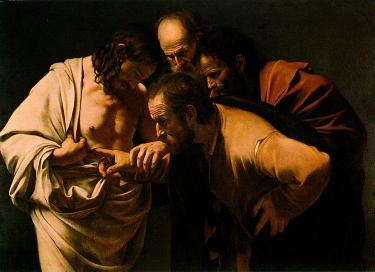

Whatever we may feel about Carracci’s methods, Caravaggio and his partisans certainly did not think highly of them. The two painters it is true, were on the best of terms – which was no easy matter in the case of Caravaggio, for he was of a wild and irascible temper, quick to take offence and even to run a dagger through a man. But his work was on different lines from Carracci’s. To be afraid of ugliness seemed to Caravaggio a contemptible weakness. What he wanted was truth. Truth as he saw it. He had no liking for classic models, nor any respect for “ideal beauty”. He wanted to do away with convention and to think about art fresh. Some people thought he was mainly out to shock the public; that he had no respect for any kind of beauty and tradition. He was one of the first painters at whom these accusations were leveled and the first whose outlook was summed up by his critics in a slogan: he was condemned as a “naturalist”. In point of fact, Caravaggio was far too great and serious an artist to fritter away his time to cause a sensation. While the critics argued, he was busy at work. And his work has lost nothing of its boldness in the three centuries and more since he did it. Consider his painting of St. Thomas, in the figure, the three apostles staring at Jesus, one of them poking his finger into the wound in His side, look unconventional enough. One can imagine that such a painting stuck devout people as being irreverent and even outrageous. They were accustomed to seeing the apostles as dignified figures draped in beautiful folds – here they looked like common labourers, with weathered faces and wrinkled brows. But, Caravaggio would have answered, they were old labourers, common people and the unseemly gesture of Doubting Thomas, the Bible is quite explicit about it. Jesus says to him: “Reach hither thy hand, and thrust it on my side: and be not faithless, but believing” (St John XX, 27).

Click to see a larger image

Amor Vincit Omnia

c. 1601-02

Oil on canvas

75 1/4 x 58 1/4 in (191 x 148 cm)

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin