12-11-2004

THOM GUNN

(1929 - 2004)

POEMS:

The Hug

Obituary

Thom Gunn

Gifted poet who explored the balance of life's contradictions

Neil

Powell

Wednesday April 28, 2004

The Guardian

In a poem from his 1982 collection The Passages Of Joy, Thom Gunn, who has died aged 74, delightedly announced: "I like loud music, bars, and boisterous men." But he immediately provided a characteristically cerebral explanation: these were things "That help me if not lose then leave behind,/ What else, the self."

This relationship - a balance rather than a conflict - between the body's hedonism and the mind's discipline was a central, enduring theme in the work of one of the late 20th century's finest poets.

The "Thom" was not an affectation, but was short for Thomson, his mother's maiden name. He was born in Gravesend, Kent, and his mother, who died when he was 15, had been a literary journalist; his father became editor of the Daily Sketch.

His adolescence, spent in north London, apart from a brief evacuation to Hampshire, coincided with the second world war. He was educated at University College school, and by the time he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, after two years' national service, he was 21. His first book, Fighting Terms (1954), contained poems written while he was an undergraduate: they engagingly combined youthful brashness with scholarly allusiveness.

Two Cambridge friends were especially influential: Tony White, an actor who "dropped out, coolly and deliberately, from the life of applause", and Mike Kitay, an American who was to become for Gunn "the leading influence on my life, and thus on my poetry". It was primarily to be with Kitay, his lifelong partner, that Gunn applied for a creative writing fellowship at Stanford University, California, which he was awarded in 1954 and where he worked with the great, if wayward, poet-critic Yvor Winters.

The juxtaposition of Gunn's metaphysical Englishness with Californian life and Winters' teaching is very evident in his second collection, The Sense Of Movement (1957), an exciting, deliberately provocative book whose distinctive energy comes from an apparent tension between form and content: traditional poetic structures and intellectual abstraction are deployed on subjects that include Hell's Angels, Elvis Presley, and a keyhole-voyeur in a hotel corridor.

It is no accident that the book's most celebrated poem, On The Move, borrows its epigraph (Man, you gotta Go) from the Marlon Brando film, The Wild One.

From 1960 onwards, Gunn lived in San Francisco, for some years lecturing at the University of California at Berkeley. His third book, My Sad Captains (1961), is divided into two distinct halves: it appears, superficially, to be a contrast between Englishness and Americanness, for the magnificent opening poem, In Santa Maria Del Popolo, looks back to Europe as surely as Waking In A Newly-Built House, which begins Part II, looks forward to America.

But the distinction is, in fact, a technical one, between closed metrical forms and open syllabic ones, and it reflects an emotional and philosophical, rather than a geographical, division: quiet understatement replaces the seemingly aggressive stance of earlier poems.

During the early 1960s, Gunn worked on two extended projects: the long poem Misanthropos, completed in London in 1964-65, about a man who thinks himself the sole survivor of the ultimate global war; and a book-length sequence of free-verse captions to photographs by his brother Ander, published as Positives (1966).

The discipline of writing to a specific set of visual images and the liberation of free verse were both beneficial to Gunn: a poem such as Pierce Street in his next collection, Touch (1967), has a grainy, photographic fidelity, while the title-poem uses hesitant, sinuous free verse to portray a scene of newly acknowledged intimacy shared with his sleeping lover (and the cat).

By now, Gunn's earlier aggressive-defensive mode had given way to a more open, flexible stance; and he was in the right place at the right time - San Francisco in the late 1960s - to explore this openness.

These, he said, "were the fullest years of my life, crowded with discovery both inner and outer", and the poems written then make up his most sunlit, celebratory book, Moly (1971); rock music and drug-induced euphoria find their characteristic counterbalance in the beautifully resonant lucidity of The Fair In The Woods, Grasses and Sunlight.

However, in Gunn's next book, Jack Straw's Castle (1976), the dream modulates into nightmare, related partly to his actual anxiety-dreams about moving house, and partly to the changing American political climate. "But my life," he wrote, "insists on continuities - between America and England, between free verse and metre, between vision and everyday consciousness."

The Passages Of Joy reaffirmed those continuities: it contains sequences about London in 1964-65 and about time spent in New York in 1970; its forms range from very supple free verse to an excellent sonnet; dream and nightmare are largely subsumed in the cool, anecdotal observation towards which he had been moving in the 1960s. The Occasions Of Poetry, a selection of his essays and introductions, appeared at the same time.

Ten years were to pass before his next collection, The Man With Night Sweats (1992): here, with terrible irony, the poet who had sought to lose "the self" found himself "less defined" and "unsupported" as his self-defining friends died of Aids. Much of the book is tersely occasional, but in its final 30 pages Gunn used the context of Aids to produce major poems about mutability and mortality, endurance and celebration.

In 1993, Gunn published a second collection of occasional essays, Shelf Life, and his substantial Collected Poems, which usefully reintegrated a number of previously fugitive pieces into the main body of his work. His final book, Boss Cupid (2000), ranges from reckless youth to elegiac age; from gossipy anecdotes to movingly meditative poems such as In The Post Office, in which he finds himself a "survivor" who "may later read/ Of what has happened, whether between sheets,/ Or in post offices, or on the streets." One could hardly ask for more.

Thomson William 'Thom' Gunn, poet, born August 29 1929; died April 25 2004

LINKS:

Study guide on the poetry of Thom Gunn

Thom Gunn -- poet of the odd man out

Wednesday, April

28, 2004

Thom Gunn, the British-born poet who made San Francisco his home for 40 years, and wrote poems that combined mastery of form with a contemporary frankness and subject matter, died Sunday night in San Francisco. He was 74.

Mr. Gunn died in his sleep at home and was discovered at 9 p.m., said his partner of 52 years, Mike Kitay. "I'm thinking it was probably a heart attack, " Kitay said, "but the medical examiner won't know the cause of death for weeks."

Members of the literary community reacted yesterday with shock at Mr. Gunn's sudden death. "I thought he was possibly the best living poet in English," said Wendy Lesser, an author and editor of the literary journal the Threepenny Review. "Unlike most poets, he was equally at home in rhyme and non- rhyme, in free verse and patterned rhythms. He had a quiet, modest, almost impersonal voice as a poet, but every poem he wrote was recognizably his -- and his poems about death, particularly about deaths from AIDS, are masterpieces."

Robert Pinsky, a former U.S. poet laureate and professor at Boston University, e-mailed his thoughts on Mr. Gunn from Berlin: "His poems attain a cool clarity, an ability to be morally discerning but not judgmental; amused but engaged." By doing so, Pinsky said, they "reflect the man's generosity of spirit; his wickedly funny but forgiving skepticism about literary fashions and blowhard academic critics; his kind acceptance of many kinds of people."

"There was a special quality that had to do with the underside of life," said poet Philip Levine. "The characters who walked through Thom's poems -- they were everybody. He had such an affinity for the odd man out, the non- belonger, the despised, the downtrodden. He had this sympathy and insight, and he really humanized these people and made them loveable in his poems."

Vital and spry and endlessly youthful, "looking less like a retired professor than an emeritus rock-star" as a local critic wrote, Mr. Gunn was an enthusiastic advocate of his adopted city and shared a shingled home in Cole Valley that he bought in 1971 with a $3,300 down payment.

From 1958 to 1966 and from 1973 to 1990 he taught at UC Berkeley, commuting by bus. But he gave up a tenured position because he couldn't bear to attend department meetings.

Mr. Gunn was the recipient of many literary awards -- the Forward Prize, England's largest poetry prize, in 1992; a $369,000 MacArthur Fellowship for lifetime achievement in poetry, in 1993; and last year the prestigious David Cohen British Literature Prize -- but he assiduously rejected the stuffy attitudes and behaviors of academia.

In spirit, Kitay said, he remained an "outlaw." He wore leather when he lectured at Cal, identified with biker culture (and briefly owned a motorcycle), tried LSD, wrote poems extolling the gay bathhouse culture of the '70s and was an avid fan of "The Simpsons," "NYPD Blue" and "Friends." He disliked snob-constructed divisions separating "high culture" from "low culture."

"He was always proud, as I was, that we would go hear the Grateful Dead play in Golden Gate Park. We loved all that," said Kitay. He was a displaced Englishman "of decorous, skillful, metrical verse," wrote the young English poet Glyn Maxwell, "who had for his own reasons become absorbed into an alien culture that gave him alien subjects (like sex), alien backdrops (like sunshine) and, most vexing of all, made his forms melt on the page."

Mr. Gunn was born in Gravesend, England, on Aug. 29, 1929. His father, Herbert, was a Scottish merchant seaman who became a journalist. His mother, Ann Charlotte, also a journalist, was an independent spirit who encouraged Mr. Gunn's writing.

In an interview, Mr. Gunn said his parents divorced when he was 8 or 9. His mother, to whom he was close, committed suicide when he was 15. He and his younger brother, Ander, found the body, but Mr. Gunn wasn't able to write about it until 1992, in the poem "The Gas-poker."

Forty-eight years ago

-- Can it be forty-eight

Since then? -- they forced the door

Which she had barricaded

With a full bureau's weight

Lest anyone find, as they did,

What she had blocked it for.

Mr. Gunn studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating in 1953. He was an early success, recognized by the critical press as part of "The Movement," a group of poets including Philip Larkin, Kinglsey Amis and Donald Davie. He was 25 when his first book, "Fighting Terms," was published.

Instead of staying on in England and reaping the rewards of early acclaim, Mr. Gunn moved to California soon after "Fighting Terms" was published in order to be with Kitay, an American he had met at Cambridge. For decades, Kitay remained frequent inspiration for Mr. Gunn's work, such as the love poems "Thoughts on Unpacking," "The Separation," "Touch" and "Hug." In a later poem, "In Trust," Mr. Gunn reflected on the couple's abiding bond, lasting through frequent separations:

As you began

You'll end the year with me.

We'll hug each other while we can.

Work or stray while we must.

Nothing is, or will ever be,

Mine, I suppose. No one can hold a heart,

But what we hold in trust

We do hold, even apart.

"He wrote often about San Francisco," said Lesser, "about homeless people he had seen on the street, or the beauty of landscape, or what it felt like to be a taxi driver in the city, even though he himself didn't know how to drive."

Mr. Gunn also wrote about his unconventional communal household: For years he and Kitay shared their home with close friends Bill Schuessler and Bob Bair. Another member of the acquired family, Jim Lay, died of AIDS in 1986. Mr. Gunn was HIV-negative.

"He loved his household and the fact that we ate together," Kitay said. "People were always astonished that we each had our own cooking nights."

"He had a terrific sense of humor," said Levine, whose association with Mr. Gunn dates back to Stanford University in the '60s. "He was a very pleasant guy to be with. Very physical, demonstrative."

"He was a lovely person, always interesting and fun," Lesser said. "A great gossip, but a bit taken aback by his own ability to make nasty comments, so that he was always modifying them with kinder remarks. He had an excellent memory and could remember, for instance, the names of the characters in the books his mother read him when he was a child.

"I will remember him as a dear friend who shaped my life in literature," she said, "and who made me understand how decent and satisfying and un- careerist the writing life could be."

Mr. Gunn is survived by Kitay; his brother, Ander, a photographer; an aunt, Catherine, who helped raise him after his mother's death; a niece, Charlotte; a nephew, Will; a grandniece, Emma; and a grandnephew, Joe.

Thom Gunn

(Filed: 29/04/2004)

Thom Gunn, who died on Sunday aged 74, wrote some of the best and most elegant poetry of his times; his early work shows the influence of Donne and Herbert, and he never lost their tightness of thought and structure, although from the 1960s he also came under the influence of mescaline, lysergic acid and Allen Ginsberg.

He found balanced metres and delicate rhyme schemes to produce poems about motorcyclists, truckers, a "cottaging" incident in a branch of McDonald's, drug-taking and Elvis Presley. A description of a heaving, orgiastic San Francisco "bathhouse" recalls Dante's Inferno not only in its content but also its terza rima.

The poem appeared in Boss Cupid (2000), a volume that caused less controversy for this than for Troubadour, a sequence of madrigal-like songs written from the perspective of Jeffrey Dahmer, the serial murderer, cannibal and necrophile.

"My weakness is that I like shocking people," Gunn remarked of that sequence. The collection appeared when Gunn was 70 and ripening into a vieillard terrible; it is his most accomplished book. "I've always counted on having a modern life span," he said. "I counted on learning things as I went along."

Not only was his technique always improving; as he grew older he also felt more able to write about what mattered most to him. As a tenured academic in America he was nervous of confessing his homosexuality, and he envied the confidence and freedom with which his friend Robert Duncan could write about it. He would refer to it teasingly or with innuendo until the 1970s.

What unites the wide range of themes Gunn approached, in an equally wide range of forms, is a rigorous mental process that examines states of mind and the words the poet finds to describe them. He was precise about moods, and a relentless inquirer into linguistic paradoxes. The Annihilation of Nothing is a characteristically philosophical exercise, and elsewhere he came up with phrases he could run backwards or forwards until they cancelled themselves out.

One poem begins, Indifferent to the indifference that conceived her; and another ends, The sentence is, condemned to be condemned. In spite of this careful, sometimes stiff method of composition, Gunn also had a novelistic, even gossipy way of looking at situations, from an early poem such as the unlikely First Meeting with a Possible Mother-in-Law to the bar-room banter of pieces written 40 years later.

Thomson William Gunn was born at Gravesend, Kent, on August 29 1929, the son of Herbert Smith Gunn, a journalist who was later to edit the Evening Standard, and Ann Thomson, who encouraged Gunn's early love of books.

When he was eight, the family moved to Hampstead. The heath left Gunn with a striking clash of associations: where I had played hide and seek / with neighbour children, played as an adult / with troops of men.

He was educated at University College School, Hampstead, except for a spell as an evacuee at Bedales in Hampshire.

Gunn's parents divorced when he was 11, the year he wrote his first poem, and also, to please his mother, a brief novel. Four years later she blocked a door with a filing cabinet and gassed herself. She was found dead by Gunn and his younger brother, Ander. It was 48 years before he produced a poem about it. Shocking as it is, The Gas-poker is exemplary of his calm and considered style.

After two years of National Service and six months in Paris, Gunn went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, from which he graduated in 1953. There he read English and set himself the task of writing a poem a week, which his friend Karl Miller would scrutinise.

He met F R Leavis only once, but admired him and recalled learning a lot from the Leavisites around him. At Cambridge he was a friend of the cartoonist Mark Boxer, and met an American student, Mike Kitay. When Kitay was summoned to Texas to serve in the US Air Force, Gunn sought a way of following him, and as a result ended up as a creative writing fellow at Stanford.

In 1954 Gunn's first collection appeared. Fighting Terms won immediate praise, particularly for the poem The Wound, which drew upon the Iliad and demonstrated a muscularity and rigour in its metre which was out of temper with the times. Compared with later work, the poetry seems restrained, but it still showed an early instinct for provocation - I was myself: subject to no man's breath: / My own commander was my enemy.

The book has the formality of Marvell, but an updated attitude towards sexual politics. This was the age of "The Movement", a loosely-bracketed bunch of poets centred around Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis. "To my surprise," Gunn said later, "I also learned that I was a member of it."

At about this time, Gunn, then 25, met Christopher Isherwood, who was 50 at the time and took the young poet under his wing.

Gunn enjoyed the gossip he winkled out of the novelist, whom he tried to impress with his own youthful cattiness. Later, though, he would come to regret this "pertness, amounting to rudeness", particularly about Cecil Beaton, with whom he would come to develop a firm friendship.

A second volume, The Sense of Movement, was published in 1957. Here, the poet summed up the spirit of his age, calling it generation of the very chance / It wars on, in a hymn of praise to Elvis Presley, who turns revolt into a style, prolongs / The impulse to a habit of the time. Elsewhere, he captured the restlessness of biker culture in the memorable pentameter, One is always nearer by not keeping still.

In 1958 he joined the staff of the University of California, Berkeley, and set up home with Mike Kitay in San Francisco. The couple lived together there for the rest of his life, in spite of Gunn's ceaseless clubbing and cruising. He was still less faithful to his teaching duties, which he dropped in 1966, later confessing: "I said I wanted to devote myself to poetry, but the real reason was that I wanted to go to concerts in the park and take acid." In 1975, he took a post as Visiting Lecturer at Berkeley.

It was the scholar Tony Tanner who passed Gunn his first joint, and in Moly (1971) Gunn enthusiastically recorded some subsequent hazes. The matter is pure Sixties, but again, the music is Marvell's: My methedrine, my double-sun, / Will give you two lives in your one, / Five days of power before you crash.

Two poems are suffixed by a note that the poet was on acid while composing them. Where his imagery had been complex before, now that he was off his head it seemed clearer, if only because of the reader's impression that Gunn was hallucinating.

With the publication of Jack Straw's Castle in 1976, Gunn managed to address homosexuality in a relaxed, Whitmanesque voice. By now his metre was relaxing too, and he experimented with free verse. This proved more controversial than anything Gunn had to say about sex and drugs; English critics in particular were sniffy about the change in form.

Just when Gunn had begun taking pleasure in exploring his way of life in verse, it was transformed. In the 1980s many of his friends contracted the Aids virus. He admitted he had shared needles with other drug users and had freely enjoyed adventurous forms of sex, but he did not catch the disease.

The Man with Night Sweats (1992) contains laments for his lost friends, and sounds a bemused note of survivor guilt: the poet is missed / From membership as if the club were full. / It is not that I am not eligible. The book won the first Forward prize. The collection also included poems about ornithology, skateboarding and marine life (the last written with children in mind).

In 1999 Gunn retired from teaching. He was by then Senior Lecturer at Berkeley, and had a distinguished record as an academic, producing editions of Fulke Greville in 1968 and in 1974. From 1958 to 1964, he covered poetry for the Yale Review. He was a generous and broad-minded critic, standing up for Ginsberg, and was scrupulous in his judgment.

As he explained in an epigram, You scratch my back, I like your taste it's true, / But, Mister, I won't do the same for you, / Though you have asked me twice. I have taste too.

He remained a perfectionist in poetry, and stoutly defended the English language against abuse: "You'd be surprised at what the dictionaries say nowadays. Following new usage, they say 'lack of interest' is one of the word [disinterested]'s meanings. Good Lord! I'll be dead soon. I don't need to live in this new world."

Thom Gunn is survived by Mike Kitay, and a cat, Rose.

|

|

|

|

Obituary

Thom Gunn

May 6th 2004

From The Economist print edition

Thomson William Gunn, poet and rebel, died on April 25th, aged 74

SOMETIME in the late 1950s, in northern California, Thom Gunn came across a

roaring company of bikers in their leather gear. The sight was not unusual in

those days, but it was strange for that particular place, in open fields that

had been haunted until then only by blue jays and swallows. Mr Gunn began to

muse on the natural instinct of the birds and the crowd-compulsion of the

bikers, both flocking noisily, and wrote what was to become his best-known poem,

“On the Move”:

Much that is natural, to the will must yield.

Men manufacture both machine and soul

And use what they imperfectly control

To dare a future from the taken routes.

For some readers, however, these verses were less about instinct and will than about the thrill of leather, steel and muscle. By moving from England to America in 1954 to live with his male lover and to explore the California bath-house culture, Mr Gunn had acknowledged himself a homosexual, and he was to become perhaps the best gay poet writing in English. But it was many years before he dared to come out in his poetry. Had he done so, in the 1950s, he would never have got his teaching job at Berkeley.

Not merely the need for a job restrained him, but the forms and traditions of poetry itself. Mr Gunn, a fine and deliberate wordsmith, revered the rhythms of Spenser, Milton and Dante all through his writing career. Accordingly he also clung to the themes beloved by older poets, including heterosexual love. His first book of verse, “Fighting Terms”, published just after his graduation from Cambridge in 1953, opened with a battle poem based on Homer's “Iliad”. It then moved on, via homage to Donne (“To his Cynical Mistress”) to coy games between men and women:

Even in bed I pose: desire may grow

More circumstantial and less circumspect

Each night, but an acute girl would suspect

That my self is not like my body, bare.

The book also contained a poem to his lover, Mike Kitay. It was carefully disguised not only in Elizabethan stanzas but in an Elizabethan metaphor, of tamer and hawk:

Even in flight above

I am no longer free:

You seeled me with your love,

I am blind to other birds—

The habit of your words

Has hooded me.

Mr Gunn's self was not laid bare for a long time. He left England hoping, in his words, to be someone new. The English always wanted to categorise him, lumping him with Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin as a “Movement” poet (though he had never met Larkin), and anthologising him with Ted Hughes because he was young and angry, though he had nothing of Mr Hughes's primal violence. In fact, he was more often lyrical and tender: instead of scraggy crows, soft-footed cats.

America, however, quickly became a succession of masks and intense experimentation. In 1966 he gave up teaching, telling colleagues that he wished to devote himself to poetry. On the contrary he wanted to take drugs, pick up lovers and listen to rock concerts in the park. In his verse, he took on the voices of drop-outs and speed-sellers. Formal metre (“filtering the infinite through the grid of the finite”, as he once put it) remained a cover for him; even on LSD, he could still scan.

Landscape of acid:

Where on fern and mound

The lights fragmented by the roofing bough

Throbbed outward, joining over broken ground

To one long dazzling burst; as even now

Horn closes over horn into one sound.

As he grew older he relaxed, as poets tend to. He wrote a little more about his past: a childhood on the North Kent coast, lingering in the marshy graveyard of Dickens's “Great Expectations”, and a bookish Hampstead boyhood, lying on Parliament Hill with Lamartine's poems. In 2000 he managed at last to commemorate his mother's suicide, which he had stumbled on at 15, by using the third person and “withdrawing” the first.

He also relaxed into his homosexuality, now serenely domesticated, and into free verse, shocking his readers far more with that. “Jack Straw's Castle” (1976), a collection named after a gay cruising spot on Hampstead Heath, seemed to be a celebration of exuberantly broken rules. But times changed. As the AIDS epidemic began to kill his San Francisco friends in the 1980s, Mr Gunn turned back instinctively to formal metre to mourn them, as in “The Man with Night Sweats”:

I wake up cold, I who

Prospered through dreams of heat

Wake to their residue,

Sweat, and a clinging sheet.

As his friends died around him, Mr Gunn often questioned why he had been spared. Their deaths, he wrote, “have left me less defined/It was their pulsing presence made me clear.” Nor could he feel anything but emptiness beyond them. “On the Move” had ended with lines reminiscent of T.S. Eliot:

At worst, one is in motion; and at best,

Reaching no absolute, in which to rest,

One is always nearer by not keeping still.

“I'm not sure that the last line means anything,” he told an interviewer in 1999. “Nearer to what?”

Poet's Choice, by Edward Hirsch

By Edward

Hirsch

Sunday, May 23, 2004; Page BW12

Thom Gunn, who died in April at the age of 74, was a lively Anglo-American poet with a warm heart and a cool head, a rare combination. His rigorous intelligence and sympathetic imagination are everywhere in evidence in his 12 books of poems.

Poetry on both sides of the Atlantic has been enriched by his Collected Poems, which brings together nearly four decades of work from his assured first book, Fighting Terms (1954), to his sunlit middle collection, Moly (1971), to his magisterial book of elegies, The Man With Night Sweats (1992). His final collection, Boss Cupid (2000), suggests that this excellent verse technician was, in the end, a provocative gay love poet.

Gunn was a transplanted British writer who identified strongly with San Francisco, his adopted home town. He studied with the poetic rationalist Yvor Winters at Stanford (the Library of America recently published his excellent edition of Winters's Selected Poems), who ingrained in him a permanent sense of the rigor and balance of the Elizabethan plain style. As he wrote in a tribute poem to Winters:

You keep both Rule and Energy in view,

Much power in each, most in the balanced two:

Ferocity existing in the fence

Built by an exercised intelligence.

What he concluded about his former teacher is also eminently true of himself: "For all his respect for the rules of poetry, it is not the Augustan decorum he came to admire but the Elizabethan, the energy of Nashe, Greville, Gascoigne, and Donne, plain speakers of little politeness."

Gunn was very much at home in the traditional meters of English poetry, though he also liked to experiment with syllabic stanzas and looser free verse rhythms, with what he called "openness." He had "little politeness," and part of the shock of his work is the way he employed a plain style and traditional English meters to write about the contemporary urban life he found in California -- about drugs and panhandlers, gay bars and tattoo parlors. There is a powerful dialectic -- a high tension -- running throughout his work between raw anarchistic energy and powerful intellectual control. His poems enact an ongoing struggle to keep Rule and Energy in right relation, proper balance.

Gunn insisted on the continuity between England and America, between meter and free verse, between epiphanic vision and everyday consciousness. His existential rebelliousness was tempered by a sense of our common humanity. I would say that his Elizabethan manner reached its peak in his sequence of elegies for friends who died during the AIDS epidemic of the late 1980s. Here is a memorial lyric for his friend Larry Hoyt, whose life was too early stilled:

I shall not soon forget

The greyish-yellow skin

To which the face had set:

Lids tight: nothing of his,

No tremor from within,

Played on the surfaces.

He still found breath, and yet

It was an obscure knack.

I shall not soon forget

The angle of his head,

Arrested and reared back

On the crisp field of bed,

Back from what he could neither

Accept, as one opposed,

Nor, as a life-long breather,

Consentingly let go,

The tube his mouth enclosed

In an astonished O.

(Quotations are from Thom Gunn, "Collected Poems." Farrar Straus Giroux. Copyright © 1994 by Thom Gunn.)

Moving voice

Thom Gunn's parents divorced and

his mother committed suicide, but at Cambridge his poetry found admirers. He

followed a boyfriend to San Francisco where he experimented with free verse and

drugs, and documented the tragedy of Aids. Some critics rejected this new

direction, but at 73 his status seems assured

Robert Potts

Saturday September 27, 2003

The Guardian

Read this article, here

A Poet's life

Reserved but

raw, modest but gaudy, Thom Gunn covered an enormous amount of ground in his

exquisite work and his raucous life

Monday, April 25, 2005

Thom Gunn, the British-born San Francisco poet who died a year ago this week, is remembered by friends, colleagues and intimates who recall the polarities, the ghosts, the charms, the legacy of the man

Read this article, here

April 29, 2004

Fine Old Thom

The poet Thom Gunn was well-established in the English department at U.C. Berkeley when I passed through it in the late 70's, but I never met or studied under or otherwise encountered him. In fact, it was not until the last 7 or 8 years that I started reading his poetry in any quantity. I pulled down my copy of his Collected Poems on Sunday evening, to add it to the reading/rereading stack by the bed, and learned only yesterday, as I was catching up again with a number of poetry weblogs, that he had died on Sunday at age 72. There are any number of citations, quotations and appreciations of his work accumulating online on the occasion of his passing -- e.g., these from Mike Snider and Jonathan Mayhew.

Some poets -- Dryden springs to mind -- emerge as primary eyewitnesses to their period. It was Thom Gunn's fate, surely unlooked for, to become one of the foremost chroniclers of the AIDS pandemic as it had its way with countless friends and acquaintances in the San Francisco gay community. The poems from that time -- most notably in his 1992 collection The Man With Night Sweats (also included in the "Collected") -- tie in to the centuries-long line of English elegists.

Gunn studied with Yvor Winters at Stanford in the late 1950s, and the two seem to have approved of one another. Gunn recently edited the new American Poets Project volume of Winters' Selected Poems, and included a poem "To Yvor Winters, 1955" -- there are Airedales in it -- in his 1957 collection, The Sense of Movement. More details on the Winters connection come from the Guardian's obituary:

It was primarily to be with Mike Kitay, his lifelong partner, that Gunn applied for a creative writing fellowship at Stanford University, California, which he was awarded in 1954 and where he worked with the great if wayward poet-critic Yvor Winters.

The juxtaposition of Gunn's metaphysical Englishness with Californian life and Winters' reaching is very evident in his second collection, The Sense Of Movement (1957), an exciting, deliberately provocative book whose distinctive energy comes from an apparent tension between form and content: traditional poetic structures and intellectual abstraction are deployed on subjects which include Hell's Angels, Elvis Presley, and a keyhole-voyeur in an hotel corridor.

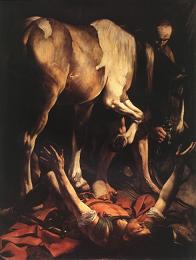

Winters included his student compatriot Gunn in the relatively short list of contemporary poets whose work he found tolerable in his excellent study of the short poem in English, Forms of Discovery, and in the companion anthology Quest for Reality he reprinted this poem, which opens Gunn's 1961 collection My Sad Captains and is illustrated here with the painting to which it refers:

|

In Santa Maria del Popolo

Waiting for when

the sun an hour or less |

Click to enlarge |

But evening

gives the act, beneath the horse

And one indifferent groom, I see him sprawl,

Foreshortened from the head, with hidden face,

Where he has fallen, Saul becoming Paul.

O wily painter, limiting the scene

From a cacophony of dusty forms

To the one convulsion, what is it you mean

In that wide gesture of the lifting arms?

No Ananias

croons a mystery yet,

Casting the pain out under name of sin.

The painter saw what was, an alternate

Candour and secrecy inside the skin.

He painted, elsewhere, that firm insolent

Young whore in Venus’ clothes, those pudgy cheats,

Those sharpers; and was strangled, as things went,

For money, by one such picked off the streets.

I turn, hardly

enlightened, from the chapel

To the dim interior of the church instead,

In which there kneel already several people,

Mostly old women: each head closeted

In tiny fists holds comfort as it can.

Their poor arms are too tired for more than this

-- For the large gesture of solitary man,

Resisting, by embracing, nothingness.

Posted by George Wallace here

|

Now as I watch the progress of the plague,

I do not like the statue’s chill contour,

Contact of friend led to another friend

I do not just feel ease, though comfortable:

But death—Their deaths have left me less defined:

Eyes glaring from raw marble, in a pose —Abandoned incomplete, shape of a shape,

In which exact detail shows the more strange,

|

OS QUE DESAPARECERAM

Ao observar hoje o progresso da peste, Os amigos que me cercam adoecem, definham, Vão-se embora. Nua, será menos vaga a minha forma, Nitidamente exposta e de pele esculpida?

Não me agrada o contorno frio da estátua, Não, nos tempos que correm. O calor que me investia Levava para fora por meio da mente, membro, sentimento e mais, Numa envolvente família que crescia.

Contacto de amigo levava a outro amigo, Subtil entrelaçado através da massa viva, Que, tanto quanto sabia, podia não ter fim, Imagem de um abraço ilimitado.

Não era só sentir-me à vontade e confortável: Agressivos, como num qualquer ideal de desporto, Em contínuos movimentos vibrando pelo todo, O ímpeto deles mantinha-me tão firme como o seu apoio.

Mas a morte – a morte deles deixou-me menos definido: Era a sua palpitante presença que me tornava claro. Apropriava-me dela, não tinha fronteiras, eu, Que esta noite aqui oscilo sem apoio.

Do mármore cru olhos fitam, numa pose Lânguida, em parte soterrada no bloco, Perfeitas as canelas e sem coxas, como que paralisado Entre o virtual e a obra acabada.

- Abandonado incompleto, forme de uma forma, Em que o pormenor exacto ainda a faz mais estranha, Preso da incompletude, não acho fuga No regresso ao constante jogo do dar e permutar.

Tradução de João Ferreira Duarte, em "LEITURAS poemas do inglês", Relógio de Água, 1993. ISBN 972-708-204-1 |

|

The Man with Night Sweats I wake up cold, I whoProspered through dreams of heat Wake to their residue, Sweat, and a clinging sheet. My flesh was its own shield: Where it was gashed, it healed. I grew as I explored The body I could trust Even while I adored The risk that made robust, A world of wonders in Each challenge to the skin. I cannot but be sorry The given shield was cracked, My mind reduced to hurry, My flesh reduced and wrecked. I have to change the bed, But catch myself instead Stopped upright where I am Hugging my body to me As if to shield it from The pains that will go through me, As if hands were enough To hold an avalanche off. |

|

THE BUTCHER'S SON

Mr Pierce the butcher |

|

You are already |

Painting by Vuillard

Two dumpy

women with buns were drinking coffee |

It was your birthday, we had drunk and dined

Half of the night with our old friend

Who'd showed us in the end

To a bed I reached in one drunk stride.

Already I lay snug,

And drowsy with the wine dozed on one side.

I dozed, I slept. My sleep broke on a hug,

Suddenly, from behind,

In which the full lengths of our bodies pressed:

Your instep to my heel,

My shoulder-blades against your chest.

It was not sex, but I could feel

The whole strength of your body set,

Or braced, to mine,

And locking me to you

As if we were still twenty-two

When our grand passion had not yet

Become familial.

My quick sleep had deleted all

Of intervening time and place.

I only knew

The stay of your secure firm dry embrace.

|

|

Tamer and Hawk

I thought I

was so tough,

|

|

Days are

bright,

Look at me

Shiny board

I crouch

close

Legs go

loose,

Like a

scales.

So it ends |

|

Jesus and His Mother

My only son, more God's than mine, Stay in this garden ripe with pears. The yielding of their substance wears A modest and contented shine: And when they weep in age, not brine But lazy syrup are their tears. "I am my own and not my own."

He seemed much like another man, That silent foreigner who trod Outside my door with lily rod: How could I know what I began Meeting the eyes more furious than The eyes of Joseph, those of God? I was my own and not my own.

And who are these twelve labouring men? I do not understand your words: I taught you speech, we named the birds, You marked their big migrations then Like any child. So turn again To silence from the place of crowds. "I am my own and not my own."

Why are you sullen when I speak? Here are your tools, the saw and knife And hammer on your bench. Your life Is measured here in week and week Planed as the furniture you make, And I will teach you like a wife To be my own and all my own.

Who like an arrogant wind blown Where he pleases, does without content? Yet I remember how you went To speak with scholars in furred gown. I hear an outcry in the town; Who carries this dark instrument? "One all his own and not his own."

Treading the green and nimble sward, I stare at a strange shadow thrown. Are you the boy I bore alone, No doctor near to cut the cord? I cannot reach to call you Lord, Answer me as my only son. "I am my own and not my own."

1954 |

POEM OF THE WEEK

MAY 30 2017

Thom Gunn (1929–2004) served two years’ National Service in the British Army before attending the University of Cambridge, and he published his first book of poetry, Fighting Terms (1954) the year after he graduated. Though his early formal work was widely praised in England, Gunn soon emigrated with his partner, Mike Kitay, to California, where he would live for the rest of his life. In writing about his numerous collections of poems, including My Sad Captains (1961), Jack Straw’s Castle (1976) and The Passages of Joy (1983), critics have often pointed to Gunn’s fusion of disparate languages, employing traditional poetic forms to describe elements of popular culture. When the AIDS pandemic swept through the United States in the 1980s and 90s, claiming the lives of many of his friends and loved ones, Gunn gave voice to the profound loss felt by an entire community with his collection, The Man with Night Sweats (1992).

“Buchanan Castle, 1948”, published in the TLS in 2008, was never included in any of Gunn’s collections during his lifetime. Perhaps this account of a speaker struggling to come to terms with his sexuality in the male-dominated culture of the military (“the hierarchy based on fear”) felt too raw and confessional for Gunn to share again. Present in this young man is the hunger of a poet to “capture” and “penetrate” to “the core within the core” of things. Consigned to a menial task at which he fails (“I do not even sweep the dust up well”), the speaker nonetheless aims to “take charge” of his life through self-expression; writing poems with “marching lines” of “taut perfection” might help him find his own true voice, “and give it out to every passerby”.

Buchanan Castle, 1948

Detailed today to clean the barrack room,

I line the black iron bedsteads up the middle.

I sweep one side then stray, trailing the broom,

To the window where I see the distant men,

My own platoon, at drill. Testing again

A natural law as if it were a riddle,

I watch the order mouthed, the stamp of feet

I cannot hear till after a delay

– As if their sounds were held back by the heat.

All summer in this Victorian castle I seem

To lag behind my own steps in daydream.

I dream an incantation through the day:

If I could find the core within the core,

Could penetrate the shell within the shell,

Then only could I reach the crusted ore

And give it out to every passer-by.

Phrasing such abstract generosity

I do not even sweep the dust up well.

If I could find the language for what is:

The castle, the hierarchy based on fear,

The constant practice for the ceremonies,

The taut perfection of the marching line,

Brass cleaned to sunshine, pleats, the bagpipe’s whine;

And if the language caught the motion here,

By the act of capture I would be released

Into my freedom, into the world at large

– World of routine and rainstorm – where

at least

I could, while lingering in the small bright lane

Picking through black slugs brought out by the rain,

Hear hope, the crack my cleats make, and take charge.

THOM GUNN (2008)