12-6-2002

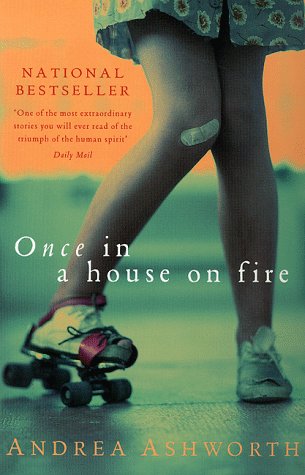

ONCE IN A

HOUSE ON FIRE

by

Andrea Ashworth (b. 1969)

| |

Li este livro há cerca de dois anos e impressionou-me muito.

Trata da violência doméstica, um assunto grave mas que muitas vezes é tabu

na nossa sociedade. Está já traduzido nas principais línguas europeias, mas

ainda não apareceu em português.

DE -

Als

unser Haus in Flammen stand -

Taschenbuch, Heyne

Aus dem Engl.

von Angelika Naujokat

FR - La petite fille de

Manchester -

Ramsay

trad. de l'anglais par Simone Manceau

IT -

Una

volta, in una casa in fiamme - Feltrinelli

Traduzione di Simona Riminucci

SP -

Erase una vez una casa en llamas

- Espasa

NL - Eens in een brandend huis

- Anthos

SE - En gång i ett hus som

brinner -

Samhälle

NO - Ut av det brennende huset

- Gyldendal

DK - Engang, i et hjem i flammer

- Vinten

PL

- Pożar w moim domu - Zysk i

S-ka

|

|

|

|

July 12, 1998

By CAROL WEST

My father

drowned when I was 5 years old,'' Andrea Ashworth writes of her early years with

her sister Laurie. ''By the time I was 6, our mother's stomach was swollen full

of a third child. . . . A looming, red-faced man, quite a bit older than her,

stepped into our house for tea and was introduced to Laurie and me as our new

daddy.'' So begins ''Once in a House on Fire,'' Ashworth's mesmerizing and

poetic memoir of violence, abuse, racism and poverty that chronicles her

harrowing journey from Manchester to Oxford. Ashworth, who was born in 1969,

writes that her new stepfather turned out to be a drunk who beat her up and

molested her. Strangers on the street called the girls ''wogs'' and ''dirty

Pakis'' -- they had inherited the dark skin of their Maltese father. Their

mother was married again, this time to a man who abused all of them to the point

that the mother wound up in a hospital. Through the eyes of an anguished child,

Ashworth vividly depicts the abuse, physical and sexual; a disastrous move to

Canada; a life of poverty; and repeated rescue attempts by loyal friends. She

was sustained by literature; she saved ''serious swoons for James Joyce, Graham

Greene and Thomas Stearns Eliot,'' and writes that her mind soared ''over

sonnets and odes that make miserable things seem sublime.'' Encouraged by her

teachers, Ashworth was accepted at Oxford. Her sister Laurie escaped to a girls'

hostel, and her youngest sister, Sarah, who had taken to burning and cutting

herself because ''it hurts less,'' was considered for placement in a foster

home. Their mother, hopelessly self-destructive to the end, ''clutched my hair

and branded my forehead with a vicious, burning kiss'' and told Ashworth, ''You're

my hope.'' That hope has been fulfilled in this book.

B B C

Biography

Andrea Ashworth's memoir, Once in a House on Fire, recounts her story of

growing up in inner-city Manchester in the 1970s and '80s. The story follows

Andrea, her two sisters and her mother in their battle with poverty, domestic

violence and the effects of depression.

The

award-winning book has been adapted for the stage and is currently being made

into a feature film. It's often used to inspire study and discussion in schools

and universities.

As a

child Andrea sought ways to escape through books and imagination, solidarity

with her sisters and encouragement from teachers.

At

eighteen, she won a place to study at Oxford University, where she earned her

B.A., M.A. and D.Phil., and went on to become a lecturer then Junior Research

Fellow in English Literature.

Andrea has written several anthologized short stories, essays and introductions

to Penguin Classics, and her work has been featured in The Times, The Observer,

The Telegraph, TheIndependent, The Daily Mail, The Guardian, The Times Literary

Supplement, Elle and Vogue.

She

works with several British charities focused on protecting children and adults

from poverty and violence and is an advocate for literacy and education for

those in need.

Recently awarded the Hodder Fellowship in Creative Writing at Princeton

University, USA, she is now completing her first novel.

Hitting Home - Domestic

violence

Why did you write 'Once in a

House on Fire'?

I felt a desperate thirst to

read a book that might tell me something about my life, which felt so

topsy-turvy. I was looking for a story that might help me to see more clearly,

to understand what had happened, help me feel less alone and freakish because of

my background. In the end, because I couldn't find the book I was looking for, I

resolved to write Once in a House on Fire.

After I graduated from Oxford, my life seemed to be bursting with promise. I won

a scholarship to Yale, in America, and it was then, when things were going so

fantastically well, that I suffered a kind of seasickness. It was hard to

reconcile where I seemed to be going to with where I was coming from.

I had always wanted to write

stories and poems but I realized that if I didn't pin down the ghosts of my past,

those blue-black butterflies would go skittering across anything else I tried to

write. And I had to capture that spooky stuff, give it a good home on paper, in

order to keep it from overshadowing my life.

What was it like revisiting

all those childhood memories?

Memories would surge,

vivid-beautiful and horrible-while I was writing

Once in a House on Fire. There were

times when I felt freshly terrified. It was painfully confusing to relive my

childhood-flashes of knives against my mother's face; never enough money for

milk and bread; my stepfather's fists clenching with an angry life of their

own-while my grownup life was unfurling among the spires of Oxford. Sometimes I

felt lost, thrown back to being a frightened nine-year-old, helpless. But I knew

that looking back was the only way for me to move-truly, freely-forward.

When readers began to respond

with such generous warmth to Once in a

House on Fire, I discovered a new freedom from all the old fears of

my childhood. It was a fantastic relief to feel heard, understood, to finally

share the story. I feel lucky, and very grateful.

What would you say to children

who are in a similar situation?

There are too many children

still trapped in dark situations. Please remember: you're not alone. It's

natural to be afraid, but you mustn't feel ashamed. Take responsibility for your

own well-being and happiness, not for the unhappiness and confusion and anger of

everyone around you. What's happening is wrong. You don't deserve it, and you

can live differently for yourself.

Try to talk to a teacher or some other trusted adult about what's troubling you.

Or call ChildLine 0800 1111. And don't forget that-whatever your

beginnings, whatever fears you might carry with you as you grow, however hard it

may all seem-you can build your own world. You can make a good, bright life.

You'll be free to be-and enjoy being-who you choose to be.

Why do you think it's so hard

for people to tell anyone they're suffering domestic abuse?

I wish I had felt less ashamed

and afraid of telling someone, perhaps a trusted teacher or a friend's parent,

about what was happening to me at home. Even if things had remained as violent

and frightening as ever, I think my sisters and I would have felt less cut off

from the world and more hopeful about the future. Now there's much more openness

about what goes on in troubled homes, though there is still too much secrecy and

shame and suffering. Perhaps if we'd felt able, back then, to speak up, our

lives would have become safer and brighter a lot sooner.

How does your mum feel about

what happened?

My mum of course wishes from

the bottom of her soul that none of the monstrous stuff had ever happened. She

aches to be able to erase the past, to go back, now she's stronger, and make

things different.

If there had been less shame

and secrecy surrounding domestic abuse when we were little, perhaps she'd have

felt more confident and supported in her efforts to pull away from her violent

relationships. Perhaps she'd have been less inclined to blame herself for the

explosions and misery, more ready to ask for help. Perhaps escape wouldn't have

seemed so flatly, darkly impossible.

Physically and psychologically

beaten women often feel they deserve their abuse. They become caught in a web of

guilt, exhaustion, extreme fear, hopelessness and-the stickiest of all the web's

strands-love. These combined pressures, not to mention overwhelming practical

anxieities about food and money and housing, can keep people clinging to

relationships that damage and even threaten to kill them and their children.

What would you say to women in

the same situation as your mum?

To anyone caught like this, my mother and I together say:

we wish you the courage to find safety and happiness. Don't underestimate your

own strengths and don't be afraid to ask for help. Escape may seem impossible,

but it's not. You don't have to live like this.

You can change your life.

What influence do you think

the violence had on your mum's relationship with you and your sisters?

The violence made my sisters

and me closer to our mother in some ways, passionately protective of her and one

another, and extremely appreciative of gentleness. But it also inflicted

long-lasting, invisible bruises, much worse than the obvious, physical ones that

looked so nasty but healed naturally: bruises of deep fear in my sisters and me,

and of guilt, as well as fear, in my mother. Hard things to outgrow: moving on

from that sort of damage involves the shedding of many skins. It takes a lot of

time and energy and loving communication.

While she was a victim, however, my mother was also, always, adamant that my

sisters and I should never have to suffer as she did once we had grown up. She

was determined that our futures would be safer and brighter and happier, as they

have turned out to be.

As a child you should amazing

resilience, how has your experience affected your adult life?

The darker aspects of my

childhood have probably made me shy of petty tensions and the big power games

that can often colour romantic relationships and other friendships. I gravitate

towards very honest relationships, based on mutual trust and respect and

affection, quite free of conflict. My love is inspired by a desire to be close

to someone, rather than fear of being alone.

In some sense, my background did me a great favour in showing me, very

dramatically and often in terrifying ways, how I don't want to live and relate

to other people. There was at the same time an abundance of love in my childhood,

from my mother and aunties and especially my sisters. This sustained me through

many chaotic years and is still the centre of my life.

How do you feel now about your

stepfathers. Do you have any contact with them?

Towards my first stepfather,

who was cold and cruel in all sorts of ways, I don't think I harbour any

feelings at all. No anger, no pity, no love. But my second stepfather could be

loving and vivacious at times, as well as monstrous and out of control at others,

and I recently discovered, through a little, brief contact with him, that I

still feel vestiges of daughterly affection for him. (But no fear, finally.) I

wish he'd had a less traumatized childhood and a better education, so that he

might have felt better about himself, which might have made him much less

desperate and viciously angry at the world.

What are your feelings about

perpetrator programmes

I salute any programme that

encourages men and women to feel better about themselves and to behave with more

respect and kindness towards one another. I also believe that, while it makes

sense to focus energy and attention upon the victims of violence, who are often

women and children, we aren't going to stop the cycle of explosions without

addressing the roots of the trouble too.

We need to ask not only: why

do some people tolerate violence against themselves and their children? But also,

getting to the heart of the matter: why do some people feel compelled to

perpetrate violence? And how can we help them to free themselves of these

feelings, and thereby make their victims, their loved ones, free from damage and

fear?

What are you all doing now

since we left you in the book?

I'm delighted to say that my

mother and sisters and I are very happy and well nowadays. The differences

between our past and our present make me dizzy; I often have to pinch myself in

the face of my good fortune.

I enjoy a very rewarding life

(with a lovely and gentle man), teaching and writing. And I like to be involved,

where I usefully can, with projects dedicated to helping children and young

people in distress to improve their lives. I find it deeply rewarding to think

that what happened to my family might end up making some good difference in

other people's lives.

My mother has moved to Devon,

where she looks after mentally disabled people and enjoys a peaceful and busy

life that involves friends and laughter and venturing in a kayak on the sea! She

still works too hard, but she is safe, optimistic and finally proud of herself.

My sister Lindsey lives a

sweet life with her fiancé in Paris. She does translations and is a ballet

dancer and an accomplished mountain climber.

My youngest

sister Sarah, who lives in London, is a truly amazing, bright and lovely person.

She pulled herself out of a terrifying childhood and has pushed through

fantastic transformations to become first a full-time cardiac technician and now

a university lecturer in the subject. At the same time, she is single-handedly

raising a gorgeous little girl, my niece Hannah, whose happiness makes all our

lives brighter.

Once in a House on Fire by

Andrea Ashworth, read by the author

(Macmillan £8.99, running

time 3hrs)

Kim

Bunce

Sunday October 7, 2001

The Observer

When Andrea Ashworth was five years old, her father, a

painter and decorator, died in a freak accident. Her sister, Laurie, was three,

her mother, Lorraine, 25. The three of them made a dark-haired, tragic trio,

secure in their terraced house paid for with the life insurance money. But the

real tragedy of Ashworth's childhood begins when stepfather number one moves

into their lives, later to be replaced by stepfather number two. Both men beat

Andrea's mother until her youth and beauty die behind black eyes and sleeping

tablets and years of marital rows that leave Andrea with a terror of home but a

talent for excelling in every other aspect of her life: 'My fear of our house

made everything else a breeze.'

Listening to the thin-voiced

Ashworth recount the horrors of her childhood seems the most natural thing in

the world. She is neither arrogant about her achievements nor self-pitying in

describing the hours spent at her mother's bedside when she was too 'tired' to

get up and make the children's tea. Nor is she shouting out for sympathy when

the listener learns how she ironed her dirty school uniform to make it look

respectful. Her lavish use of adjectives bring a light to the dark landscape of

Manchester in the Seventies ('a stony row of brooding chimneys, next to the

giant industrial ones that rose up like kings and queens on a chessboard'), and

humour to an otherwise pitiful tale.

EMERGING WOMEN WRITERS

Once in a House on Fire

by Andrea Ashworth, Copyright 1998 by Picador--A Review by J.M. Barnett

It should come as

no surprise when a 29-year-old fellow at Oxford University writes her first

book. The surprise lies, in this case, in the subject matter. Once in a House

on Fire, only recently released for sale in the United States, is the memoir

of Andrea Ashworth, who grew up in a world of abject poverty and unceasing

household violence. Her father drowned in the 1970s when she was five and her

sister was just three. Soon afterwards their mother married a brute who

physically abused both wife and children.

The "family" moved

to Canada, where, in a beautiful setting, the new stepfather continued to

torment his victims. After selling the family jewelry, Andrea's mother took her

daughters back to industrial Manchester, where she tried to survive without a

husband. Eventually a second stepfather entered Andrea's life. When the brief,

friendly courtship ended, including a prison stint for burglary, he turned out

to be every bit as violent as the first stepfather. Throughout the turmoil, as

Andrea's mother vacillated between throwing out the bums and yielding to their

every whim, Andrea and her sister maintained their self-esteem, their empathy

and their determination to succeed in their studies. At twenty-eight, Andrea

Ashworth became one of the youngest fellows at Oxford University. She is now

working on her first novel.

Once in a

House on Fire, for all its horrific scenes and foul language, is actually a

story of triumph. Knowing that the story is true makes it more chilling, more

thrilling than a novel. Sensitive and observant children may often find refuge

in the world of science and literature. Not many of them, however, survive

brutal hell, serve as role models and share their experiences movingly as Andrea

Ashworth does in this, her first book. If you liked Anna Quindlen's Black and

Blue and/or Frank McCourt's

Angela's Ashes, be sure to

read Once in a House on Fire.

|

|

"Writing this was a real

sanity-saving exercise."

|

|

|

Andrea Ashworth is speaking about her book "Once in a House on Fire" which has

been praised by reviewers such as Carol West of the NY Times, who called it a "mesmerizing

and poetic memoir of violence, abuse, racism and poverty."

Dr.

Ashworth, born in England in 1969, is one of the youngest research Fellows at

Oxford University, where she earned her doctorate.

Her

choice of nonfiction as her first work was a matter of wanting to deal with her

past, and then be able to move on to writing fiction. She is currently working

on her first novel. "I wanted to get my memories out because I wanted to pin

them down, so that all those ghosts wouldn't go streaking across the novels,"

she explains.

"The

reason I called it a memoir, and shaped it that way, although it's in the form

of a novel, and I tried to write it in a very entertaining way, was because I

wanted to be fair to the reader. I think a writer has a contract with her

readers, and I thought it would be misleading and perhaps coy to call it

anything other than a true story," she says.

Ashworth notes she did not start writing this chronicle of her early life until

after she had left England. "It gave me the luxury of time and distance to look

back, and contemplate what had happened," she says. "I was hit by the

incongruity, by the weirdness, of where I was coming from, compared to where I

seem to be going."

She

recalls as a girl writing "lots of poems and stories and so on, which was very

much disproved of by my stepfather. He was always very threatened by literacy,

and also by expressions of warm feeling. Most of what I wrote was dedicated to

my mother."

She

found journal writing as a child was a kind of emotional buffer against the

abuse and difficult circumstances she experienced. "I wouldn't have known that's

what it was then, but I know I found it a very sweet pleasure. And I found

reading and writing a sanctuary."

Ashworth thinks the process of writing fiction, on the other hand, is "hugely

different. It's a massive challenge, and a luxury, to be free to make it all up.

The great thing is, I don't have to go back to all the dark and scary places

that I had to troll through in 'Once in a House on Fire.'

"But

of course, the hard thing is that in making it all up, I have to conjure its

reality for myself, and seduce myself into the fiction. I sometimes find myself

sort of resisting, saying, well, here is a character and she has ten fingers and

ten toes, and now let's walk her across the room. So that's been interesting. I

have a very funny relationship with this different kind of writing, because it

doesn't cause me any pain.

"My

apprenticeship in writing was a very painful one, so it seems strange, a little

bit like walking on the moon: I'm not quite sure where all the gravity went to.

It's disconcerting, having to make up a story, but it is mostly incredibly

liberating and fun."

Various kinds of journal writing, including the memoir, have been suggested as a

way to access creativity. Julia Cameron ("The Artist's Way") advises writing "three

pages, longhand and stream-of consciousness, first thing in the morning" as a "form

of meditation" and "spiritual windshield wipers."

Many

writers and therapists commend journaling as an effective strategy for healing

and personal growth.

This

form of writing may also have additional benefits: recent studies by

psychologists and immunologists have demonstrated that subjects who wrote "thoughtfully

and emotionally about traumatic experiences" showed increased T-cell production;

a drop in physician visits and generally improved physical health.

Ashworth found some writing of the book challenging in terms of just living her

life as an adult, but confirms it has been a positive and creative act overall,

"I

wrote this book partly because I had itchy fingers, and wanted to write other

things, and didn't want them to be polluted by the past. But also because, quite

simply, I thought I would go mad if I didn't. It's made a huge difference."

"I

have to say that the catharsis of writing it was painful and messy," she

continues. "And there were times during the writing of it when I'd be so

immersed in the past: I'd have to call up friends and say, sorry, I can't come

out tonight because I'm only nine years old. I couldn't go out and do the normal,

sort of grown-up things, I felt so trapped.

"When

I finished writing it, instead of feeling elated and liberated, in fact I felt

very burdened by this thing in front of me. I had to confront the gap between

this beautiful thing I wanted to write, and the thing I had written.

"It

wasn't until the book was published and read, and people started responding to

it and to me, that I began to appreciate the book's beauty, and began to feel

more friendly toward it.

"That's

been the catharsis, in fact, having the book read and shared with people who

have, or have not, the same kinds of experiences. I get thousands of letters,

and only about a quarter, if that, are from people who have suffered anything

really comparable; other people find other things in there, and others identify

with the happier and funnier aspects of it. It was hard, of course, but I tried

to write the book with a lot of buoyancy and fizz and color."

Ashworth adds more about her drive to write: "When I was a teenager, and felt

trapped and so on, there were no role models and nothing for me grab onto. So

partly I wrote the book with that sort of invisible audience in mind. And the

great thing is that in England the book is reaching lots and lots of children,

and I've been doing a lot of things to stimulate the truth and creativity in

children.

"I

think that's incredibly important. And it's a really vital, and fun, cause. I do

things like short story competitions, and guest editing magazines for children,

and so on. All that is incredibly therapeutic for me. That's really where the

recycling has happened, the feedback.

"In

America I've done these sorts of things only in a very localized way, with a

couple of libraries and so on. But I am getting feedback that some teachers are

picking it up, and introducing it to students. In England, it's actually getting

into the curriculum."

Writing her book, Ashworth affirms, "Exorcised the ghosts, but also exercised my

creativity. Memoir is still a pretty fresh and new form in England. When I wrote

it, there wasn't a tradition, it wasn't established, so it was very new. Though

in America that's not the case.

"Although

I'm now a novelist, I've discovered that in the past couple of years, talking

about the book (and I've traveled all over the world, and people in strange

countries respond to my work, which is very thrilling), everyone wants to know 'what

happened next.'

"Including

my mother, although she obviously knows - she wants to carry on reading. And

partly because I now feel safe and confident and happy enough talking and

thinking about my past, I would like to pick up from the moment when I arrive at

Oxford.

"Again,

it will be a true story, but in a kind of entertaining fictional mode. I want to

pick up sort of how a person recreates herself. Because everbody does that when

they leave home anyway. But how do you do that when you were nearly destroyed at

home?

"I do

want to go back to it, but I won't until I finish this novel, and I'm working on

some more short stories, too. So I will do it at some point in the next couple

of years. I'm actually looking forward to it."

When I was a little girl

This week a survey found

that 1m British children suffer violence at home. Author Andrea Ashworth, who

was abused as a child, is at least glad it's out in the open

Wednesday November 22, 2000

The Guardian

When I was a little girl, my mother wore sunglasses a lot

of the time - even when it was raining. Under the glasses, her skin would be

swollen and sometimes cut. My sisters and I watched each bruise go through its

sickening rainbow - scarlet, purple and yellow, green, black and blue - before

her face was itself again.

My father had drowned when I was five years old,

my little sister three. My mother married a new man, with whom she had a baby,

and from that moment we lived in a terrifying, topsy-turvy world. My stepfather

would hit us, about the head and in the face, for any reason or no reason at all:

a splash of spilled water, a misplaced sock, even the sight of my sister or me

reading a book. Occasionally, when he was especially careless, I would be thrown

into a concussion. If my mother cried or tried to stop our stepfather from

hurting us, he would turn on her. We regularly saw our mother being throttled,

punched in the face, hurled against the wall or the floor and threatened with

boiling water and knives.

After each explosion, my stepfather would thrust

his hand over my face until I gagged. He whispered foul, graphic threats to let

me know just what he would do if ever I, the eldest child, opened my mouth to

tell. He made me terrified of confiding in my own mother about his private

assaults on me. I never dreamed of telling the world what went on behind our

stripy green curtains.

At school, my nickname was Smiler. I scooted

around the playground, a vivacious child, giving my teachers no cause for

concern. Even without my stepfather's threats and the clamp of his hand over my

mouth, I would not have dared - back then - to appeal to a teacher or any

"outsider" for help. I put my smile on, over the secrets, and waited for it to

be knocked off again when I went home.

Why? Why didn't I say a word?

In the first place, although my sisters and I

lived in daily terror, it never occurred to me that we could, or even should,

expect anything different. Children can be marvellously, but also dangerously,

elastic, adapting to adversity, growing to regard it as normal. As I grew up, I

began to realise that what went on in my family was not normal but quite

horrific. Seeing this, I was struck dumb by a deep sense of shame. Domestic

abuse was not, in the 70s and early 80s, something to be discussed in public. I

had never even heard of terms such as neglect or abuse, let alone imagined them

being applied to my family. Moreover my mother and sisters and I suffered a

sense of guilt about what was done to us, as if we deserved it. Like many

victims, we were caught in a web of silence, woven from sticky strands of guilt

and fear, desperate hope, shame and, stickiest of all, love.

Just before I left home at the age of 18, I

climbed into a tiny aeroplane, took off into the clouds and turned green, going

through loop-the-loops and barrel rolls on a sponsored aerobatic flight that

helped to raise money for the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to

Children. I wasn't sure why I was doing it, why I had chosen to support that

cause, what that cause was exactly. I puked my insides out on the third loop and

came down giggling, feeling drunk. I was still someone behind whose big smile

lurked an agonising story.

Suffering in silence, my family and I went

through experiences that are, in all ways, unspeakable. This shroud of silence,

psychologically suffocating and literally lethal, was - and is - one of the most

insidious aspects of domestic abuse. Especially for children whose voices are

small. The NSPCC's latest survey reveals that child abuse is, as we ought to

have known, and cared about, all along, shockingly widespread. Children

desperately need to be rescued from daily torment and from futures in which they

will recycle mental, physical and sexual abuse, painfully reliving it, and

passing it on.

Thanks to the passionate and messy work of

charities like the NSPCC, thanks to a salutary swing in the media's searchlights,

thanks to our efforts to look at and understand ourselves as a society, stories

like mine are no longer so shamefully suppressed. Families do not have to fester

in secret. Smashing the silence is a crucial first step in smashing a cycle that

we have lived with too quietly, too long.

1.

I always feel it whenever I go

back to Manchester, this feeling in my tummy, it's as though there's this jigsaw

being worked out, down there, trying to figure out exactly what happened and why,

and also what will I find when I get there. I thought that what went on inside

my house was normal, I knew it wasn't good and I knew it was awful but I thought

that it was only to be expected. And I knew that if I spoke up and let on to

anybody outside the house what was going on, then my stepfather would explode

even more violently.

Growing up in inner-city Manchester in the Seventies and Eighties was a hairy

time for my sister and me because we were darker and so we were victims of a lot

of racism. The most disturbing kind of racism that we experienced came from

right inside the house. My father was half-Italian and half-Maltese and he died.

My step-father was white and he would refer to our dead father and to my sister

and me as 'wogs' and 'pakis' and so on, and in the street these were the same

sort of names that were thrown at us. That cliché, 'Behind closed doors' was

only too real in our house because as soon as the front door closed and the

curtains were drawn, awful things could go on.

2.

Sometimes my sisters and I

would run for the police, often barefoot and shredding the souls of our feet.

The police would come and my mother and stepfather would have covered everything

up and the police were only too happy to pretend that it hadn't happened too.

They'd leave and as soon as the door was closed behind them, my stepfather would

attack my mother even more.

Well, we moved around so much that most of our photographs were lost but those

that we did keep, my mother would hack with the scissors when one father went

out of our lives and another person was coming in. My mother would cut out the

head of the old man so that the new one wouldn't become irate.

There was a phase when we were especially low, when we had very little money and

often didn't have enough to eat. We found ourselves camping as a whole family in

a single room and sleeping on bare boards with black bin bags sellotaped across

the windows to serve as curtains. And constantly moving from one place to

another and unrolling the sleeping bag in a fresh place. My mum used to refer to

us as 'the three sausage rolls'. And I remember always feeling this sort of hole,

this sort of sloshing watery feeling in my tummy because we were hungry when we

went to bed and my mother would give us water to try and fill up in that way.

3.

I used to write endless love

poems to my mum: 'Dear mummy, I love you more than mashed potato, more even than

God'. And I'd fill these poems with all the most beautiful things I could think

of like birds and rainbows especially, so, from the very beginning, I knew she

was this complex, quite awesome spirit.

When my second stepfather came on the scene my mother came back to life - her

hair and her eyes would glisten again and she'd make jokes and have a wonderful

sense of humour. And we all adored him. When he was around, music would be

playing all the time and the house would just feel alive. When my mother was

happy, she'd put on motown records and after she'd finished the cleaning, she'd

get all dressed up then sing into her spiky hairbrush.

There'd be a period of honeymoon, when things seemed to be going well. And then

something would go wrong and suddenly, it would be a downward spiral. It was

truly shocking to realise that my mother was trapped in a cycle that was bad for

her and bad for us. It was after my second step-father had first attacked my

mother that I began to wonder what was going on and whether what was happening

wasn't just to do with one nasty ogre of a man and might have something to do

with my mother. I remember seeing this tiny little bruise, cherry shaped and

almost pretty, on her face and my instinct as an eleven-year-old child was not

to ask because I was afraid of what the answer might be. Nobody said anything

and I think that's because when I was growing up in the Seventies and even in

the Eighties, people didn't talk about domestic violence and it was a phrase I

had to get used to much later. It was something that was hushed up and as a

community I think, maybe we were ashamed of it.

4.

School was a real sanctuary. I

always hated going to school just because I hated leaving my mother at home and

would wonder and worry about her all day, but I adored school because there, the

rules were predictable. School was strict but you knew what was right and what

was wrong. It wasn't until I had got away from Manchester, had gone to Oxford

and then gone on to Yale, that I had the lethal luxury of time and distance to

think about the past and to look back and think, what happened, and moreover,

how did I survive that. And it was really that impetus that made me sit down and

start writing.

One of the things that I thought was important was for people to be able to read

Once in a House on Fire and take away from it a real sense of hope which

is what sustained all of us and what helped all of us to get on and get out. And

that's why I called it Once in a House on Fire, because I wanted it to

have a poetic and lyrical aura, a sense of a fairytale, albeit a badly

screwed-up fairytale, but one with a happy ending.