the heels of childhood. I recently

made a few dismal attempts at offering sex education tips to my 12-year-old

daughter ("sex should be special," "virginity is a precious thing," that sort of

thing) - and all because that four-letter word, "boys", has entered her

vocabulary.

Like many parents, I've been taken unawares by the sudden onset of adolescence and am frankly aghast at the overt sexual behaviour of some of her peers. So much has changed since I was a teenager: back then, 14 was the age when the first girls in my class lost their virginity, while 16 was more normal and 17 or 18 the average. There has been a steady downward trend in the age of first sexual intercourse since the 1950s, when the average age was 21. Now it is 16 and, according to a survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles published last year, 30% of young men and 26% of young women report having sex before the age of 16.

A condition aptly named "precocious puberty" is one related factor: girls are becoming sexually mature younger. A hundred years ago, menstruation started at 15; today, the average age is 12. But, just as significantly, even pre-pubescent girls are encouraged to think of themselves as sexual beings. Pre-teens dress like Kylie, Mylene and Co in crop tops and hipster jeans. And now the high-street chain Argos has just launched a new lingerie line for girls, the Tammy range includes padded bras and thongs - for nine-year-olds.

If girls are having sex earlier than ever before, it can't help that we have no statutory requirement for sex education in schools to tackle the emotional aspect of sex and relationships. According to Simon Blake, director of the Sex Education Forum, "We know that if sex education meets certain criteria, it delays sexual activity but, unfortunately, adequate sex education in schools is very patchy. Mostly, it's too little, too late - and too biological."

Blake blames the high rate of teenage pregnancies less on our imperfect sex education than on British attitudes towards sex, drawing comparison with the Netherlands which has the lowest teenage conception rate of developed countries. "Although their sex education is similar to ours, they don't have the tabloid press or our smutty culture. They're very grown-up about sex and don't believe that telling a five-year-old that people have sex and enjoy it is going to hurt them," he says.

It seems a topical controversy. In the US, a book about children's sexuality, Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex (University of Minnesota Press), is already causing a storm, ahead of next month's publication. Its author Judith Levine argues that young Americans, though bombarded with sexual images from the media, are often deprived of realistic advice about sex. This heresy has been enough to provoke a campaign of vilification from commentators, activists and parents.

Jane Stanley, a freelance PR consultant from south London, agrees that you can't underestimate media pressure. She believes that girls like her 12-year-old daughter Millie are in danger of skipping a process of maturation: "Their behaviour is that of 16- and 17-year-olds - and they look like it, too - but they don't have the chance to find out what to think and feel about things."

She describes her daughter's social life as junior-league clubbing - ticket-only events for 12-16 year olds which, while well supervised, encourage young girls to dress up and wear make-up, in other words to rush forward to embrace a culture they're not mature enough to understand. "Millie is a little girl but looks sexually mature when dressed up. To some people, that's sexually seductive and might illicit a response from those people you'd least want to be interested in your child."

Dr John Coleman, director of the Trust for the Study of Adolescence and author of Sex and Your Teenager, believes some parents of teenagers today need to change their attitudes about teenage sex and drug use because society has changed. He acknowledges, though, that having sex too young can be both damaging to a child and distressing to the parent. "If a parent is deeply upset by their daughter already being sexually active at the age of 12 or 13, there's no point in locking the bedroom door. What's important is to tell her how you feel: in other words, say that you think it's far too young, but if they're going to do it, you're going to help them do it safely."

This is precisely the conclusion Stanley has arrived at. "If I felt Millie was about to have sex, I wouldn't give her a packet of condoms because that would be endorsing it, but I'd make damn sure she knows how to get hold of one. But I really hope she doesn't start yet. I was 16 when I first had sex and, by that age, I'd expect her to have reached a state of emotional maturity where she could take responsibility for her own decisions."

Judging from my conversation with six girls aged 12 and 13, it would appear that girls like Millie are only a step away from having sex. These girls seem confident and strong, and are proud to be asked about their sexuality. They inhabit a world where there is abundant discussion of sex, and the way they articulate their feelings suggests how much they've been raised on "soap" culture. They may not say it outright, but being sexually active is clearly considered cool.

All but one has kissed a boy, but none has yet lost their virginity. Significantly, only one enjoys snogging, though all aim to get better at it. Even at 12, these girls are being called "frigid" by boys who aren't getting what they want. Tara, 13, says she was at a party when a boy opened his flies and presented himself for a blow job. She told him to get lost. "I'd have bitten it," shrieks her friend, still in that twilight zone of finding sex both fascinating and disgusting.

At an age when the peer group is suddenly much more important than the family, it's not easy for parents. "Communication is the most important thing to focus on," says Dr Coleman. "Teenagers want to know their parents are concerned about them. If you can get that right, you've won half the battle." Stanley tries to keep the channels of communication open with her daughter, but at times despairs. "I'm doing my best, but I wish Millie was more comfortable discussing sex with me. I worry that I make it more difficult for her."

The girls I spoke to are well aware that, even though they're underage, condoms and pregnancy tests can be bought at most chemists - and now from Tesco's, too. They all know other girls their age who have lost their virginity; none apparently regretting it. Those girls they know who have had early experiences of sex are, they say, the ones least able to talk to their parents. Studies have consistently born this out, showing that the more parents talk and express their concerns, the more likely the child is to delay having sex.

But the pressure is intense: the girls claim to be constantly fending off boys. Some have repeatedly been asked for sex. "My answer is 'When I'm old enough'," declares Scarlet, the most assertive of the group, who wants to wait until 16, but suspects it'll probably be more like 14.

Tara is the most sexually aware of the group. "My mum can't believe I fancy boys already and tells me to take contraception because she's not looking after the consequences," she says. She confesses that she'd much rather her mother was like other mothers, anxious about their daughters becoming sexually active too young. "But at least," declares Tara, "it makes me more determined not to turn into the person my mum expects me to become."

·

Names have been changed

![]()

What's so bad about good sex?

"Harmful to Minors" author Judith Levine

talks about why American parents are afraid of their teenagers' sexuality, says

kids know the difference between coercion and consent -- and blasts critics who

say she advocates pedophilia.

By Amy Benfer

April 19, 2002 | In the introduction to her new book, "Harmful to Minors," Judith Levine writes, "In America today, it is nearly impossible to publish a book that says children and teenagers can have sexual pleasure and be safe too."

And once you publish such a book in America today, she can now add, it is nearly impossible to escape the wrath of those who believe that such a statement is nothing less than dangerous.

Since the publication of her book, which is subtitled "The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex," Levine has been set upon by a mob of furious critics, many of them of the opinion that the author, in at least one chapter of the book, has endorsed pedophilia. It is a predictable response, coming in the midst of general panic about child molestation by the clergy, and a Supreme Court ruling last week that reverses a ban on virtual kiddie porn. But it is also a groundless and inflammatory claim that Levine, a self-described expert in "the sexual politics of fear," does not find surprising.

If the process of researching the book -- which includes a look at campaigns against sex-positive thinking -- didn't prepare her for the firestorm following its publication, says Levine, certainly the experience of trying to get the book published gave her a hint of what was to come.

"Harmful to Minors" was rejected by many major publishing houses: One editor called the contents "radioactive"; another said that the timing "couldn't possibly be worse"; another asked her to remove the word "pleasure" from her introduction. And once the book was finally picked up by the University of Minnesota Press, it was the target of a campaign spearheaded by the conservative right to keep it from being published altogether.

Levine's book reached the shelves just as the sexual abuse scandal was enveloping the Catholic Church, a coincidence that spurred the author's detractors to focus on a single chapter in the book that questions the motivations behind "age of consent" laws. Levine suggests that the laws -- which define a "child" as a person 18 or younger, depending on the state -- fail to consider the complexities of adolescent sexual relationships.

Age of consent laws are made, writes Levine, by lawmakers who fail to "balance the subjective experience and the rights of young people against the responsibility and prerogative of adults to look after their best interest." Also in this chapter, Levine questions why teens continue to be prosecuted for having consensual "adult" sex at the same time that, in the area of violent crime, "children" as young as 11 are being prosecuted as adults.

The furor about "Harmful to Minors" began when conservative radio talk show host Dr. Laura Schlessinger denounced the book on the air. An associate of Schlessinger's, Judith Reisman, had brought the book to Schlessinger's attention, claiming that Levine was another in a long line of "academic pedophiles," who were trying to make pedophilia more acceptable. Reisman also alerted Robert Knight, director of the Culture and Family Institute at Concerned Women for America, who called the book "very evil," and launched a campaign on the CWFA Web site, asking Minnesota Gov. Jesse Ventura to halt publication of the book because it had been published under the auspices of the University of Minnesota.

In fact, nothing in Levine's book suggests that the author condones pedophilia. ("No sane person would advocate pedophilia," she said in her interview with Salon.) And, as it turns out, Reisman and Knight have admitted that they hadn't actually read much of Levine's book before they decided to campaign against it. (Reisman told the New York Times, "It doesn't take a great deal to understand the position of the writer. I didn't read 'Mein Kampf' for many years, but I knew the position of the author," while Knight told the same reporter that he had "thumbed through" the book.)

Of course, had they read the whole book, Reisman and Knight probably would have found ample reason to raise the conservative alarm. Levine takes abstinence-only sex education to task, arguing that it limits crucial discussions of contraception and abortion, while depriving teenagers of information they need to have safe sex. Indeed, says Levine, the programs, which are enthusiastically endorsed by conservatives as well as the Bush administration, frequently put teens at greater risk of harm. If abstinence is presented as the only "surefire way" to prevent pregnancy and STDs, she says, students get the impression that "birth control and STD prevention methods don't work." The result, says Levine, is that students in abstinence-only programs are 70 to 80 percent less likely to protect themselves when they do have sex, compared to students who were given accurate information on birth control and condoms.

Pressure from conservative groups has reached past Levine to the publisher, prompting the Minnesota Legislature to ask the University of Minnesota Press to submit to a process in which it must disclose how books are acquired, and the details of each book's peer review. (Levine's book was reviewed by five outside scholars, instead of the usual two.) Lining up to defend the book are a number of civil liberties organizations and book publishers, including the American Association of University Presses, the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression, the Association of American Publishers, PEN American Center, the Boston Coalition for Freedom of Expression, the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Office of Freedom of Information at ALA and the Freedom to Read Foundation. All have signed a petition condemning censorship and supporting Levine and the University of Minnesota. Regardless of the outcome of these debates, publicity surrounding the book seems likely to boost sales. The first print run of 3,500 copies has sold out, and the University of Minnesota Press has decided to print an additional 10,000 copies. And the book hit No. 27 on Amazon rankings before its official publication date; as of today, it was No. 54.

Levine, who says in retrospect that she's glad she didn't include an author photo on her book jacket, spoke to Salon from her home in Brooklyn, N.Y., about the book's critics, Britney Spears, virginity pledges, what really helps in stemming teen pregnancy and AIDS and the inevitability that each generation will believe its children are being corrupted more than ever before.

You've been accused by the conservative right of advocating pedophilia. How do you respond to that?

The first thing I have to say is that no sane person would advocate pedophilia. It seems ridiculous to me that I have to say that: It's a "When did you stop beating your wife?" kind of question.

Your readers might be interested to know what else the Concerned Women for America are campaigning against, besides me. They are against teaching what they call the "lie" of evolution in the schools; they're worried about the "homosexual agenda" of the Bush administration evidenced by the appointment of members of the Log Cabin Republicans, the gay Republican delegation. They are really incensed about the United Nations' Sustained Development Conference, which they said was promoting the "special agendas" of a number of things, including preservation of the world's ecosystems and human rights. So that's all I'd say about my detractors.

Their critique of your work seems to be based in a reading -- perhaps a misreading -- of the part in your book that deals with age of consent laws. I'd be interested to know how you arrived at the arguments you make for abolishing age of consent laws, and how that would apply to the pedophilia controversy plaguing the Catholic Church.

What age of consent laws are about is criminalizing consensual relationships. Statutory rape is the prosecution of a consensual sexual relationship; if it were non-consensual, it would be prosecuted under regular rape laws, which, I am here to say, are the greatest thing in the world.

What I say is that it is possible for teens to tell the difference between coercion and consent, and that most statutory rape prosecutions have to do with conflict within the family over the sexual lives of their children, most often their teen girls or gay boys. Trying to adjudicate or deal with those conflicts in the context of criminal law -- which only recognizes a perpetrator and a victim, guilt and innocence -- is really a primitive instrument for trying to figure out how young people can have relationships of true consent.

The priest situation is a perfect example of how sexuality always exists inside a culture. It can be a local culture like the Roman Catholic Church, or it can be a national culture, like Afghanistan. In that culture, you have secrecy about sex, you have prohibitions against homosexuality, and, most important, you have the requirement of complete obedience to authority. Those would be among the worst conditions under which any person, young or old, could be involved in a truly consensual relationship. The most important thing to look at is the conditions under which a person -- whether adult or teenager -- engages in sexual behavior that may be harmful to that person. It's not sexuality itself that is the problem.

That's also true when we return to the question of statutory rape law: What conditions would allow, say, a teenage girl to negotiate equally in a relationship, any relationship? I think she needs to feel good about her own desires, and also to be able to stand up for her own limits. She needs to have a life that's rich in other things -- like friends, and community and school. In general, young teenagers who have sexual relationships with adults also have other troubles going on in their lives, though it's not necessarily true 100 percent of the time.

The Dutch law has been brought up a number of times, and I've been attacked for saying that I support something like it. This law covers the ages 12 to 16: Anything under age 12 is considered sexual abuse, and above 16 is considered the age of sexual consent. [Under the Dutch law, children between the ages of 12 to 16 have "conditional" sexual consent; i.e. sexual intercourse is legal, but they or their parents can press charges if they feel they are being coerced.]

In the United States, if we were to have such a law, it might not begin as young as 12; we may not say 16 is the age of consent. But the really important principles underlying that law are the two most important principles, in my opinion, that one must consider in dealing with childhood sexuality: On the one hand, it respects that teenagers and young people have sexual desires, and that they can make autonomous decisions about their own sexual expression; on the other hand, it recognizes that children and teens are weaker than adults and are therefore vulnerable to exploitation by adults, so the law also protects them from that exploitation. And of course, that balance will shift depending upon the age of the child.

A lot of the examples you raised in your book of consensual sexual relationships between teens under the age of consent and persons who were considered to be adults, dealt with couples who were not that far apart in age. In one couple, the girl was 13 and her boyfriend was 21; another example you raised was of a 16-year-old girl and her 18-year-old boyfriend. Is there any case in which you would feel that the age difference alone would be indicative of a coercive relationship? Perhaps if the couple is, say, a 13-year-old and a 35-year-old? Or a 16-year-old and a 45-year-old?

There is a social worker named Allie Kilpatrick at the University of Georgia who did very nuanced and in-depth interviews with several hundred adult women about their childhood and teenage sexual experiences. When I asked her this exact question -- "Does age have any effect on their actual experience?" -- she said, "No." Having said that, I would reiterate that if a 13-year-old is having a relationship with a 35-year-old, I would say that that sexual relationship is probably symptomatic of other things going on in that person's life, which is the thing that would be most important to me.

So at that point, would you say that, rather than criminalizing the relationship, you intervene in other ways to break off the relationship, such as by talking to the child, or sending them to counseling?

If I were that 13-year-old's mother, I would intervene, yes. I would be worried about it. Would I be able to stop her if she were intent on doing it? Other than locking her in her room, I wouldn't be able to. But I would hope that I would be able to offer her something of what she is looking for from that 35-year-old. And if not me, perhaps it would come from some other adult in her life.

I think it's obvious that if a young teenager is having an affair with a much older adult, he or she is looking for some sort of a parental relationship more than a sexual relationship. You see this a lot with homeless kids, who have what they call "survival sex," where they trade sex for a shower, or a night in a bed instead of sleeping under a bridge. What they need is that bed, that adult companionship, and that shower.

One of the things I noticed in looking at the comments put out by your detractors is how "dirty" they made your book out to be. Do you see that as symptomatic of how any honest talk about sex is trivialized as being simply prurient?

A good example of that is the cover of my book, which shows the bare torso of a child. People have reacted to this book by saying that it is either prurient or pornographic on the one hand, or, on the other, that it is completely innocent. That to me shows that there is no image of a child, or any way of talking about childhood sexuality that doesn't fall into either one camp or the other. The idea that childhood sexuality could be anything but a problem, unless it is altogether expurgated, is something that I frequently come up against.

Another example would be the judges who look at images of a baby in a bathtub and see pornography. My judgment of that guy is that he has a dirty mind!

One of the arguments that we hear quite frequently is that childhood has been "sexualized" by the mass media -- Calvin Klein ads, TV, etc. -- in a different way than it ever was before. Do you think there is any truth to that?

I don't like the word "sexualize" so much. It implies that children wouldn't otherwise be sexual if we didn't subject them to propaganda. We might be comforted by the fact that there has never been a generation that hasn't looked to the media as corrupting its youth. Before there was pornography, there was MTV, and before MTV, there was rock 'n' roll, before rock 'n' roll, there was comic books, before comic books, there was dime novels, before dime novels, there was burlesque. And yet each generation of youth somehow managed to grow up and be morally upstanding enough to decry whatever they felt was happening to the next generation.

As you pointed out in your book, many childhood development experts, such as Dr. Spock, and to some extent, Penelope Leach, were very adamant in labeling sex play as a normal part of childhood. I've noticed lately that people have become more and more fraught over the issue of what constitutes childhood sex play. Some experts even say that sex play itself is a sign that a child has been sexually abused.

There doesn't seem to be any evidence that this generation of children is engaging in any more "sexual rehearsal play" than previous generations. And, as I point out in the book, sexual rehearsal play is so normative throughout the world that anthropologists call it "sexual rehearsal play." They see it as a part of children's sexual development at every age, in every culture, as far back as they've ever studied.

This generation of kids seems to have absorbed a lot of sexual conservatism, even down to their pop heroes, like Britney Spears. Teen pregnancy and teen sex rates both dropped slightly during the '90s, at the same time we're seeing the rise of so-called virginity pledges. Do you think this generation is rebelling by being less sexual than their parents' generation?

The girls who idolize Britney Spears are in the age group the marketers call "tweens." Once they actually become old enough to have sexual desire, I don't think that their idolizing Britney Spears is going to stop them from acting on those desires. In fact, it apparently doesn't even stop Britney.

The drop in teen pregnancy, I would attribute to the use of condoms, and that seems to be what the Alan Guttmacher Institute and everyone else says.

I think that if kids are abstaining, it's mostly out of fear. And it's not simply fear of AIDS and pregnancy. What a lot of kids tell me is that they have this sense, like we did in the early '60s, that any misstep could really mess them up for a long time. It's a sense of huge consequence to anything you might do sexually -- it may do damage to your reputation, or you may have an abortion that you will regret for your entire life. I do think that kids have absorbed, if not so much conservative values, the overall message of conservative teachings, which is fear about sexuality.

Most of the daughters of feminist mothers that I know are not signing abstinence pledges. The people who are signing abstinence pledges are Christian kids. The conservative message is definitely working with young people on the issue of abortion. And I think that pro-choice people have unwittingly aided that by saying that abortion is always a tragedy, that it is really terrible, and difficult to go through.

But it's all just a guess. We really need some data on what kids are doing and feeling and thinking. That would help them, in perhaps educating them better, would help us in perhaps helping to prevent the spread of HIV. But the right has succeeded in shutting down all state funding of such research.

Before the decade in which birth control and abortion on demand were widely available, sex was dangerous; you could irrevocably change your life, or even die from sex, whether from a botched abortion, or an untreated STD, or even in childbirth. And then immediately, within a generation after sexual liberation, in the '80s, with the advent of AIDS, we were returned to a situation in which sex could be lethal.

What would you say to the argument that perhaps the attitudes boomers were raised with, that sex is healthy, that sex can be purely for pleasure, that sex shouldn't be feared, is itself a historical aberration?

I think there is some truth to that, but certain of the changes that happened in the '60s and the '70s through various sexual liberation movements mostly benefited women and gays. What people like Gloria Jacobs, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English said about the sexual revolution was that it was a revolution for women. Men had always done what they wanted to do, and they continued to do what they wanted to do, and I think that is still true for boys.

We're still looking at women and girls. Some of what I consider to be advances of that time -- such as women being recognized as having desire -- have stuck. The right is doing a rear-guard effort to turn that back, but I think it's very hard.

When we look, for instance, at the rate of sexual intercourse for teenage girls, it's now about at the level where it was in 1984, which is right around half -- 54 percent or so. But also history is a little more complicated. For example, in the 1950s, America had the highest rate of teen marriages in the industrialized world.

I love the joke in your book that defines a "conservative" as a "liberal with a teenage daughter." But a lot of boomer parents that I know, while they may realize that they are perpetuating a double standard by expecting their children to practice more conservative sexual behaviors than they themselves did, justify that expectation because they still feel very strongly that sex has changed because of AIDS.

Well, sex has changed because of AIDS. But the question is: What are we going to do about that? A good example is to look at the gay, middle-class urban communities during the height of the AIDS epidemic during the '80s. Their strategy was to use a sexually open culture, a culture of enormous sexual creativity, and lots of public discussion about sex (and even public sex!) [to combat AIDS].

A sexually open community was able, through that very openness, to stem the tide of the infection. Now when we see who is getting HIV, it's people who live in communities that are often repressive about sex, certainly repressive about homosexuality, where people are outside of the institutions where they might be able to get good sexual information.

You point out in your book that a lot of the kind of sexuality education that you advocate -- emphasis on pleasure, open knowledge -- was fairly prevalent throughout the '80s. I found it strange to notice that sex ed seemed to be more informative and open during the Reagan years than it was during the '90s.

There is always a lag between political activism and results. In 1981, the American Family Life Act [which advocated abstinence -- called chastity at the time -- as the basis of sex education in public schools] was put on the docket in the House of Representatives. It was from then on that the religious right began -- in Washington and in local communities -- its very successful campaign against sexuality education. The Reagan administration gave these people a platform that they had never had before, and all of these agencies -- health, education, welfare -- were headed by people who were against sex education.

You had more influence from the religious right in Washington, and a very sophisticated and smart grassroots movement, which often consisted of a tiny minority of people in a community. But many people were complacent, in the same way that I think many people in the pro-choice movement were complacent about abortion rights, and they didn't stand up for sexuality education.

It's a hard thing for anyone in the legislature to, say, stand up for talking about masturbation in school. So you had no defense, and a very strong offense against sex ed. We began to see the results of that later in the '80s, and certainly in the '90s.

Should we even try to continue to keep open sexual education in the public schools, given the near-impossibility of reconciling everyone's politics? Why not send children to outside programs in their community, like Planned Parenthood, who aren't censored by the politics of the community and the school board?

Among mainstream sexuality educators, there has been the suggestion that maybe we should give up on the public schools. I think that's very ill-conceived. Most people will go to public school. It's hard enough for community organizations to fund anything. At least, if there is good education in the schools, every kid will get a little bit of information. But it's also very important to have other sources of information for kids that they can access by themselves -- in the library, on the Internet, etc. And you also have to take care of the vast number of kids who are not in school -- who have dropped out, or are not living at home, or whatever.

There's a big difference between the sexuality education that goes on in mainstream public schools and the education that one would get at a community organization like Planned Parenthood. It's not only because people outside of school have more freedom; it's also because the kind of people who enter those jobs tend to come from an activist, rather than a professional background. Many of them are gay or lesbian, or youth activists. They have a different attitude right from the get-go about sexuality education.

Sex education has a conservative history. It's main goal has always been to stop kids from having sex. Even progressive sex education has often had that as a goal.

In your book, it seems to come out that sex education directed at gay kids might be even better than that which is directed at straight kids, in that gay kids who look to community organizations have adults who are extremely concerned that they have the best resources available.

Yes, well, if only the gay kids weren't getting beaten up in school.

But it is true. One of the things I say in my book is that at least a gay kid comes out as having a sexuality, and thus you have to deal with them as a sexual person. I think the best sexuality education, and the best attention to the whole child and the teen, has often come from the gay and lesbian community.

You can say to straight kids, "Don't have sex until you get married," but if you tell gay kids that they can't get married, there is not much they can do. Actually, I suppose the right is still saying to them, "Don't ever have gay sex until you die." But for those mainstream educators in the middle, to deny the existence of those who might be gay in your classroom is certainly not serving every student's need.

What do you make of the great oral sex scandals of the late '90s? Suddenly every newspaper seemed to have a headline story about oral sex, or sex parties, or how kids today look at oral sex differently than their parents' generation did. I'm sure a lot of this had to do with Clinton, given that they all came out around the same time.

Do you see evidence that children's sexual behavior is shifting toward having more oral -- and some reports even say anal -- sex than previous generations? And if so, is this a response to a fear of sexual intercourse?

The little research that we have shows that kids are doing oral sex, and sometimes anal sex, more. It's still a tiny statistical minority of kids who have claimed to have anal sex, but in the case of oral sex, not only do they do it more than intercourse, and maybe more than previous generations, but to me the interesting part is that they assign a different meaning to it than their parents' generation did.

In my generation, oral sex was something you did with someone you were intimate with. For them, it's less intimate, and vaginal intercourse means more. I remember even in the '70s, in cultures that valued vaginal intercourse very highly, you would hear anecdotes about young women who had anal intercourse and believed that they were still virgins. I think those rumors were highly exaggerated. They didn't come from any real data.

As for the idea that younger and younger teens are engaging in oral sex, there doesn't seem to be any research that shows it's actually happening. It's usually presented in the context of this "one private school" where one 13-year-old girl said that this other girl had oral sex.

Sexual behaviors do change throughout history, and AIDS has had an impact on sexual behavior. It makes sense. If teens are engaging in oral sex mutually, that is, boys doing it to girls, as well as girls doing it to boys, and they were using a latex condom, then it's not necessarily a good thing or a bad thing. My concern is more whether people are doing things that they really want to do, and are not doing it because somebody else said they should. If teens want to have pleasure in sex, it's crucial that they have a repetoire of safe sex behavior.

Of course, girls have a much higher risk of AIDS transmission through oral sex than boys do.

Yes. At the very least, they should use a condom.

Recently, I ran across a story on the wires about a group of 9-year-old boys who were performing oral sex on one another in a public school classroom. Does that test the limits of what you would consider to be normative sex play?

Well, I don't think kids should be having sex in class. Yes, I would say that I am definitely against oral sex in the classroom.

Fair enough. I suppose the more nuanced question, which you deal with in your book, is how do you deal with that? Do you criminalize it? Do you treat them as deviant?

The word "deviant" just means different from the norm. I would say that, in general, criminalizing sexual behavior that is consensual is a bad idea. The thing that I say in my book is that it makes perfect sense to me that if a person is going to act violently in our culture, that sex might be the means with which they do it. We live in a culture in which sex is the lingua franca of just about everything -- of the market, of love, of hate, of everything.

Furthermore, it's very important for kids to learn not to push anyone to do anything they don't want to do. To me, sex is not a separate category of that: You don't hit people, you don't take their toys, you don't force them to give you a dollar, and you don't force them to touch your penis.

If we are trying to teach kids to respect each other, to get along in their community, those are values that we need to inculcate in them in every realm of their lives. I would hope that the sexual would just naturally flow from those values of how you live with, and how you treat, other people.

Some critics have called your book "not parent-friendly." How do you respond to that?

Parents understand that their job is to be able to send their kids out into the world. While they want to protect their children, they are also thrilled with their children's independence. There's no more exciting moment than when your child toddles off on his tricycle for the first time and doesn't look back. It's sad, but it's also exciting. If they feel that they can't do that in the realm of sexuality, I think that's a sad and difficult thing.

I would hope that I'm being helpful to parents, not only in sorting out the real perils from the exaggerated ones, but also in giving them some ideas of the ways in which they, and other people in their community, can help to guide their kids into a happy and safe sexuality.

I did notice that most of the parents quoted in your book sounded like pretty progressive types. There were several gay parents, feminists, academic families. Do you feel a sense of preaching to the choir in that regard?

I don't actually talk only to progressive parents. One mother I talked to, a working-class woman, was the one who was quoted as being appalled when her daughter came home from school [after a "good touch/bad touch" workshop] and said, "Don't touch my vagina, Daddy." But I think you're right that a lot of the parents I talked to were mostly progressive parents. I was using them as examples of parents who had been relaxed about sex, and their kids were OK.

But even those parents had their fears. One very progressive woman I quoted towards the beginning of the book said that she was turning into an "ironclad conservative" about her son and sex, and not about anything else. I also had a conversation with about 12 other parents from her synagogue, which was pretty conservative.

I don't want to minimize the very real dangers that young people face from sex, but I also would like to try to move the discussion of child and teen sexuality out of the realm of "problem." That, to me, is really the crux of it. Progressives do the same thing. They get a grant, for example, to deal with teen prostitutes. And they can't get a grant just to deal with teens.

You seem to advocate a position of open discussion on demand, balanced with a tolerance for children's privacy, even closed doors.

I talk a lot about respecting the sexual privacy of even very young kids. I'm not sure that barging into their room and seeing them masturbate, then sitting down and saying, "Oh honey, let's talk about masturbation," is necessarily the best thing for that kid.

One early childhood educator that I talked to said, "Children need room for sexual transgression outside of adult eyes and outside of adult commentary." I thought that was a smart thing to say. Sexuality is something that is often private. As long as kids know that if something is hurting them, they can talk to you, or to some other adult, I think we need to respect their privacy.

My mother worked at a birth control clinic, and she would leave out books. And I always felt that was intrusive too; there was nothing she could do that was right.

Does that right to privacy extend into the teen years? Should parents still respect the privacy of their children behind closed doors, even with their lovers or potential lovers?

My parents did. During the sexual revolution, I did a story talking to parents about how they felt about their kids' sexuality. A woman told me a story about her 15-year-old daughter, who said, "Mom, I want my boyfriend to sleep over at home." The mother said that she felt that if the daughter was asking for her permission, she was also in a way asking for her participation. She said it almost made her feel as if her daughter was not ready to have sex, if she needed her mom there. That sounded wise to me. Sexuality is a way of moving away from your family, it's about forming intimacies outside the family; it really is not about the family, it's about the not-family.

This woman said to me, "Would I rather she were out under a bridge having sex than on the Upper West Side in my apartment? No, I wouldn't." But by the same token, in France it's very common for a teen's boyfriend or girlfriend to sleep over. I do think that teens are much more likely not to want to do it in the house when their parents are home, just as parents don't like to do it when their kids are listening. These are issues in which a hard and fast rule is not adequate. The aim of the right is to try to simplify what are very complicated issues.

When I gave my book to my mother, I inscribed it: "Thanks for teaching me the difference between right and wrong." And I feel my mother did that. But she also left me room to explore my sexuality. And as a result, I made some mistakes, and I recovered from them. But I do think what she and my father gave me were the tools to make good decisions and to be a moral person in the world, and that stood me well.

About the writer

Amy Benfer is a writer living in San

Francisco.

Viewed on July 8, 2002

"Parents today have forgotten what it was like to be teenagers themselves," I conjectured recently. A friend and I were discussing why so many people find the issue of teen sexuality so terrifying. "No," he replied, "they're afraid because they remember exactly what it was like!"

Few issues cause as much consternation as the sexual lives of young people, a fact made abundantly clear to author Judith Levine and the University of Minnesota Press upon publication of "Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children from Sex."

In the furor over the book, most commentators have missed Levine's main point: "Sex is not ipso facto harmful to minors." In fact, "America's drive to protect kids from sex is protecting them from nothing. Instead, often it is harming them."

Despite what critics contend, "Harmful to Minors" is not about pedophilia. It tackles a wide range of issues including censorship, statutory rape laws, abstinence-only sex education, abortion, gender, AIDS, and child welfare. The latter issue, which raises questions beyond sexuality about how our society provides for its neediest children, is "the most important one in the book," Levine told AlterNet, and "the real reason the right is against me." But the inflammatory issue of child-adult sex continues to draw the headlines.

Why does the proposition that youth deserves sexual autonomy, pleasure, and privacy seem so radical? In the 1970s, the sexual revolution was in full swing and the idea that children and teens were sexual beings was accepted, at least among progressives. Books such as Heidi Handman and Peter Brennan's "Sex Handbook: Information and Help for Minors" and Sol Gordon's "You!" showed respect for young people and their ability to make their own sexual decisions.

For the past two decades, though, the religious right has been winning the war against comprehensive sex education, access to abortion and contraception, and the sexual autonomy of young people. By the late 1980s, Gordon had shifted his advice toward parents with "Raising a Child Conservatively in a Sexually Permissive World," and child pornography laws made it illegal to even possess a copy of "Show Me!," an award-winning sex education book for children.