12-12-2002

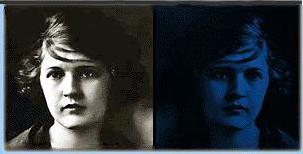

ZELDA

FITZGERALD

(1900 - 1948)

Unwell, this side of paradise

Elaine Showalter on the

sordid power struggles behind the decline of the Jazz Age's golden couple, Zelda

and F Scott Fitzgerald

Saturday October 5, 2002

The Guardian

Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice

in Paradise

by Sally

Cline

512pp, John Murray, £25

Dear Scott,

Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

ed Jackson R Bryers and Cathy W Barks

387pp, Bloomsbury, £20

|

"I used to

wonder why they kept princesses in towers," the romantic and possessive young

officer F Scott Fitzgerald wrote to the Alabama belle Zelda Sayre. Zelda was

charmed at first, but quickly noticed that he seemed obsessed with the image. "Scott,

you've been so sweet about writing," she replied, "but I get so damned tired of

being told that - you've written that verbatim, in your last six letters!"

Eerily, the

fairytale life they both imagined took on an ominous gothic form, as the

jonquil-haired boy and the golden girl, the most legendary couple of the 1920s,

faced the grim realities of alcoholism and mental illness, infidelity and

literary rivalry, of a marriage in which, according to their friend Ring Lardner,

"Mr Fitzgerald is a novelist and Mrs Fitzgerald is a novelty".

Zelda's

story was first told in Nancy Milford's splendid feminist biography of 1970; but

as Milford later wrote, Scottie Lanahan, the Fitzgeralds' daughter, was so upset

by the manuscript that she threatened suicide. Milford cut much of the detail

about Zelda's diagnoses, treatments and her homosexual crushes, and the family

restricted much of the medical material in the Princeton University archives.

|

|

|

|

Generally

biographers and friends have taken the side of one of the partners, at one

extreme endorsing Hemingway's view that Zelda was a madwoman who undermined

Scott's sexual and artistic self-confidence and drained him emotionally and

economically, and at another seeing Scott as a monster who drove Zelda mad and

destroyed her chances to succeed as an artist in her own right. Both of these

books take a more balanced approach, blaming neither partner; but the selection

from the Fitzgeralds' correspondence edited by Jackson Bryers and Cathy Barks,

and pre-emptively called "love letters", repeats the legend of a great and

timeless romance, while the exhaustively researched biography by Sally Cline

powerfully undermines it.

Without

making Scott the villain, Cline argues that both partners were victims of a

social system and psychological practice that punished creative women,

especially those married to creative men. Cline points out that Zelda's hospital

letters - which form the bulk of her side of the correspondence - were censored

by her caretakers, and have to be seen as written by a prisoner to her jailer.

Although she

often expressed an extravagant love for Scott, and he loyally supported and

wrote affectionately to her, they quarrelled bitterly and endlessly over her

ambitions as a writer and painter, her sexuality, and her right to work and to

be independent. Zelda repeatedly said that she wanted a divorce, but without any

money of her own, and without the means of earning any, she was utterly

powerless in the relationship.

Named for

the gypsy heroine of a sensational novel, Zelda had been the most popular and

daring girl in her set back in Montgomery, Alabama - a "top girl". By winning

her, Scott also engaged in an unconscious merger with his male rivals, perhaps a

version of the homosexuality he wrote about (through Nick Carraway's pick-up in

The Great Gatsby, for example), and violently repudiated. Zelda was also

original and imaginative: "I'm so full of confetti I could give birth to paper

dolls," she declared at a ball. Paper dolls were a metaphor for the

hyper-feminine domestic art of American women to which she was destined by her

birth and class.

The crack-up

of the marriage and their lives came quickly; by 1930, after less than a decade

of fame and high living in New York, the Riviera and Paris, they had entered

what would become a long decline. Just as their married life had been lived in

hotels, Zelda's post-1930 life became an odyssey between hospitals and clinics;

some were four-star European establishments with all the luxuries of a spa

resort, some much more basic and punitive with cold baths, strait-jackets and

long hikes.

A belated

effort to became a ballerina in Paris had driven her to anorexia and obsessive

behaviour, but Scott's chief reasons for having her committed were sexual; she

declared an attraction to her ballet teacher, and, in the asylum, was caught

masturbating. Her sexual frankness conflicted with his anxieties and pruderies,

especially with his own fascinated dread of homosexuality. "The nearest I ever

came to leaving you," he told her, "was when you told me that I was a fairy in

the Rue Palatine."

Zelda felt

that she had lived the life of a pampered child: "I don't seem to know anything

appropriate for a person of 30." Confinement in a series of institutions

certainly made it hard for her to grow up. Scott was a control freak who wanted

to arrange and order every detail of her life, as he would also for their

daughter, but he also did his best to find her the most advanced care.

Zelda's

doctors included many of the famous names of psychiatric medicine of her day,

but their understanding and treatment of women's psychological conflicts was

lumbered with traditional expectations that healthy, normal women should be

content to limit themselves to secondary domestic roles. Zelda was forced to

restrict or give up her dancing, painting and writing and to submit to versions

of the rest cure that made her worse. As she wrote: "Enforced inactivity maddens

me beyond endurance."

Diagnosed as

schizophrenic, although she did not meet most of the criteria for the illness,

Zelda was regularly subjected to insulin shock therapy, which induced memory

loss and weight gain, and dosed with a battery of drugs including morphine,

belladonna, potassium bromide and horse serum. From the beginning, Zelda

perceived her treatment as "a sort of castration". Scott, meanwhile, was not

institutionalised for his drinking. Moreover, he insisted that she was the real

drunkard, while he needed drink in order to work.

The biggest

crisis in their marriage and its tenuous balance of power came in 1932, when

Zelda wrote an autobiographical novel, Save Me the Waltz, drawing on the same

material with which he was struggling in Tender is the Night. Scott was outraged

that Zelda should presume to poach on his territory. He wrote in fury to his

publisher Max Perkins, to whom she had sent the manuscript, telling him not to

publish.

In May 1933,

the Fitzgeralds sat down with Zelda's doctor for a debate on the subject which

was transcribed by a stenographer and ran to 114 pages. The transcripts, Cline

says, read more like a trial than a negotiation. Scott demanded "unconditional

surrender" - he accused Zelda of being an opportunist and called her "a

third-rate writer" and a "useless society woman" with an "amazonian and lesbian"

personality. "It seems to me that you are making rather a violent attack on a

third-rate talent then," Zelda replied. She wanted a divorce and stressed her

need to be independent.

In a journal

entry outlining his divorce strategy if Zelda insisted on continuing to write

fiction, Scott noted: "Attack on all grounds. Play (suppress), novel (delay),

pictures (suppress), character (showers), child (detach), schedule (disorient to

cause trouble), no typing. Probable result - new breakdown." In the event, Zelda

capitulated and Scott allowed the novel to be published with several cuts.

Zelda's

letters are saturated with the need to find meaningful work and to support

herself. But Scott could not consent, and gradually Zelda developed symptoms of

religious mania and suicidal depression.

In the late

1930s, when Scott was too hard up to pay her hospital fees, he moved her to

Highlands Hospital in North Carolina, where Dr Robert Carroll believed in

vigorous physical activity and reprogramming rebellious women through

electro-shock treatments into "wholesome" wives and mothers. Although Carroll

eventually relented enough to support Zelda's painting, he was also involved in

a case of raping a female patient. Another psychiatrist, Dr Irving Pine, told

Cline that "Dr Carroll took advantage of several women patients, including Zelda".

Scott

predeceased her, in 1940, and after his death, Zelda spent much of her time in

Montgomery with her family. Cline argues that the years until her death in 1948

were among Zelda's most creative, although her unfinished novel from the period,

Caesar's Wife, is the product of her religious obsessions.

In 1975, the

Catholic archdiocese overturned an earlier decision and allowed Scott and Zelda

to be buried together in St Mary's Church cemetery in Rockville, Maryland. Their

inscription quotes the last line of Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the

current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

The

Fitzgeralds had many admirable qualities, and, separately and together,

exhibited far more of Hemingway's "grace under pressure" than Hemingway did

himself. But Cline's clear-headed and careful study should make clear that their

relationship can no longer be regarded as a great love story. Instead, it

demonstrates the terrible danger of such romantic fairytales, and the melancholy

dangers of a culture, like that of the American South or the Lost Generation,

that sacrifices the present to the imagined glories of the past.

Elaine

Showalter's books include Inventing Herself (Picador)

LINKS:

ZELDA

Biography

Bibliography

Quotations

Artist

Museum

Zelda and the Jazz

Age

SCOTT

Biographies

O

O

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Centenary

F. Scott Fitzgerald's

The sensible Thing

The F. Scott Fitgerald Society Home Page

"Sometimes Madness is

Wisdom. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald: A Marriage"

By Kendall Taylor

Ballantine Books

416 pages

Biography

For the love of literature

Scott Fitzgerald stole Zelda's ideas, plagiarized

her diaries and even pushed her into an affair. He was arguably the worst

husband of his generation -- and that made him its best author.

By

Jonathon Keats

| |

|

|

Aug. 25,

2001 | When F. Scott Fitzgerald's second

novel was published, a newspaper editor asked the author's wife whether she'd

consider reviewing it for the New York Herald Tribune. As she read her husband's

book with the sharp eye of a paid professional, she recognized not only the

autobiographical tenor of "The Beautiful and Damned," but also, cleverly

attributed to a female lead much like herself, whole passages authored by her:

|

"It

seems to me," she wrote in her review, "that on one page I recognized a portion

of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my

marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to

me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald -- I believe that is how he spells

his name -- seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home."

She

was being modest. The truth is that Scott used a great deal of Zelda's writing,

credited to characters he modeled after her, in every book he completed in his

abbreviated life. That Zelda was Scott's muse is hardly news, and it comes as no

surprise that her frank sexuality, the wild abandon with which she flaunted her

body at parties, gave color to his stories: More has been written about the

Fitzgeralds, their antics and affairs, than they can possibly have known about

themselves.

Yet,

while others have certainly noted the spill of life into art, and even marked

passages of Scott's books actually written by Zelda ("What grubworms women are

to crawl on their bellies through colorless marriages"), Kendall Taylor's new

biography of the couple, "Sometimes Madness Is Wisdom" (to be released in

September) is the first to provide adequate groundwork for a thorough account of

literary custody. Examining sources new and old to find just where within the

Fitzgerald home plagiarism began, and at what madhouse it ended, Taylor attempts

to make the case that "In effect Zelda was Scott's co-author."

Taylor's documentation is formidable, and were she simply out to argue that

Scott could be a despicable creature, a liar and a cheat and a philandering

drunk, we could shrug our assent and go back to Gatsby's house party or Dick and

Nicole Diver's swath of Riviera beach. But the contention that, as literature,

Scott's novels are in any meaningful degree a creation of Zelda is as

insupportable as that the Mona Lisa be reattributed to the young wife of

Francesco del Giocondo who sat, with that famous smile, as its model.

Technically, Scott was a plagiarist. Artistically, that makes no difference.

Like

their marriage, the Fitzgeralds' creative relationship went to extremes no

couple could be expected to endure, not quite innocent from the start. Young

Scott, an Army lieutenant stationed in Alabama awaiting orders to fight

overseas, had always found it easy to interest girls by talking up his literary

ambitions and asking them, "What sort of heroine would you like to be?" He

quickly perceived, though, that to attract 17-year-old Zelda Sayre would demand

more: Locals had to wait months for a date, and Army aviators vying with one

another to get her attention regularly flew stunts over the Sayre family home

risky enough to cause a collision.

So

Scott, suited in a uniform of Brooks Brothers cut, not only boasted that he

intended to be a famous author and had Francis Scott Key as an ancestor, but

also suggested that the female lead in his novel-in-progress was a girl a lot

like her. That was true -- albeit only because she resembled the young heiress

who'd dumped him in Chicago. Still he intrigued her, enough to take him

seriously, and try him out sexually, in spite of his poverty and her intention

to marry wealth.

A

tacit agreement was reached. As she expressed it to one of his Princeton

classmates, "If Scott sells the book, I'll marry the man, because he is sweet."

After that, she gave Scott all her support, sending him love letters full of

spirited encouragement and quotable wit: A running account of night after night

on the town with the heir to one or another Southern fortune.

Stung

by jealousy, Scott used those letters, as well as material she let him copy from

her diaries, to nuance the novel that would become "This Side of Paradise," a

book he almost wholly rewrote to meet his image of her. But, while he flattered

Zelda by showing her scenes in which she was depicted as could only be

accomplished by a spectacularly talented writer in a state of hopeless

infatuation, she cut off all sexual relations with him, and locked the

engagement ring he'd offered her (borrowed from his mother) away in a box until

he proved himself a literary success.

"This

Side of Paradise" was rejected by Charles Scribner's Sons twice, with massive

revisions including an about-face from first-person to third. Finally the

estimable publisher of Henry James and Edith Wharton offered to print an initial

run of 5,000 copies. After that, Zelda tentatively consented to an engagement,

and when Scott bought her a diamond-studded wristwatch from Cartier with the

earnings of a story he sold to the movies, her parents made their plans public.

Yet

Zelda, romantic pragmatist, refused to marry Scott until the novel was in print.

She'd broken off his attempted engagement once already, using words he'd

promptly written into his book. ("I can't be shut away from the trees and

flowers, cooped up in a little flat, waiting for you. You'd hate me in a narrow

atmosphere. I'd make you hate me.") If the book flopped, Zelda Sayre, Southern

belle, could always replace her beloved with any moneyed bachelor she liked.

His

book sold. More than half the edition ran out in the first three days. Almost as

quickly, Scott got Zelda to a church and, without waiting for her parents or

his, had her to hold -- for richer and poorer -- in their honeymoon suite at New

York's Biltmore Hotel. There they stayed for weeks. As he explained to one

reporter, "I married the heroine of my stories."

Ring

Lardner Jr. had a different way of phrasing it: "Scott is a novelist and Zelda

is a novelty." The Fitzgeralds were New York's most notorious couple in the

early 1920s, and by encouraging Zelda's antics, Scott had material enough to

supply countless short stories to the Saturday Evening Post at an obscene $2,500

apiece -- $25,000 by today's standards -- funding their dipsomaniacal lifestyle

while reserving for his second novel the most memorable episodes.

Zelda's behavior remains almost as mythical as Scott's fiction: Her fountain

dives and dancing on tabletops, and her outré way of making Scott's friends help

her undress and bathe her, were astonishing enough that William Randolph Hearst

hired a reporter to cover the couple full-time. But Scott proved more diligent

still, writing down on odd scraps of paper for future adaptation anything

amusing his wife did or said. He was even there to record her words at the birth

of their child: "Goofo, I'm drunk," Zelda told him. "Isn't she smart -- she has

the hiccups. I hope it's beautiful and a fool -- a beautiful little fool." That

language appeared several years later in "The Great Gatsby," with Daisy saying

of her newborn child, "I'm glad it's a girl. And I hope she'll be a fool --

that's the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool."

Zelda

may have been right. In any case, already her own life was beginning to go

wrong: Both she and Scott must have been aware of the precarious role she'd

taken, and both seem to have been equally eager to avoid seeing the inevitable

catastrophe, the catastrophic inevitability, of continued acceleration. That's

the context of her most serious affair. They were living on the French Riviera

by then, Scott busy with "The Great Gatsby." As Zelda's sole occupation was as

the famous novelist's novelty wife, she found herself out of work while he

wrote.

Naturally she was bored. So she found someone new to interest her, and to make

her, once again, more interesting to Scott than mere fiction. The man was a

French lieutenant, as dark and handsome as required, given the role he had to

play. At first Scott encouraged the time she spent with him, but what began as a

convenient distraction became a serious matter when Zelda informed her husband

that she'd fallen in love and wished for a divorce.

Scott

wasn't ready to lose his best character, and ended the affair by force. Whether

that involved a duel, as he later boasted to a mistress, seems doubtful, but it

hardly matters since the month-long house arrest he inflicted on his wife

effectively broke her will. That he could mete out such a punishment is

distressing, and the danger done to her psyche would haunt them both to the

grave, but more disturbing still is that he later confessed to encouraging the

affair before he crushed it. He recognized that by watching his wife's behavior

toward her French lover, he could depict Daisy's affair with Gatsby with greater

veracity. So human decency bowed its head to artistic excellence, and somewhere

within the misery of two people, neither quite innocent, was born "The Great

Gatsby," novel of its generation.

Things

went from bad to worse for Scott and Zelda both. As in Jay Gatsby's life, the

affair marked a turning point in the Fitzgerald marriage. Just how it

contributed to Zelda's madness and Scott's alcoholism is open to speculation,

but one clear effect was Zelda's determination to find her own voice apart from

Scott's novels. She didn't mean to do so through writing. Her first passion was

for ballet: She meant to be the next Isadora Duncan, an almost impossible goal

made still more difficult by her age and lack of practice since childhood.

Nevertheless, she enrolled with one of Europe's premier instructors, a woman

retired from the Ballets Russe, and worked herself so hard that she and Scott

barely even spoke. He resented the expense of what he considered a waste of her

time, and she despised equally her financial dependence on him.

So, to

earn some of her own money, she did what came naturally to her in all those

letters and diaries: She wrote stories. Scott's agent got top dollar for her

prose sketches of popular female types, but only by selling them under their

joint byline, or, in the case of one piece the Saturday Evening Post purchased

for $5,000, under Scott's name alone. The articles were well done, but certainly

not literature, and if Scott got credit he didn't deserve, Zelda made money on a

reputation she hadn't earned. It hardly seems worth determining who got the

better of whom.

But

what happened when Zelda opted to write her own novel is another matter. She

intended "Save Me the Waltz" to be a bestseller, and he intended to prevent her

from writing it in the first place. His claim to her life as literature had

already been challenged a decade earlier when Smart Set editor George Jean

Nathan offered to publish her diaries. Zelda expressed interest, but Scott

insisted he needed them as "inspiration" for future novels, to support their

extravagant lifestyle. He got his way, she had a brief affair with Nathan and

all was forgotten.

Matters were rather different 10 years later. "The Great Gatsby" had been a

financial failure, and a mental breakdown had forced Zelda to give up ballet.

Sexually estranged and alienated by Scott's public courtship of a 17-year-old

movie starlet named Lois Moran, she saw the creative potential of authoring a

novel, and found in her unhappy marriage spectacular material. She argued in a

letter to Scott that their ruined life was "legitimate stuff, which has cost me

a pretty emotional penny to amass." Fearful for what damage an autobiographical

novel by his wife could do to his image, and for what would be left for him to

write, Scott browbeat Zelda into making paper dolls instead.

Another breakdown put her back into an asylum where she was encouraged to write

for therapeutic effect. She finished "Save Me the Waltz" and sent it to Maxwell

Perkins, Scott's editor at Scribner's. Perkins was impressed. Scott was not. "My

God," he said, "my books made her a legend and her single intention in this

somewhat thin portrait is to make me a non-entity."

That

novel is the only significant work completed by Zelda, and the version Perkins

eventually published was considerably abridged by Scott. In spite of extensive

damage done to make his character less obviously alcoholic, the novel is a work

of extraordinary beauty, written in a voice absolutely original and

pitch-perfect. Unfortunately, few have read it; Scott prevented Scribner's from

providing publicity, and a mere 1,392 copies sold. Nor was Zelda helped by his

judgment of her talent, an opinion he made so public that she parroted it in her

book: "I hope you realize that the biggest difference in the world," the

character she modeled on him proclaims, "is between the amateur and the

professional in the arts."

But

Scott was mistaken. Truth be told, the biggest difference in the world is

between life and art. That's the flaw in any argument on behalf of Zelda as

Scott's co-author. Maybe she would have been as good a writer as Scott. We can't

even rule out that she'd have been greater. But that's only because we lack

adequate evidence to judge. "Save Me the Waltz" shows that anything could have

happened had she realized her potential as a novelist. For a whole host of

reasons, she didn't. The only potential she ever realized was as a novelty.

Zelda

was the novelty of the decade, even the century, and we ought to appreciate the

originality that involves. Even had she not written "Save Me the Waltz," she'd

deserve as much credit as Scott for the role she played in making the '20s roar.

In all their antics, they were collaborators. They set one another up and

watched each other fall. But Scott did something more. He wrote novels that will

be read for as long as humanity endures. They will be read after anyone

remembers, or even cares, what happened in the decades they were written. They

will be read after the whole society they depict is gone. They will be read in

the spirit that we already appreciate Sophocles anad Shakespeare, for the high

color that great tragedy lends our perception of the human condition. And they

will be read for the redemption to be found in anything of true beauty.

Three

charges may be leveled against Scott in Zelda's bid for joint custody of his

literary progeny. The first, and most easily dismissed, is that he prevented her

from writing to protect his own work. Of course he's guilty as charged, and his

characteristic cowardice and intense jealousy (to which he readily confessed)

are no excuse for the abuse he inflicted on his wife. But that doesn't make a

difference when assessing his literature, any more than Jean Genet's prose is

less or more compelling on account of his criminal record. Contrary to what

Scott believed, greatness among authors is not an either/or proposition, and

words are in unlimited supply. Neither "Save Me the Waltz" nor anything else

that might have come from Zelda's pen could adversely affect the literary worth

of what was written by Scott.

So,

having roundly condemned Scott as a husband, we can turn to the serious business

of judging him as an author. The second case that might be advanced against him

is that he relied on Zelda so completely for inspiration that the part her

character plays in his novels isn't honestly his creation.

To

begin with, we make a crucial factual error when we assume that Scott acted just

as an observer. More to hold against him as a husband, sure: Anyone who would

encourage a spouse to have an affair for his benefit deserves to be divorced

with extreme prejudice. Yet the fact remains that most of what Zelda did, and

especially the stage on which she acted it out, depended on them both.

Maybe

her scenes belong to her at least in part? In life yes, but certainly not in

art. The crucial distinction is between originality and creativity. The former

is all around us, boundless. It may involve great wit, verve, beauty. What it

lacks, though, is any underlying structure. Zelda's novelty was a scene unframed

by a camera, a performance without footlights or curtain. Scott's work as a

novelist involved the organization of wit and verve and beauty into discrete

units of meaning. Even in "The Beautiful and Damned," his most autobiographical

novel and his weakest, Scott made the omissions and insertions that transformed

a senseless summer spent drunk on Long Island into an emblem of an era gone to

waste.

Scott

could be candid about the subservience of others, and even himself, to his work:

"I have just emerged not totally unscathed, from a short violent love affair,"

he confessed toward the end of his life in a letter to a friend. "Still it's

done now and tied up in cellophane and -- and maybe someday I'll get a chapter

out of it. God, what a hell of a profession to be a writer." He'd run himself

down, written off what was once human in him as surplus equipment. "I remember

him telling me," one prostitute he hired later recounted, "that he only made

love to help him write."

Or

look at it in another way. Compare Kendall Taylor's thoroughly competent

biographical account of the Fitzgeralds to the literature Scott distilled from

their life together. "At dinner parties, after falling into a stupor," Taylor

reveals of the summer spent on Long Island, "[Scott] would often crawl under a

table and babble incoherently, or try to eat his soup with a fork." That's good

material, an apt example of Scott's immaturity, his drunken instability, yet it

has no lift, no significance above and beyond the specific. So, describing the

same period in "The Beautiful and Damned" Scott skipped that dumb prank. With

much less, he accomplished far more: "There was an odor of tobacco always --

both of them smoked incessantly; it was in their clothes, their blankets, the

curtains, and the ash-littered carpets. Added to this was the wretched aura of

stale wine, with its inevitable suggestion of beauty gone foul and revelry

remembered in disgust."

Beyond

the intoxicating effect of Fitzgerald's fluency is the vast difference between

his own sophomoric behavior and the brilliant use to which his fiction puts that

drunken era. The accumulation of sordid details is much more than a biographer's

collection of facts and figures, or the raw moment of life itself. The reason

why biographies of Scott and Zelda can't compete with those novels, no matter

how deep the research, is that the Fitzgeralds themselves can't compete.

Of

course, in addition to animating Scott's work, Zelda contributed to the actual

wording on the page. "Plagiarism begins at home," she teased in her review of

"The Beautiful and Damned," and by the publication of "Tender Is the Night" saw

to her horror that, with neither her permission nor her knowledge, Scott had

copied letters she'd sent him from the asylum, to lend greater realism to mad

Nicole Diver. So, here at last is a substantive claim against Fitzgerald the

novelist, a potential case of copyright infringement and certainly grounds for

grammar school detention. As a claim against Scott's art, though, it still

doesn't hold: No matter how much he copied down Zelda's conversation or quoted

without attribution from her letters and diaries, he committed plagiarism only

in fact -- which, contrary to popular opinion, is not a matter of any literary

significance.

Our

poor middlebrow society loathes plagiarism. We hate it with such passion that a

minor instance nearly tarred and feathered the previously unimpeachable

reputation of Martin Luther King. We ought to take a moment, though, to ask why.

We ought to question whether we condemn it just because we're told to do so,

encouraged in print by writers for whom such theft of language matters more than

anything in all the world.

Legally speaking, we ought to be outraged: An author's words are his

intellectual property, as worthy of statutory protection as ownership of an

automobile, say, or a ukulele. For somebody else to use them without permission

and attribution, to kidnap them (as the word plagiary once literally meant) is

to gain unfairly something of value at its author's expense. But that can't

alone account for the degree of our disgust: Had Martin Luther King merely

robbed a bank, his reputation would hardly have suffered so much so many decades

after the fact. Put in other terms, we would still accuse someone of plagiarism

were they, like Fitzgerald, given unrestricted permission to use material not

their own but, again like Fitzgerald, not to provide attribution of the material

used. So our ire isn't merely a healthy legal concern: There also lingers an

anxiety about artistic creation.

Godless as our culture may be, we seem still to believe that books are born as

wholly and independently as Zeus begat Athena. But that's patently false.

Literary creativity isn't truly an act of creation. A writer doesn't manufacture

words. Rather, he chooses them: He chooses to include some and to exclude

others, by those means to kidnap their implications with greater or lesser

precision of phrasing. A writer gives structure to preexisting cultural

associations, finding new meanings by arranging them in previously unimagined

juxtapositions. So it goes with scenes and chapters, an entire book.

We

take for granted that individual words are the building blocks of writing, but

only because most authors adhere to that tradition. Fitzgerald didn't. He wasn't

trying to sneak something by his readers: He jotted Zelda's bon mots in public,

sent a typescript of her diaries to Maxwell Perkins and on his letterhead

ironically titled himself "hack writer and plagiarist." He told people openly

that Zelda was his source for stories such as "The Ice Palace." He didn't mean

by that to offer her credit for his fiction; given his radical notion of

authorship, well ahead of its day, such nonsense would never have occurred to

him.

In the

end, Fitzgerald's unprecedented talent justifies his unorthodox tactics. The

first test of literature is whether the whole is greater than the parts. As

difficult as it is to manipulate the meanings loaded into individual words, to

make literature by arranging whole sentences and paragraphs, to work with

material as full of itself as Zelda's diaries and letters, and to make it

support a whole worldview, is a monumental feat. We already venerate F. Scott

Fitzgerald the wordsmith as even he couldn't have dreamed. Now with more reason

than ever to deplore him as a man and a husband, we equally, astonishingly, have

means to appreciate the sublimation of his wife, her novelty, into art.

About the writer

Jonathon Keats is the author of the novel "The Pathology of Lies." He is

currently at work on a novel about a plagiarist.

Sunday Herald - 25 August 2002

Beautiful

but damned

Sometimes madness is wisdom: Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald, a marriage by Kendall

Taylor (Robson Books, £18.95)

Reviewed by: Lesley McDowell

'IN my next incarnation, I

may not choose again to be the daughter of a famous author,' wrote Scottie

Fitzgerald once, in an introduction to a volume of her father's letters. 'People

who live entirely by the fertility of their imagination are fascinating,

brilliant and often charming but they should be sat next to at dinner parties,

not lived with.'

There are two points here

that Kendall Taylor's authoritative, highly readable and knowledgeable biography

returns to again and again. First is the omission of Scottie's mother, Zelda --

she is the daughter only of a 'famous author' -- which Taylor wants to

counterbalance; the second is the long-fabled impossibility of ever 'living

with' an artist, especially when the artist uses intimate details from that

cohabitation for his or her work.

Had teenage Southern belle

Zelda Sayre merely plumped her bottom down next to the Yankee Princeton student

Scott Fitzgerald, a troubled mind and an even more troubled marriage might not

have resulted. Similarly, a body of literature some consider the greatest

produced in the 20th century might not have resulted either. For Fitzgerald used

his wife's diaries, her mental illness and other intimate details of their

relationship for his books, particularly the character of Daisy in The Great

Gatsby and the Divers' doomed marriage in Tender Is The Night.

It is not controversial that

Fitzgerald did this -- male writers have long utilised the women in their lives

in this way, the most famous perhaps being James Joyce, who fictionalised his

partner Nora Barnacle as Molly Bloom in Ulysses. So what if characters and

scenes in Fitzgerald's fiction came directly out of his marriage? Who cares if

passages from Zelda's diaries were quoted verbatim, unacknowledged and sometimes

without permission? The end result, we are reminded, is genius, and that excuses

everything.

But not according to Taylor,

which is refreshing to hear. Happy to smash that particular myth -- along with

many others, like the one that decrees female madness is sexy rather than

disturbing -- Taylor presents a persuasive argument that says no, using

another's life for the purpose of art is not to be tolerated. In this she

surprisingly has the unwitting support of Fitzgerald himself, who, while happy

to use his marriage and his wife's mental instability for his novels, did all he

could to prevent his wife's own attempt to fictionalise their relationship. When

Zelda did produce her one novel -- Save Me For The Waltz -- about their life

together, Fitzgerald was furious: 'Turning up in a novel signed by my wife as a

somewhat anaemic portrait painter with a few ideas lifted from Clive Bell,

Leger, etc, puts me in an absurd position and Zelda in a ridiculous position. My

God, my books made her a legend and her single intention in this somewhat thin

portrait is to make me a nonentity.'

The 'legend' that Fitzgerald

created was born and brought up in the small Southern town of Montgomery in

Alabama, the youngest of six children. The daughter of a well-respected local

judge, Zelda's place in the local community was high and pretty well

untouchable, even when, along with the Bankhead girls, one of whom, Tallulah,

would later become the famous Hollywood actress, she made a name for herself as

a wild girl who would ride in cars with boys, drink too much at dances and go

skinny-dipping at midnight. The archetypal 'flapper' girl, immortalised in

fiction by Owen Johnson's 1914 novel The Salamander as 'passionately

adventurous, eager and unafraid, neither sure of what she seeks nor conscious of

what forces impel or check her', Zelda knew one thing -- that her life would not

be boring.

Perfectly suited to what

Fitzgerald would term 'the Jazz Age', Zelda would keep her eager suitor hanging

by a thread, dating other men while promising to marry him only when he could

prove that he could afford to keep her. Her fate was sealed when This Side Of

Paradise was published in 1920 and the two married. Their honeymoon quickly set

the pattern of their married life together -- lots of writer friends, lots of

alcohol, lots of fights and lots of being thrown out of hotels.

Fitzgerald was a new media

darling thanks to the success of his first book. Now, married to the carefree,

daredevil Zelda, who matched every one of her husband's drunken excesses with

her own, he became media fodder. Extremes of quiet -- the public needed another

novel, and The Beautiful And The Damned was its reward -- contrasted with

periods of intense party-going as Zelda found marriage to a writer sometimes the

very thing she feared most -- boring and isolating. The birth of her only child

Scottie did not help and within a year or two both had embarked on affairs.

Infidelity was to

characterise their marriage as much as alcohol abuse and it affected Zelda

particularly badly. By 1930, her attempts to find a life for herself apart from

one as Fitzgerald's wife led her to take up ballet, painting and writing. This

last ambition seems to have finished the marriage -- Fitzgerald would not take

on competition from his wife, who was a highly gifted writer, especially not as

his own star seemed to decline. Unable to bear Fitzgerald's discouragement,

Zelda's sanity began to waver and a series of hospitalisations, which was to

last until the end of her life, began. When Tender Is The Night appeared,

detailing Zelda's breakdowns, it seemed to be the last straw.

Throughout her life, Scottie

maintained her distance from her parents, determined not to take part in what

she called the 'tragedy' of their lives. In that term, not only is the sense of

missed opportunities evoked, but also the sense of performance. Zelda Fitzgerald

emerges from this biography somewhat restored to the stage of literary lives,

not merely as the muse of a great writer but as an individual in her own right,

who, given a different set of circumstances, might have achieved a great deal.

One cannot help but think from this account it may have been Fitzgerald's good

fortune to have married Zelda Sayre; it was perhaps her misfortune to have

married him.

Was 'mad'

Zelda really just too great a rival for Scott?

Vanessa Thorpe, arts and

media correspondent

Sunday September 22, 2002

The Observer

She was a socialite who fell

apart in the glare of transatlantic publicity, her apparent madness blamed for

bringing down her genius husband. But now a British biography of Zelda

Fitzgerald is to challenge the image of her as a wilful, privileged lunatic who

hindered the work of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Research by

Sally Cline, a Cambridge University and University of East Anglia academic, has

uncovered a story of misdiagnosis, marital oppression and sanctioned medical

poisoning. 'Zelda has always been represented as the mad wife,' Cline said. 'But

she suffered as much from the treatment as the illness itself.'

After

talking to surviving doctors and friends and looking at previously sealed

medical notes, Cline has put together a story of creative rivalry and physical

cruelty. Fitzgerald immortalised his Southern Belle bride in The Great Gatsby

and Tender is the Night, while at the same time refusing to remove her from

hospital. He argued she would disrupt his writing.

When the

glittering couple married in 1920, Zelda made the gossip columns by jumping into

the fountain in New York's Washington Square. She was already renowned for

dancing on tables and cartwheeling in hotel lobbies.

Dubbed the

'first American flapper' by her husband, she was a talented artist and dancer

who wanted to write novels. But as his drinking worsened and her mental

stability faltered, she was banned from dancing, then from writing. 'One

psychiatrist thought they should be treated together,' said Cline. 'But

Fitzgerald would not agree to this diagnosis of folie à deux . He forbade her

from writing about their life, even insisting publishers cut large sections from

her book, Save the Last Waltz, that covered the same ground as his own

work-in-progress, Tender is the Night.' He also suggested her articles be

printed under both their names, or just his.

Cline

maintains Zelda never suffered from writer's block. 'Instead she fought the

block on her writing imposed by a fellow writer.'

Zelda's

unfinished second novel, Caesar's Things, is now about to be published, while

her startling paintings are to go on show in America, Paris and London. Cline

predicts an artistic reappraisal. She believes Fitzgerald used his wife's

illness as an excuse for drinking. At first she was referred to as 'eccentric',

then as 'mentally disordered', then as 'schizophrenic'. Yet, Cline argues, she

produced her best work as a writer, dancer and artist during her time in and out

of hospitals.

Writing from

inside one institution, Zelda complained to her alcoholic husband: 'You blamed

me when the servants were bad, and expected me to instil into them a proper

respect for a man they saw morning after morning asleep in his clothes.'

Her most

desperate letters were reproduced in Tender is the Night, when Nicole writes to

Dick Diver: 'I am completely broken and humiliated, if that was what they

wanted. I have had enough and it is simply ruining my health and wasting my time

pretending that what is the matter with my head is curable.'

Fitzgerald

was defended by friends such as Ernest Hemingway and John dos Passos, who said

he was trying to 'do the best possible thing for Zelda, to handle his drinking

and keep a flow of stories into the magazines to raise the enormous sums Zelda's

illness cost'. Anxiety attacks, eczema and lesbian infatuations were all cited

as evidence of Zelda's schizophrenia by Dr Eugen Bleuler, the Swiss psychiatrist

who first coined the term. Yet Dr Irving Pine, the last psychiatrist to treat

her, told Cline he felt Zelda was consistently misdiagnosed. 'He disputed the

label "schizophrenia" and suggested that psychiatrists had failed to take her

talents seriously,' writes Cline. 'Bleuler saw her as a woman competing publicly

with her more famous husband in an inappropriate manner.'

Zelda was

heavily drugged and given insulin and electric shock treatments for years. On

her occasional outings, she continued to behave erratically, once stripping

naked during a game of tennis before being carried away screaming by hospital

attendants. In 1948, eight years after her husband's death, she was killed in a

fire at a mental hospital.

LRB |

Vol. 25 No. 12 dated 19 June

2003 |

Nina Auerbach

Vampire to

Victim

Nina

Auerbach

Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in

Paradise

by Sally Cline | John Murray, 492 pp, £25.00

Zelda Fitzgerald would probably

call herself a post-feminist today, but when she was alive, she made herself a

flapper. In 1926, F. Scott Fitzgerald's charmingly wild wife told an interviewer

that she hoped her daughter's generation would be even 'jazzier' than her own:

'I think a woman gets more happiness out of being gay, light-hearted,

unconventional, mistress of her own fate, than out of a career that calls for

hard work, intellectual pessimism and loneliness. I don't want Pat to be a

genius, I want her to be a flapper, because flappers are brave and gay and

beautiful.'

Did Zelda really say all this?

So many creeds have been thrust on her by adoring Pygmalions, from Scott

Fitzgerald himself to Sally Cline in this passionately partisan biography, that

the real Zelda long ago drowned in images, including her own. Still, if she did

not shower these particular scintillating adjectives on her flapper-self, her

life proclaimed them.

A flapper in the 1920s, like a

post-feminist today, hovers between defiance and compliance. She embraces the

subordination the previous generation fled, but calls it 'brave and gay and

beautiful', not self-sacrificial or boring. Because Zelda thought work was

depressing as well as desirable, she is not my favourite biographical subject:

she reminds me too much of my younger colleagues, who find it grim to buck the

systems of profession and family it was so elating in the 1970s to defy. Unlike

my own female heroes, Zelda never defined herself; she just flailed about under

the aegis of her brilliant husband. As a girl, she did everything she was

supposed to do: she was a Southern belle who married a dapper genius once he

became rich enough to keep her. Until money and energy ran out, they lived the

media-starred life of Beautiful People in New York and Paris, drowning

domesticity (and, almost, their stoical daughter) in servants, fun and

champagne.

Belatedly, Zelda saw that she

was patronised as a tart-tongued appendage to glittering Scott. Jealous of his

fame, she snatched at a career, but not in the frumpy way 'that calls for hard

work, intellectual pessimism and loneliness'. She flung herself into three arts

simultaneously - ballet, painting and writing - with such ferocity that she

plummeted into the madness that consumed her last 18 years, most of which were

spent in mental hospitals and, finally, under the suffocating surveillance of

the Alabama family from which Scott had been her escape.

Zelda lived to please, but

nobody much liked her. Ernest Hemingway, who detested women writers, saw her as

an insane harpy who destroyed Scott's work. Though Cline insists, often on

flimsy evidence, that Zelda was an authentic artist, she is fair-minded enough

to surround her with women who really did make their careers on their own:

Rebecca West, Dorothy Parker,

Natalie Barney and Zelda's Montgomery classmate

and friend Sara Haardt, who fled belle-dom to write fiction; the serious and

tubercular Sara eventually married H.L. Mencken and died shortly afterwards.

These women were more or less kind to Zelda (Dorothy Parker bought two of her

drawings in 1934, though she found them too tortured to hang), but she was not

their peer. She may have been too angry for Hemingway, but she was too wifely

for professional writers.

Yet in 1970 Zelda's life, not

the careers of her successful contemporaries, became, potentially, our own.

Nancy Milford's extraordinary biography gripped and chilled young literary women

in America. I still recall the shock of her book, though as a Scott Fitzgerald

fan I had thought I knew the story: the fame, the fun, the crash, the crack-up,

the hospitals, the drain of money and love, and the ignominious trapped deaths -

for him in the waste of Hollywood in 1940, for her in an asylum fire eight years

later. Smart, stylish, funny, unmoored, Zelda had always seemed the figurehead

of a lost generation, but in 1970 she became the symbol of lost women.

It had never occurred to me that

Zelda Fitzgerald had a life outside her husband's lyrical prose. Of course women

writers had lives, but did wives? Did they need them? Milford's revelation,

which shouldn't have been a shock, was that Zelda had lived outside Scott's

metaphors. In fact, his images of a shimmering golden girl, who in the great

novels Gatsby and Tender Is the Night becomes something like a

vampire, entangled Zelda in his fantasies; so did the role of wife itself.

Pillaging her letters, her journals, her language (it was supposedly Zelda who

said, at her daughter's birth: 'I hope it's beautiful and a fool - a beautiful

little fool,' a blessing/curse with which Scott would pinion Daisy Buchanan in

Gatsby), Scott did not glorify Zelda, but, according to Milford, drained

her incipient identity.

Scott Fitzgerald was most

women's favourite Modernist, as Keats was our favourite Romantic, especially

compared to myopic, preening Wordsworth. Compared to his sometime friend, the

posturing bully Hemingway, Fitzgerald seemed gentle, almost girlish,

breathlessly embracing his charmed fictional world. But Milford showed us

another Fitzgerald face, one that appeared when his wife began to write.

In the traditional reading of

her life, Zelda's belated lunge at art (she was 27 when she threw herself into

dancing) was a symptom of insanity. In hospital, she wrote, in an astonishing

three weeks, her autobiographical novel Save Me the Waltz. Scott,

labouring for years over Tender Is the Night and transcribing his wife's

symptoms into its mad heroine, exploded when he read Zelda's first draft. He

claimed that she had stolen his material (her own life) and made him look like a

weak fool (in the first draft, Zelda named the ineffectual husband Amory Blaine,

the glamorous hero of Scott's bestseller This Side of Paradise).

Save Me the Waltz

is in fact vividly different from Scott's work. For Zelda, marriage is a shadowy

affair: the novel springs to life in ballet school, a female world of muscles,

sweat, competition and community. Unlike Scott, intoxicated by hazy images,

Zelda lives in bodies and smells. 'Do you still smell of pencils and sometimes

of tweed?' she wrote longingly to Scott from hospital. Perhaps because he

thought his wife was stealing his material, or perhaps because she had access to

a tactile world beyond his, Scott did his hysterical best to enlist Zelda's

psychiatrists in suppressing not only her novel, but all her artistic

aspirations. His collusion with her doctors in a ghastly attempt to 're-educate'

Zelda into wifehood was, for me, the shocking centre of Milford's book. Mad

Zelda went from vampire to victim, lovable Scott from victim to oppressor. Like

the wife in Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1892 story 'The Yellow Wallpaper,' which

was reprinted around the same time

Milford's biography appeared, Zelda Fitzgerald was broken by an

alliance among those quintessential good men, husbands and doctors.

Milford's biography is saved from polemic by its grace and tact.

Her own commentary is spare; most of the story is told in irresistible letters,

by the principals and the many writers in their circle, so that the dynamic of a

wife's wreck becomes irrefutable, not imposed.

Milford never denies that Zelda

was ill as well as insulted. Scott is allowed his agony, romantic, creative and

financial. Zelda's story remains the one we knew, but told from a viewpoint that

restores the life she experienced.

After Milford's achievement,

does Zelda Fitzgerald need another biography? I don't think so, though Sally

Cline's account is lush and readable, with some telling new material. Cline,

whose last book was a biography of Radclyffe Hall, gives full and fascinating

accounts of the Fitzgeralds' fraught relations with the homosexual community in

bohemian Paris. We knew of the paranoid obsession with 'fairies' that terrorised

Hemingway, Zelda and Scott himself (for Fitzgerald, some evil homosexual

abstraction, not competitive tension, killed his friendship with Hemingway: 'I

really loved him, but of course it wore out like a love affair. The fairies have

spoiled all that'). But Zelda's undefined association with the lesbian community

of Romaine Brooks, Natalie Barney and

Djuna Barnes, her insistence during her

first breakdown that she was in love with Barney, and also with her ballet

teacher Lubov Egorova, are new to me. The obsessed Fitzgeralds, flayed with a

terror of desires that were beyond the pale, present a touching picture of

American innocents abroad, and also of the tortured artistic generation that

came of age after Oscar Wilde's trials in 1895. Adultery, of course, remained

not sick but sophisticated: Scott had a series of affairs. She also itemises his

alcoholic binges, whose details more reverent biographers want to forget. Cline

places her characters in a tougher, less glamorous world than we are used to.

Still, her advocacy of Zelda is

overwrought. Cline has written the sort of adoring biography Zelda herself might

have conceived. Its subtitle, 'Her Voice in Paradise', has a double meaning. On

the surface, of course, it echoes ironically the title of Scott's famous first

novel, This Side of Paradise, but there is a Spiritualist dimension as

well, evoking a glorified Zelda dictating from the afterlife. Cline's Zelda is

so brilliant, so conspired against, ultimately so triumphant, that her life

loses its contours.

For one thing, the quotations

from the Fitzgeralds' letters and journals that Cline uses are so truncated - no

doubt because many others have already published this material - that she seems

to be forcing a story rather than letting one unfold. From the harrowing series

of letters that follow Zelda's early hospitalisations, in which Scott rages

about her stealing his material and she tries to mollify him, Cline quotes the

following snippets:

Scott could not contain himself.

'So you are taking my material, is that right?'

'Is that your material?' Zelda

asked. The asylums? The madness? The terrors? Were they yours? Funny, she hadn't

noticed.

It takes a sharp reader to

notice that the final five accusatory sentences are Cline's, not Zelda's, as if

Cline were now the medium through which her subject vindicates herself.

Cline's Scott is an unmitigated

villain. She insinuates vast conspiracies, not typical sexist ignorance, in

Scott's and the doctors' assumption that Zelda's ambition and her sexuality were

symptoms of insanity. She is equally conspiratorial about Zelda's misdiagnosis

as a schizophrenic. Scott did not invent his times: until quite recently,

'schizophrenic' was indeed a catch-all category for mental illness; throughout

most of the 20th century, it was a commonplace that ambitious, sexually driven

women were, by definition, mad.

Today, Zelda would no doubt be

diagnosed as a manic depressive (hence her frenzied bouts of creative fever,

followed by weeks of silence and withdrawal); she would probably have responded

to lithium, a drug that was not used until the 1970s. Scott was no more

responsible for medical ignorance than H.L. Mencken was responsible for Sara

Haardt's early death from tuberculosis. In fact, out of the welter of Scott's

laments and accusations comes some prophetic sense: 'I can't help clinging to

the idea that some essential physical things like salt or iron or semen or some

unguessed at holy water is either missing or is present in too great quantity.'

Psychopharmacology has discovered the truth in Scott's wild guess, but Zelda is

not the only hectored patient who might have been cured had she been born later.

Cline accuses Fitzgerald of

out-and-out plagiarism in his literary use of Zelda's material. This is a shaky

charge: before our own litigious days, writers were licensed sponges. Moreover,

we would lose voices like Dickens's, Sylvia Plath's and Philip Roth's if their

pillaged intimates had the right of censorship. Scott did publish some of

Zelda's stories under his own name, as Milford showed, but they might not

otherwise have been published at all. Zelda's achievement as a writer is not

brilliant. Save Me the Waltz, her one published novel, is often violently

alive, but it is also patchy and disconnected. When it appeared, it sold almost

no copies. Her unfinished novel, Caesar's Things, and her long play,

Scandalabra, sound barely coherent. Cline puts an angry caption under a

photograph of Sara Haardt: 'Sara always received more encouragement from her

husband H.L. Mencken than Zelda did from Scott.' But Haardt was a professional

writer long before she met Mencken. Finally, writers write their own careers.

Encouragers are incidental.

For all his overbearing

accusations, Scott seems to have helped as much as he impeded. In the early

days, Zelda was glad enough to use Scott Fitzgerald's name to promote her

stories; his editor Max Perkins handled a slightly cut version of Save Me the

Waltz; Scott tried tirelessly to edit the welter of Scandalabra into

a presentable shape. His friends loyally attended Zelda's art shows and bought

her paintings; after his death, she exhibited in Montgomery, where, thanks to

Scott, she was something of a local celebrity. But even before her illnesses,

she made few attempts to strike out on her own.

Zelda was always on the verge of

an independent identity she never embraced. In 1929, a ballet company in

Naples invited her to join it as a soloist: she turned down the

job and shortly afterwards became a professional invalid. In a vivid section of

Save Me the Waltz, the heroine does go to

Naples, not just as a soloist,

but as the prima ballerina in

Swan

Lake. She is lonely

and adrift. When her snooty daughter visits, she is embarrassed by her relative

poverty. Naples sickens the child; both the girl and the dancing mother are

relieved when she returns to her father. Shortly thereafter, as if in

punishment, an infected foot ensures that the heroine will never dance again.

Instead of living out this dark dream, even finding within it a possible happy

ending, Zelda cracked up.

The Naples invitation makes

nonsense of the condescending assumption that Zelda's dancing was a pathetic

symptom, not a vocation, but her refusal to follow through was, I think, the

turning point of her life. Cline does her best to blame Scott for this failure

of nerve with the vague suggestion that he somehow hypnotised his wife: Zelda's

'strange passivity at this critical moment implies an emotional fatigue from

many months of professional subservience'. But if Zelda had wanted to go to

Naples, her husband could have stopped her only by locking her in the closet. By

that time, I suspect, he would have been relieved - and freer to work - had

Zelda begun to make a career on her own. But she shrank from an opportunity she

associated with 'hard work, intellectual pessimism and loneliness'. One can

blame something amorphous, such as 'the backlash' or 'the times' or whatever

else might brainwash young women into associating careers with deprivation

rather than challenge and power and fun, but it's unreasonable to blame

Fitzgerald for depriving his wife of a chance she refused to take.

I hope it isn't reverting to the

old 'angelic Scott, demonic Zelda' stereotype to grant Zelda Fitzgerald the

power of all women to create her own failures as well as to endure them.

Moreover, Cline seems to see no failures in Zelda's three truncated careers. Not

only does she enthusiastically insist on her talent at all three - about which

she is surely right - but she also makes grandiose claims I find ridiculous. She

solemnly compares Zelda's prose to Faulkner's (as well as Scott's), her

paintings to those of Picasso, O'Keefe and Van Gogh. Is Zelda really on a par

with them, or is she flailing around for a style of her own? Since Cline

reproduces only a handful of her paintings, referring the reader to others (her

mother destroyed most of them after her death), we must take her achievement on

faith. Cline does reproduce Zelda's unused jacket design for The Beautiful

and Damned, in which a naked Zelda looks pertly out of a glass of champagne.

It's cute, but it looks less like a book jacket than an invitation to a party.

The late flower paintings, which Brendan Gill provocatively called 'the

expression of a violent, undischarged rage' and thus 'radically unsuited to the

New Yorker', sound intriguing, but they might be better read about than

seen.

One of Scott Fitzgerald's

cruellest remarks is also one of his truest: 'Now the difference between the

professional and the amateur is something that is awfully hard to analyse, it is

awfully intangible. It just means the keen equipment; it means a scent, a smell

of the future in one line.' Zelda could smell bodies, but she did not have the

scent of the professional. In Victorian England, her trio of talents would have

been cooed over as 'accomplishments'; in all times, women are loved for

remaining amateurs. It was Zelda's tragic flaw, not the fault of any man, that

she would not take the leap into professionalism.

Instead, she became a

professional patient, and thereby lost both husband and career. Cline tries to

decorate these losses with Wagnerian triumphal strains: while Milford titled the

section depicting Zelda's first hospitalisations 'Breakdown', Cline calls it

'Creative Voices'. Milford designated Zelda's last drifting years as Scott's

widow, spent largely in her mother's custody, 'Going Home'; Cline calls it 'In

Her Own Voice'. We all would like Zelda Fitzgerald to have ended in feminist

triumph, but Milford's

sad, simple words seem to be more appropriate to her lost life. Cline's

rhetorical elation makes me nervous about our own times. In thirty years Zelda

Fitzgerald has gone from case history to cult figure. The life of this wrecked

if gallant woman has become, not the cautionary tale it was in 1970, but an

achievement to applaud.

Nina Auerbach

teaches at the University of

Pennsylvania.

Her study of Daphne du Maurier is out in paperback.

| |

|

The Women’s Review of Books

|

|

|

|

OCTOBER 2003

Zelda comes into her

own

Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline. New York: Arcade,

2002, 492 pp., $27.95 hardcover.

Reviewed by

Nancy Gray

ONE OF THE MOST

ENDURING, and romanticized, images we have of early 20th-century art and culture

is that of the Jazz Age. Consider the artists, writers, and dancers whose works

we continue to revere. Think of the stories and exploits, the heady tales of

living high and dying young, the image of expatriates squeezing every last drop

of experience out of the years between the two world wars. There in the midst of

it all is Zelda Fitzgerald, icon extraordinaire--a Southern belle married to one

of the most celebrated writers of her day, the flapper who jumped into fountains

and got her picture in the papers, the woman who had it all and then went

famously mad. Her story is paradigmatic of the era, or at least it has seemed

so. And it is here, in the tensions between what seems and what is, that

biographer Sally Cline has found her richest material. Her aim is to set the

record straight, "to give Zelda a life of her own," separate from as well as

intertwined with Scott Fitzgerald's and their "golden couple" image. The

structuring device Cline has chosen for this task is that of voice: Each of the

book's six parts is structured around the "voices" that shaped Zelda's life,

culminating in "her own voice." By that Cline means above all Zelda as artist,

the aspect she feels has been most neglected by other biographers in favor of

the more mythic Zelda.

Though the

Fitzgeralds themselves wrote repeatedly about the costly underside of

maintaining their glamorously troubled image, that image has persisted--largely,

according to Cline, because Fitzgerald biographers have insisted on it. Cline's

book is quite another matter. It's possible to come away from it feeling as if

you know Zelda and Scott too well. Her access to published and unpublished

letters, journals, manuscripts, institutional records, library archives, and

people who knew or were related to Zelda is extensive, frequently going beyond

that available to previous biographers. She digs carefully and relentlessly into

the details behind competing or incomplete accounts, noting that even some of

her interviewees who knew Zelda "found it hard to distinguish between their

memories and their readings of what has become an abundance of Fitzgerald

material." Cline manages to make the distinctions sharp while recognizing the

connections, even the collusion, between fiction and reality in Zelda's life.

What emerges is a scrupulously researched account of a woman who was always in

the limelight yet was ill-equipped either to deal with it or to do without it, a

complex mixture of Southern belle, Jazz Age wild child, wife, mother, and

seriously ambitious artist. Cline gives us a Zelda of contradictions, a woman

"both intensely private and publicly outrageous," whose competing sensibilities

overwhelmed her as much as they fed her creativity. As Zelda's life with Scott

moves from high adventure to bitterness, rivalry, jealousy, and illness, she

seems undone by having no solid foundation to hold onto. In the end, her story

reads as tragedy, her death a needless waste, leaving one wondering what she

might have accomplished had things been otherwise.

One of the more

fascinating aspects of Cline's approach is her liberal use of fiction as

evidence for fact. Her reason for doing so is persuasive:

Zelda and Scott

flourished as capricious, merciless self-historians, writing and rewriting their

exploits. They used their stormy partnership as a basis for fiction, which

subsequently became a form of private communication that allowed fiction to

stand as a method of discourse about their marriage. (pp. 1-2)

For them, Cline

says, "imagination was always more powerful than fact." Nowhere is this issue

more evident than in Cline's account of the debates over Zelda's role in Scott's

writing. While for the most part Cline takes an even-handed view of these two

difficult personalities, her focus on what Zelda lost along the way is (perhaps

inevitably) marked by impatience, if not anger, with Scott's part in it. She

points out, for instance, that what Scott's biographers refer to in his work as

"inspired by" Zelda's letters and remarks was in fact, "not a matter of

'inspiration' but a direct borrowing of Zelda's lines." She debunks Zelda's

supposed acquiescence, reinforcing Zelda's public quip that Scott "seems to

believe that plagiarism begins at home" with detailed examples of Zelda's

crossing out of Scott's name on story manuscripts and replacing it with her own,

or inserting "No!" and "Me" where he used her words as his own. Cline duly

revisits the well-known example of Scott's insistence that Zelda remove large

passages from her novel Save Me the Waltz (written while he was

struggling to complete Tender Is the Night) as they, in his view, usurped

his literary right to their shared experiences. Referring to Zelda's original

manuscript and draft revisions as "mislaid," Cline points out that while there

is no direct evidence of what deletions Zelda actually made, Zelda firmly

insisted in a letter to Scott that she would revise strictly "on an aesthetic

basis." Cline uses the incident to demonstrate Zelda's determination to be an

artist in her own right and to stand up to Scott in the process.

WRITING IS ONLY ONE

of Zelda's "three arts"; the other two are dancing and painting. Zelda's

determination to train, at the late age of 27, to be a ballet dancer and her

remarkable if limited success, are already well known. Most of Cline's material

here will be familiar enough; but her interpretation of the effects of Zelda's

commitment to her teacher, Madame Egorova, are worth noting. Both Zelda's

doctors and her husband blamed her first breakdown on her "obsession" with

dancing. Dancing, however, was the least of it, according to Cline. Zelda's

devotion to Egorova was, in Scott's view, "abnormal," and became the basis for

his accusations that she had lesbian relationships. While this may have been so

while Zelda was hospitalized, Cline believes that Zelda's commitment to dancing

had more to do with Zelda's desire to become independent of Scott and his need

to control her. Cline covers a good deal of ground here, teasing out and

correcting suppositions about their affairs; their attitudes toward sexuality

(both of them more or less "bisexual" in manner and appearance, but he loudly

homophobic, she speaking in terms of "desire"); their talk of divorce; Zelda's

suicide attempts; and the varying states of her mental health. Cline links

Scott's frantic disapproval of Zelda's dancing and his obsessive control of her

writing to Zelda's increasingly frustrated and erratic behavior. She contends

that Zelda's arts came most fully to the fore between 1929 and 1934, the period

of her first breakdowns and hospitalizations, and suggests that art was Zelda's

lifeline in her struggle to hang onto a sense of self and sanity as her life

fell apart. Wistfully evoking a mythical ability to live in fire, Zelda wrote,

"I believed I was a Salamander, and it seems I am nothing but an impediment."

But as an artist she was a self with vision and passion of her own.

Interestingly

enough, while most of Zelda's doctors agreed with Scott that Zelda's writing and

dancing were signs of her instability, they referred to her painting as

"therapeutic." From Cline's descriptions of the paintings, as well as from the

one reproduced on the book jacket (Ballerinas Dressing), it's clear that

Zelda was not at all interested in depicting typical feminine forms. Yet her

painting may have been accepted because it was seen as a less serious threat

than writing or dancing to Scott's work and his status as her husband-protector.

Cline regards painting as central to Zelda as a person and as an artist, as well

as the art most in need of reclaiming on Zelda's behalf. She speculates that

early biographers paid scant attention to it because so much of it was lost or

destroyed. But Cline was able to see more than two-thirds of the paintings

themselves (held mostly in private collections) and slides of the rest. Citing

Zelda's visual art as "the most successfully refined of her three gifts," she

examines the work Zelda produced from 1925 until her death in 1948. She

interprets Zelda's technique, influences, recurrent themes, and productivity as

proof of talent and as a rich source of clues about the artist behind the work.

For instance, she is able to counter views of Zelda as an indifferent mother by

examining the paper dolls Zelda created to delight and instruct her daughter

Scottie. The hours spent painting and playing with the hundreds of fairy-tale

scenes attest to Zelda's parental attentiveness. In addition, Cline looks at the

characters Zelda dressed in multiple and unexpected personas as examples of her

nonconformist sensibilities: "Though Zelda is partly making children's art for

Scottie," Cline says, "she is at the same time subverting the conventional

childhood approach by using dolls to transgress male/female boundaries." Cline

argues that Zelda's unconventional vision, present in all aspects of her life,

was most fully realized in her visual arts. In her view, painting stands as

Zelda's greatest claim to being an artist in her own right. And because Zelda

continued to develop this art so assiduously right to the end, Cline uses it,

along with a careful study of hospital records, to correct previous depictions

of Zelda during the eight years after Scott's death as hopelessly lost in

madness.

Between 1930 and

1948, Zelda resided for varying lengths of time in seven mental clinics on two

continents. She was diagnosed as schizophrenic--though her last psychiatrist

told Cline that manic-depression was more likely the case--and subjected to a

remarkable array of debilitating treatments. Until Scott died in 1940, he was

intimately involved with Zelda's treatment as well as financially responsible

for it. Cline sees his role as reflecting his need to see himself as "a junior

consultant almost on a par with her doctors," who knew better than anyone else

what was best for Zelda. Cline's tone becomes one of increasing indignation as

she traces Zelda's experience with "madness" (the quotation marks are hers.)

Criticizing Scott and the medical establishment for doing as much harm as good,

she details treatments aimed at "reinterpreting" Zelda's behavior as

"disappointed ambition" inappropriate to a wife, and "reeducating" her "toward

femininity, good mothering and the revaluing of marriage and domesticity." Cline

makes the case that Zelda's illness was at least in part a response to feeling

invisible and trapped, and that her art constituted a viable attempt to break

free of the roles in which she was cast.

Cline's last

chapter is devoted primarily to countering the "overwhelmingly powerful myth" of

Zelda as a "left-over widow" who, when not hospitalized, wandered the streets

"lugging her Bible on a one-woman mission to convert the residents." Instead she

shows Zelda living quite competently on her own in Asheville, North Carolina,

checking herself in and out of Highland Hospital as needed and approaching life

with a good deal of "clarity, healthy activity, above all enormous creative