12-4-2003

|

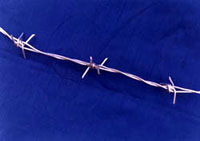

Arame farpado

fil (de fer)

barbelé

alambre de

púas

filferro amb pues

der

Stacheldraht

filo (di ferro

) spinato

taggtråd

piggtråd

pigtraad

piikkilanka

ostnaty drot

barbdwajer

bodljikava žica

Dikenli Tel

תיל דוקרני

刺鉄線 |

|

barbed wire

sârmă ghimpată

prikkeldraad

drut kolczasty

szögesdrót

колючая проволока

okastraat

dzeloņstieple

spygliuota viela

αγκαθωτό σύρμα

ostnatý drát

bodečo

žico

бодликава жица

бодлива тел

سلك شائك

鐵絲網 |

September 27, 2015

The tangled history of barbed wire

By Robert Zaretsky

EARLIER THIS MONTH,

the Hungarian government, scrambling to seal its southern border against the

influx of North African and Middle Eastern refugees trying to reach Germany,

placed a bid for 10,000 rolls of razor wire. Though the deal was worth hundreds

of thousands of euros, a German manufacturer, Mutanox, wouldn’t sell to the

Hungarians. “Razor wire is designed to prevent criminal acts, like a burglary,”

explained the company spokesman. “Fleeing children and adults are not

criminals.”

Had you doubts about the cunning of history, lay them to rest. From Germany’s

welcoming of refugees to its outrage at Hungary’s violent efforts to stop them,

the country that, 75 years ago, made barbed wire into the symbol of man’s

inhumanity to man has done much to overcome its past.

Yet, the Mutanox spokesman did not fully uncoil the history of barbed wire.

Contrary to his claim, one of the hallmarks of our age is that fleeing children

and adults have often been considered criminals. Entire peoples, by dint of

their race, religion, or social class, have been judged as standing outside

either the law or humanity. Stretching between them and us, figuratively and

literally, has been barbed wire, whose history tells us much about the plight of

today’s refugees.

Like inventors from Joseph Guillotin to Alfred Nobel, whose creations escaped

their original purpose and were yoked to evil ends, Joseph Glidden would have

been shocked at what became of his. In 1874, the Illinois farmer and New

Hampshire native, fastening sharpened metal knots along thick threads of steel,

created barbed wire. Thanks to its high resilience and low cost, the rapid

installation of the coils and lasting dissuasion of the barbs, the wire

transformed the American West. Ranchers could protect their cattle against

predators, both wild and human, as they pushed the frontier ever further west.

The wire itself came to be called “devil’s rope.”

The results were deep and lasting. As Dempsey Rae, the scarred cowboy played by

Kirk Douglas in “Man Without a Star,” declared about the wire: “I don’t like it

or the people who use it.” More real and tragic than disgruntled cowboys intent

on their freedom, however, was the fate of the Native Americans. They were not

jailed behind barbed wire outright, but the Dawes Act allowed all “excess” land

not claimed by individual Native Americans to be sold to ranchers, who

immediately enclosed their lands with barbed wire, thus crippling the

traditional migration and hunting patterns of the tribes. But as the world

discovered quickly, they were not the last.

Scarcely a decade later, the Boer War, fought between the British Army and Dutch

settlers in South Africa, revealed the striking military uses of Glidden’s

invention. The British stretched hundreds of miles of wire, punctuated by

guardhouses, along their rail lines to shield them against Boer attacks. By

dicing and slicing the African veld with wire, the British made a great advance

in the long struggle to prevent the movement of animals or fellow human beings

over land we claimed as ours.

Not

coincidentally, South Africa was also the birthplace of the modern concentration

camp — the

demarcation of space by barbed wire, but this time to keep people in and not

out. When the British rounded up families from their farms and villages to

throttle support, material and logistical, for the commandos, they needed to

build camps for the civilians as quickly and cheaply as possible. Barbed wire

was as versatile as duct tape: ideal for a thousand different emergencies, only

all of them far more insidious. The British turned to barbed wire to serve as

the walls for the camps where the civilians were relocated. Though they soon

became breeding grounds for disease and despair, these camps, were devoted to

the control, not demolition of a people. Nevertheless they gave not only a name,

but also a blueprint to the camps that erupted across the European continent in

the decades to come.

Before the camps, though, came the trenches. Barbed wire frames the lunar

landscape of World War I.

Oddly, Kirk Douglas again serves as our guide. Just as he is scarred and

defeated by barbed wire in “Man Without a Star,” in “Paths of Glory” he must

submit to it as Colonel Dax, ordered to attack an impregnable German gun

position. To respond to the unprecedented situation on the Western Front, where

the usual war of movement had coagulated into a static line stretching from the

English Channel to Switzerland, barbed wire was heaven-sent. Or, more

accurately, US Steel sent. The company produced nearly 3 million miles of barbed

wire during World War I.

It was a cheap, rapid, and effective means to stop the movement of large forces

of men bent on your destruction. When combined with another recent invention,

the machine gun, barbed wire became more imposing than the largest fort or

cannon. As advancing soldiers on both sides quickly discovered, the massive

bombardments that preceded their attacks might have leveled a fortress, but was

mostly useless against barbed wire.

Had he starred in a movie about the Holocaust, Douglas would have hit

modernity’s trifecta, completing a kind of barbed wire trilogy. Barbed wire, an

accessory to earlier wars, stars in WWII. The French philosopher Olivier Razac

observes that when we see a photo of barbed wire, we tend not to associate it

with prairies or trenches, the American West in the 19th century or European

West in the early 20th century. Instead, we reflexively associate it with the

European East — baptized the “bloodlands” by historian Timothy Snyder — and the

death camps to which they were home.

How could it be otherwise? Imagining himself back at Auschwitz, Primo Levi gazed

at our everyday moral world. How much of it, he wondered, “could survive on this

side of the barbed wire.” Not much, we learned. How extraordinary that so simple

a thing — a bit of sharpness suspended in air — could carry such tremendous

meaning. Yet come the Holocaust, as the philosopher Reviel Netz observes, barbed

wire embodied the asymmetry between an all-powerful state and utterly powerless

mass of people. In a sense, “the concentration camp system was a recapitulation

of the animal industry, now a human industry . . . bringing the ecology of flesh

and iron in the age of barbed wire to its culmination.”

As history since Auschwitz reveals, barbed wire is the infernal gift that keeps

giving. From Siberia to Srebrenica, Glidden’s invention proved its functional

and symbolic resilience, one that now inescapably shapes our understanding of

today’s refugee crisis. A day hardly passes that a front page or magazine cover

does not frame a photo of migrants from Syria and Iraq, Afghanistan and Eritrea,

pressed against barbed wire barriers along Europe’s frontiers. Familiar with the

iconic shots of the Bergen-Belsen or Bosnian camps, we might tell ourselves that

the photos of today’s migrants are somewhat misleading. These men, women, and

children are not, strictly speaking, penned in concentration camps, much less

death camps.

But that is strictly speaking. It does not take a great stretch of moral

imagination to portray great swaths of North Africa and the Middle East as one

vast concentration camp. It is a region where suffering, disease, and despair

are the rule — a camp whose walls of barbed wire have been strung up not by the

failing and murderous governments inside, but rather by us along its edges. The

barbed wire fences uncoiling in France and Hungary, Italy and Greece are not

keeping undesirable elements outside of Europe. Instead, they are keeping those

same elements inside zones where death, not life, is commonplace.

From the concentration camps of South Africa to the death camps of Nazi Germany,

from the trenches of northern France to the tundra of eastern Russia, the

collective memory of the 20th century has a texture. It is one as hard and cold

as steel — wiry steel punctuated with razor-sharp knots — now stretching into

this still new century. Primo Levi asked how long our moral world would last

inside the fences of Auschwitz? As refugees continue to flee to Europe, the

question needs to be inverted: How long can our moral world survive as we stand

and watch them from outside the barbed wire?

Robert Zaretsky is a professor at the University of Houston and is author most

recently of “Boswell’s Enlightenment.”

"Barbed

Wire: A Political History" by Olivier Razac

Here's how a simple twist of spiked metal ravaged the

American West, crucified a generation of young men and terrorized millions of

Europeans.

By Damien Cave

Aug. 6, 2002 |

In a world jampacked with stuff for the body, house, car,

government or corporation, one can only survive through selective awareness.

Paying full and serious intellectual attention to everything from the microwave

to the beer-can cozy simply isn't possible. Just imagine how hard it would be to

get anything done at work if you couldn't type without ruminating on the letter

arrangement of the modern keyboard. Why is the "P," a relatively popular letter,

so hard to reach? Who decided that the "I" didn't belong between "H" and "J"?

Was it always this way? (As a matter of fact it was. Early keyboards were

designed to slow down typists, whose fingers moved so fast they jammed the

mechanisms of the old manual typewriters.)

These are just a few of the

questions that would get you fired if you couldn't survive without having them

answered. And yet, to completely forget how we have shaped and been affected by

the various things that surround us amounts to ignorance. Many of the modern

products we regularly overlook -- plastic trash bags, to take a more trivial

example -- have dramatically altered the nature of our society. They are parts

of the honeycomb we've built to make life easier, cleaner or better-looking.

Because they envelop and reflect us, they deserve to be analyzed and discussed.

Seinfeld's writers understood

this. Authors and book publishers have also made a habit of identifying

significant items and holding them up to the light of intelligent study. In the

past few years alone, air conditioning, wristwatches, guns, steel and even the

color mauve have all been subjected to literary scrutiny.

Now, barbed wire can be added

to the list. Olivier Razac, a Ph.D. candidate in philosophy at the University of

Paris, has written a short history of the metal fencing and how it's been used

through three periods: the settling of the American prairie at the turn of the

19th century, World War I and World War II, specifically in concentration camps.

The result -- "Barbed Wire: A Political History" -- may fall short of a complete

and thorough exegesis on all things wiry and barbed. In fact, Razac's slim,

often repetitive book will leave the curious hungry for more. But with its

pictures, quotes from primary sources and expansive prose, "Barbed Wire" offers

more than enough insight to be worthy of a focused read.

Razac's primary goal is to

prove that barbed wire has been used repeatedly for "the political management of

space." He points out that barbed wire began in the world of agriculture. J.F.

Glidden, an Illinois farmer, patented the design -- a pair of metal wires

twisted to hold a barb in place -- in 1874 as a means of keeping wild animals

from private land. But barbed wire was also far cheaper than other forms of

fence and it hit the market just as American settlers fanned out across the

great plains.

Thus, it became the boundary

enforcer of choice, the fence that appeared in places that had otherwise been

left unmarked. Steel makers benefited substantially: About 270 tons of barbed

wire were produced in 1875; by 1901, that number had shot up to 135,000 tons.

The problem, of course, was that the newly cordoned-off lands were not

unoccupied. Native American tribes had been roaming the plains for generations

-- and they had no reverence for the private ownership that barbed wire

protected. To them, the spiked metal barrier was not a new fancy fence but

rather a tool of subjugation. It was a cultural weapon that single-handedly

altered their daily existence. The buffalo and bison that they hunted no longer

had the same freedom to roam; the tribes no longer had the same freedom to hunt.

Most Native Americans decided

to flee barbed wire rather than fight its spread, but eventually they had

nowhere to go. Barbed wire dominated the once-open landscape, surrounded tribal

areas and eventually destroyed the communal nature of their society. "In short,"

Razac argues, "it created the conditions for the physical and cultural

disappearance of the Indian."

Historians might want to

point out that other factors did far more damage to Native American life than

barbed wire. Guns, greedy settlers and the ignorant Manifest Destiny belief that

white Europeans deserved the land from coast to coast -- these all significantly

contributed to the Native American "disappearance," though you wouldn't know it

from reading "Barbed Wire." Still, Razac is correct to point out that barbed

wire severely affected Native American life.

He's also correct to note

that this wasn't the last time that barbed wire became an implement of war.

During World War I, for example, barbed wire became as common as the trenches it

protected. With up to 19 barbs per meter as opposed to the seven spikes found on

Glidden's design, the wartime wire tended to be more dangerous. It was an ideal

form of defense -- invisible from afar, immune to artillery, easily fixed or

replaced -- and every army made wide use of it. But barbed wire also created new

kinds of casualties and psychological harms. People who died in barbed wire near

the trenches often remained there as immobile, pungent symbols of war. They

became "fish in a net," Razac points out, and for many soldiers, the sight of

such corpses was just too much. They often risked their lives to unhook a dead

comrade.

But the most telling example

of barbed wire's violent political uses and effects came in World War II. The

Nazis made barbed wire a staple of their cold, cruel organization. It appeared

in the cities that they conquered as a way to manage and ghettoize the defeated,

and in concentration camps. Indeed, these ghastly cities of death couldn't have

existed without barbed wire. At Buchenwald and other camps, the fences were the

first structure built and the most vital, Razac reports. They separated women

from men, Jews from other prisoners -- and everyone inside from the Nazi

officers and outside world. It was an electrified "burning frontier," as one

prisoner put it, which acted a constant, horrible reminder of Nazi power. "Everywhere

was the sinister tight iron grip," wrote Primo Levi, who Razac quotes at length.

"We never saw where the barbed wire fences ended, but we felt their malign

presence which separated us from the world."

Because the Nazis made such

strong use of barbed wire, Razac argues, it has become "the symbol of the worst

catastrophe of the century." A picture of barbed wire alone conjures up images

of extreme captivity and pain. Those who live behind barbed wire know that they

are somehow less than human; beasts who are to be worked, removed or slaughtered.

More than any other barrier, Razac writes "[barbed wire] has become a graphic

symbol for incarceration and political violence."

It's hard to disagree with

such an assertion. Who hasn't seen barbed wire and been afraid of what lies

behind it? But where Razac goes wrong is in assuming that this was purely the

result of his three chosen examples. Even if barbed wire had nothing to do with

the Native American diaspora or World War I, and even if the Nazis never used it

for concentration camps, barbed wire would still symbolize a loss of freedom.

This is because it's so ubiquitous. Traditional prisons have been using barbed

wire for generations. Old factories and anything else with "No Trespassing"

signs are also fenced off with gobs of tangled barbed wire. At this point, the

public's association with barbed wire is more closely aligned with a clear and

present physical or legal danger than with an old form of political or wartime

violence.

And yet, this conventional

association is exactly why "Barbed Wire" is a fascinating read. Sure, there are

serious flaws. Razac spends far too much time emphasizing the psychological

effects of barbed wire and not nearly enough time showing how it has spread and

developed. His prose tends to be too academic and the chapter linking barbed

wire to today's more modern forms of virtual surveillance is an unwarranted

stretch that should have been avoided. But Razac's book ultimately succeeds

because it manages to cast barbed wire in an entirely new light. By reminding us

all that barbed wire has been used as a political force, Razac has made an old

item new. No one who reads "Barbed Wire" will look at the stuff the same way

again. And while this may be only a minor achievement -- other authors have done

a better job bringing an old, overlooked item up to date -- it's still a task

that deserves to be lauded.

About the writer

Damien Cave is a senior writer for Salon.

Bouquet of thorns

Nigel Fountain wrestles

with cultural histories of barbed wire from Alan Krell and Oliver Razac

Saturday December 14, 2002

The Guardian

The Devil's Rope: A Cultural History Of Barbed Wire

by Alan Krell

222pp, Reaktion Books, £16.95

Barbed Wire: A Political

History

by Oliver Razac

translated by Jonathan Kneight

148pp, Profile Books, £6.99

|

Contemplating these works,

I assessed my own barbed wire reference points. The other month it was

blundering around some Cotswolds fields and, having noted some

malign-looking cows - there was a horse hanging around too - legging it over

a barbed-wire fence, ripping my thumb and being spotted by the owner's

public school son.

"Can I help?" were his

words. Alan Krell, a Australian art historian and theorist, who does

semiology in a big, indeed wearisome, way, could have assisted then with

some signifiers. But the youth's message was clear. Evacuate our space, town

scruff. I needed no help, I announced, but displayed my finger, oozing blood.

"Doesn't look serious," he said. |

|

|

|

Enclosing is a political act,

as the Parisian philosopher Oliver Razac explains, which "marks out the

boundaries of private property, assists in the effective management of land, and

makes social distinctions concrete". These Gloucestershire gentry further

underlined their distinctions by merging their barbed wiring into upmarket

woodwork.

Understandable really; by

1945, as Parisian philosopher Razac points out in his engrossing work, barbed

wire was already beginning to be seen as outdated - and, after two world wars

and the Nazi concentration camps, "an almost universal symbol of oppression".

Nowadays western liberal democracy really does like it out of sight, if not out

of planning mind.

It was low production costs

that got the stuff up and running across the north American prairies from the

1870s. Krell mentions a predecessor, the "live fence" of the thorny Osage orange,

but barbed wire didn't have to be grown or encouraged: it came out of factories

like those of IL Ellwood & Co "manufacturers of the Glidden Steel Barb Fence

Wire" in DeKalb, Illinois.

Barbed wire and the iron horse

sealed the fate of Native American civilisation. No more

world-belongs-to-everyone hokum; instead, property in, intruders, particularly

wide-ranging Native Americans, out. The lightweight wonder of barbed wire helped

in the mass-production of wealth - while discarding the wrong animals and the

wrong human beings. The United States was inclusive, welcoming indeed, to most

who accepted its rules. The people of the great plains, who could not, retreated,

but still found their space cut off by barbed wire and their communal societies

ripped apart by it, so what had been their land was transformed into a foreign

country and, when all the land ran out, they fell off it.

Razac's book hangs on three

case studies; the American west, the first world war, and the Nazi camps of

1933-45. Krell dwells on Kitchener's remorseless use of barbed wire in the South

African war - Kitchener used it to pen in and cut off the Boers - but it was on

the western front (and the eastern front too, but Razac the Frenchman focuses on

les Poilus) that barbed wire, the agricultural tool, alongside long-range

artillery and rapid-fire guns came into its own in the herding and destruction

of human beings. No man's land, framed in the barbed wire which was itself a

fishing net for corpses, provided a lasting tableau of the advance of industrial

society since the pioneer days of IL Ellwood & Co. But, adds Razac, in the first

world war the wire was only part of the aesthetic. The Nazi genocide was to be

symbolised by the wire.

Concentration and

extermination camps started with the fences, then progressed to further horror.

The camps became "the physical realisation of the totalitarian dream, a society

of total domination" with space shaped in wire.

Unfashionable wire may now be,

but some pressing new use for it is always popping up, as Camp X-Ray splendidly

demonstrates. And there are always new forms. Razor wire, Krell's book claims,

is a bequest from apartheid South Africa; how touched those starving 1900s Boers

would have been.

Razac's postcard-sized book is

invigorating. Krell is occasionally interesting, but when he labels three

concentration camp survivors, in a 1945 photograph, "nascent visual tropes of

Nazi persecution", words have failed.

Nigel Fountain edited The

Battle of Britain and the Blitz and Women at War (Michael O'Mara)

Boston’s Weekly Dig

Barbed Wire : A Political

History

Olivier Razac, Translated by

Jonathan Kneight (The New Press)

by

Jess Collins

Despite its almost ridiculous

simplicity in the context of the modern era, the invention of barbed wire had

surprisingly profound implications. A simple design fashioned from an abundant

and cheap material, it is nevertheless one of the most durable and effective

means of dividing and controlling space and people. With short essays on three

historical uses of barbed wire, French scholar Olivier Razac illustrates how it

became one of the most powerful political tools of the past 100-plus years.

With its advent in the late 1800s by a midwestern farmer, barbed wire quickly

proved an important aid in conquering the American West. Not only was it useful

in dividing land for farming and the herding of animals, but the control it

allowed white settlers over what had been Native American territories was

instrumental in their final dominance. Severing the plains physically meant

severing Native Americans from each other, dissolving their tribal strength and

their connection to the open land. White settlers were able to physically cordon

off areas from native use, force their values of individualism onto the native

population and exploit the land for profit. From this powerful example of the

first political use of barbed wire, Razac goes on to explore its equally complex

and tragic uses in World War I trenches and in Nazi concentration camps. He also

dedicates several short, accessible essays to more theoretical considerations on

the political management of space.

With a focused narrative and a generous collection of photographs, Razac

explores how such a basic design complicates the horrors of war and genocide and

what the politics of space mean today. A quick, sharp, startling read, this

little book is itself like a cut: a simple and straightforward expression of

suffering and also a revealing glimpse at a complex world barely hidden beneath

a thin surface.

The Examiner

Publication date: 08/12/2002

A

slender, potent barrier

BY

JONATHON KEATS

Special To The Examiner

"There

were a lot of encampments and the hedges kept people out. People were living in

the square. It was a security issue."

-- designer April Philips on the challenge of rebuilding

Union Square

|

The

American prairie didn't have a lot to offer an aspiring rancher in the 19th

century. The landscape was harsh, sturdy lumber was scarce and often even

rocks were too uncommon to fence in an acre of pasture. Then, in 1874, came

the invention of barbed wire.

Everything changed.

John Warne Gates, an early merchant, billed it "the best fence in the world.

As light as air. Stronger than whisky. Cheaper than dust." As Olivier Razac

ably demonstrates in "Barbed Wire: A Political History" (New Press; $22.95),

Gates couldn't even begin to imagine how effective that simple invention

would eventually prove.

In 1874, barbed wire

sold for $4.50 a pound, with just four pounds fencing in an acre. Within two

decades, the cost dropped to one 10th that. As might be expected, production

increased exponentially, from 270 tons in 1875 to 135,000 tons in 1901. The

frontier changed radically. Sedentary settlers replaced the free-ranging

cowboy. Far more troubling was the fact that Native Americans were corralled

almost into oblivion. |

|

|

|

The "political management

of space" is the true subject of Razac's brief study, and barbed wire serves

well as both historical example and forward-looking metaphor. "Among the modern

political devices of separation," he writes, "barbed wire becomes a tool of

extreme polarization." While the trenches in World War I and the Nazi

concentration camps both provide him with poignant examples, it's on the

American frontier that the lessons to be learned from barbed wire are most clear.

Barbed wire accomplished

the settlers' aims because so little did so much. Almost invisibly, it divvied

up the land, putting in sharply tangible terms the idea of private property,

expressing quite literally that territorial borders need not be seen for their

effect to be felt. "The cattle haven't been born that can get through it," John

Warne Gates claimed in his 19th century sales pitch. But more profound than that

was how it confined and conquered Native American culture.

"It chopped space into

little bits and broke up the communal structure of Indian society," Razac argues.

"Barbed wire made the Indians' geographical and social environment hostile to

them, so that it became a foreign territory where the tribal way of life was

unimaginable." Attempts at resistance were futile. Barbed wire was produced so

cheaply and in such quantity, and was repaired so easily, that any breach was

temporary: as insignificant as a single malefactor in the face of the law.

So the American frontier

was broken into pieces, each under individual control, all of which worked

together in a social fabric woven of barbed wire. Later, reservations were

enclosed as well, in which case the coercion of Native Americans came from

without rather than within. The ultimate irony: Their property, the land they

never wished to own, came to possess them, to have them in its hold like animals

on a farm.

The crucial point is that

all the stonework in the world, the sturdiest of walls most scrupulously

maintained, could not have won the West as simply as did a thin string of wire.

The reason is not practical but psychological. Vanishing from sight at distances

great enough to get the lay of the land, barbed wire made it appear that

authority was everywhere because, paradoxically, it seemed, almost, to be

nowhere.

As Razac notes, English

philosopher Jeremiah Bentham's legendary Panopticon had accomplished this, in

theory, a century earlier: He proposed a prison-in-the-round with a single guard

at its center, able to watch everybody but seen by nobody. An inmate never knew

if he was being observed. In effect, people would police themselves, and even if,

one day, there was no guard at all, it wouldn't make a bit of difference.

Of course, barbed wire

couldn't achieve that so-called ideal, but it suggested that the inverse

relationship between visibility and authority was real. The technology suggested

that an ever greater degree of subordination would come as barriers became ever

less substantial.

The supposition turns out

to be right, as can be seen in San Francisco's own Union Square. There's no gate

that can be crashed, no protective hedge in which to hide. Wide open, the space

is absolutely controlled, boundlessly closed to an "outsider."

Any of us could be

Bentham's guard. Does that, though, make all of us his prisoners?

The Angry Corrie 56: Jan-Mar 2003

few barbed comments: Barbed Wire: A History, by

Olivier Razac

(translated from the French by Jonathan Kneight),

Review: Ann and Rowland Bowker

|

The hillwalker's first thoughts on seeing a

fence looming ahead is to wonder if it will be topped with barbed wire. If

not it is usually easily surmounted, but otherwise out come the old

fertiliser bags carried especially for this purpose. Judicious use thereof

is usually enough to facilitate an injury-free passage. No doubt male

walkers have more to lose from a careless crossing - but if, as the latest

glossy mags suggest, the hills are now peopled largely by glamorous

fashion-conscious bunny girls then the thought of ripping one's

designer-label trousers may be just as dreadful as that of damaging vital

body parts.

As old age brings diminished agility we find

such obstacles more of a problem and so were very interested to read a book

on the history of the horrible stuff - which, it tells us, was invented in

1874 as a way of fencing the prairies. |

|

Barbed wire at Dachau |

|

Razac concentrates on three particular

applications of barbed wire. Its use in concentration camps is well known, a

horror reiterated here. One has read this so many times that perhaps it loses

some of its power to shock. But tellingly this English translation (from the

French published in 2000) includes, along with the faces looking out from

Auschwitz, a photograph taken on 6 February 2002 at Guantanamo Bay.

Equally horrifying are the scenes from the

trenches, this time describing the use of barbed wire to delimit no man's land

and putting a new emphasis on the futility of war and its impact on the ordinary

soldier.

But it is the original function of the wire as a

means of claiming and confirming land ownership which will have the greatest

resonance with today's hillwalkers. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave any American

citizen the right to own 160 acres of land so long as it was cultivated. In

theory this right extended to the American Indians, but cultivation was entirely

alien to their culture and the fencing of the land prevented access to their

traditional hunting grounds. It was mainly this, rather than the battles of the

traditional movie, which drove the Indians westwards and eventually destroyed

their way of life completely.

This must surely invoke the sympathy of those of

us who find alien the concept of rights of way as corridors through the wide

empty spaces of the hills, fenced off by barbed wire or by some unwritten

rambler's code of conduct.

The second half of Barbed Wire: A History

to some extent repeats the thoughts invoked by the scenarios in the first half.

Barbed wire is used for both inclusion and exclusion. Those controlling the wire

create a space in which they and their friends and allies are included. The

prisoner is excluded from society and from a normal existence. The author makes

no attempt to discuss the question of when such exclusion might be justified

either to punish the prisoner or to protect society, a dilemma highlighted by

the inclusion of the Guantanamo picture.

As Razac points out, barbed wire without

surveillance is easily penetrated. There are few hills in Britain from which the

determined walker is excluded. Where fertiliser sacks fail then wire cutters can

be employed. In other countries exclusion may be more rigorous. There are many

mountain summits around the world crowned with closely guarded military

installations. There are places where the landowner may shoot unwanted visitors

and where PRIVATE notices are more than just dissuasion to the more timid walker.

Mount Whitney, highest summit in the contiguous USA, is one of many places where

access is rationed and by permit only. In areas that are well patrolled or

surveyed electronically the need for wire disappears.

The conclusion of this thought-provoking book is

rather disappointing, as Razac relapses into orthodox socialist rhetoric

suggesting that the main reason for exclusion might be economic inability to

contribute to the consumer society. Perhaps the book was written a few years too

early, because it does not look beyond the use of CCTV cameras to eliminate the

great unwashed and unwanted from shopping malls and exclusive housing estates.

It fails to mention the much greater threat from the GPS transmitter which may

soon be fitted in every car, not only able to detect speeding transgressions but

also capable of noting how long you have been parked suspiciously close to that

private hill.

The technology exists to implant a microchip in us

all and to record our every movement from birth to death. Some parents are

already seeking to do this to their children, ostensibly to protect their

cotton-wool kids from abduction.

The issues addressed in this book are just as

topical today as in the 19th century wild west and it should be read by everyone

who values their freedom to break through barriers, barbed or otherwise.

In These Times

Don't Fence Me In

By Neve

Gordon

6-12-2002

Have you ever thought about

the baby-bottle nipple and the extensive impact this small object has had on

society? Michel Foucault mentioned this simple innovation in an interview,

suggesting that it not only did away with the age-old profession of wet nurses,

but changed the lives of millions of mothers. In many ways, the plastic nipple

helped free women from their imprisonment in the private realm, while

facilitating the possibility of egalitarian parenthood.

In his Prison Notebooks,

Antonio Gramsci briefly discusses the tin can, asserting that among other things

it helped shape modern warfare. The novel capacity to stock up canned food in

the trench storerooms—months in advance—prolonged World War I and intensified

its horrific effects.

While materialist histories

of objects like the tin can and the plastic nipple have yet to be written,

Olivier Razac recently took it upon himself to chronicle the invention and use

of barbed wire. The book is written in both a luring and lucid fashion and is

illustrated with arresting American and European archival photographs.

--------------

In 1874, J.F. Glidden, an

Illinois farmer, took out a patent for the barbed iron wire he had invented, and

for a machine that would mass-produce it. He wanted to help new American farmers

assert property ownership over their land. Sure enough, as white newcomers moved

west, rapidly fencing off the prairie, the production of barbed wire shot up

from 270 tons in 1875 to 135,000 tons in 1901.

The 1887 Dawes Act authorized

the president to parcel out Indian land to white farmers. Simply by fencing in

their newly acquired plots, white farmers managed to enclose the Indians in

reservations, cutting them off from hunting grounds. Barbed wire, as Razac puts

it, “chopped space into little bits and broke up the communal structure of

Indian society ... [making] the Indian’s geographical and social environment

hostile to them, so that it became a foreign territory where the tribal way of

life was unimaginable and where nomadic wandering and hunting were impossible.

In short, it created the conditions for the physical and cultural disappearance

of the Indian.”

During the same period,

farmers employed the wire to defeat the cattle barons, in what was labeled the

“barbed wire wars.” In the Hollywood film Man Without a Star, the very

sight of barbed wire infuriates Kirk Douglas, who plays the archetypical cowboy

hero. “What’s the matter?” asks the farmer. “I don’t like it,” Douglas answers,

“or what it’s used for.” With the fencing in of the prairie, the cattle empire,

founded on free grazing, ultimately collapsed, and the lone cowboy riding over

the plains disappeared.

The lightness of the barbed

wire and the difficulty in spotting it converted the “bramble,” as it was

frequently called, into a tactical apparatus employed in the defensive structure

of World War I trenches. Easily repaired or replaced, barbed wire did away with

soaring thick walls, creating a network of entanglements that was a highly

efficient obstacle against the attack of enemy infantry. Combatants who were

caught in the wire were killed by rival fire. It is not coincidental that one of

the most vivid images from World War I is the corpse of a soldier entangled in

wire in the middle of no-man’s-land.

--------------

Barbed wire was also a

central element in the architectural design of the Nazi concentration camp. A

double fence of electrified barbed wire usually encircled the camp from the

outside, while a whole set of fences divided the inside, helping to produce the

totalitarian organization of space. “Everywhere,” Primo Levi wrote, “was the

sinister tight iron grip. We never saw where the barbed-wire fences ended, but

we felt their malign presence which separated us from the world.”

The wire also assisted in

shrouding the extermination project in a veil of secrecy. At the Sobibor and

Treblinka camps, the path leading to the gas chambers was camouflaged with

barbed-wire braided with branches. The use of barbed wire not only facilitated

the organization of space, but also this space’s swift erasure. None of the

concentration camps were built to last; most were constructed in such a way that

they could easily be dismantled and thus could disappear from sight and, as some

hoped, from memory. “It was there,” Razac points out, “but it was not there. It

was transient.”

Despite the Nazi attempt to

expunge their existence, the concentration camps helped turn the image of barbed

wire into a graphic symbol of captivity, political violence and death. Levi put

it this way: “Liberty. The breach in the barbed wire gave us a concrete image of

it.”

The book’s second part

provides a theoretical analysis of how barbed wire was employed to manage space.

Razac cogently argues that its use should be understood as both a sign and an

action. As a sign, barbed wire “produces a kind of shock when it is used to

enclose people, shaking their certitude that they are human. It confirms their

fate: like beasts, they are to be worked or slaughtered.”

As an action, barbed wire

excludes and includes. “Its function is always to magnify differences between

the inside and the outside.”

Razac employs Foucault’s

notion of “biopolitics,” the idea that in the 18th century governing began to

concern itself with life—rather than death—by using a variety of techniques to

manage the lives of its subjects. The author maintains that barbed wire was

successful in the United States because it coincided with the biopolitical needs

of the whites, while helping to destroy Indian society. Wittingly or unwittingly,

Barbed Wire offers a corrective to Foucault, for it shows that modern

biopolitics is often intricately tied to a thanatopolitics, the politics of

extermination and death.

But Razac’s theoretical

discussion is, in many ways, also disappointing. My major reservation has to do

with his attempt to conflate, rather than to distinguish, the different ways in

which barbed wire was employed to manage space. He argues that barbed wire was

used to separate “those who will live from those who will die,” while producing

a “distinction between those who are allowed to retain their humanity and those

reduced to mere bodies.”

While this analysis appears

accurate when thinking of the Nazi concentration camps, it does not ring true in

relation to World War I. It is precisely the diverse historical roles barbed

wire has played—both as sign and as action—in the modern process of separating

and homogenizing society that needs to be exposed, analyzed and explained.

Explicating and trying to

understand the continued widespread use of barbed wire could have added an

additional dimension to this fascinating book. For example, examining the

architectural similarity and differences between the camps Israel has

constructed to hold Palestinians and the concentration camps Jews were held in

during the Holocaust, urges one to ponder how it is that the reappearance of

barbed wire in the Israeli landscape does not engender an outcry among survivors.

Does this silence put into

question the symbolic power of barbed wire, or does it underscore that this

power is always limited by its own context? Questions like these could have

problematized Razac’s analysis, suggesting that the issues at hand are often

more complex than the book implies.

Neve Gordon teaches

politics at Ben-Gurion University, Israel, and can be reached at

ngordon@bgumail.bgu.ac.il.

The TLS n.º 5330

MAY 27, 2005

Twisted Logic

Edward N.

Luttwak

BARBED WIRE, An ecology of modernity

Reviel Netz 267pp.

| Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. $24.95; distributed in the UK by

Eurospan. £17.50. | 0 8195 6719

Barbed

wire is important in my life – the cattle ranch I run in the Bolivian Amazon

could not exist without it. In Britain as in other advanced countries, it is

mostly fences of thin unbarbed wire enlivened by a low-voltage current that keep

cattle from wandering off, but in the Bolivian Amazon they have no electrical

supply to transform down, and in any case the cost, over many perimeter miles,

would be prohibitive and the upkeep quite impossible. Ours is a wonderful land

of lush savannahs and virgin forest, but it is just not valuable enough to be

demarcated by anything more expensive than strands of barbed wire held up by

wooden posts driven into the ground.

Invented and patented by Joseph F. Glidden in 1874, an immediate success in mass

production by 1876, barbed wire, first of iron and then steel, did much to

transform the American West, before doing the same in other prairie lands from

Argentina to Australia. Actually, cheap fencing transformed the primordial

business of cattle-raising itself. Solid wooden fences or even stone walls can

be economical enough for intensive animal husbandry, in which milk and traction

as well as meat are obtained by constant labour in stable and field to feed

herbivores without the pastures they would otherwise need. Often the animals are

tethered or just guarded, without any fences or walls. But in large-scale

raising on the prairie or savannah, if there are no fences then the cattle must

be herded, and that requires constant vigilance to resist the herbivore instinct

of drifting off to feed – and also constant motion. As the animals eat up the

vegetation where they are gathered, the entire herd must be kept moving to find

more. That is what still happens in the African savannah of the cattle herdsmen,

and what was done in the American West as in other New World prairies, until

barbed wire arrived to make ranching possible.

One material difference between ranging in open country and ranching is that

less labour is needed, because there is less need for vigilance within the

fence. Another measurable difference is that cattle can do more feeding to put

on weight, instead of losing weight when driven from place to place. But the

increased productivity of ranching as opposed to ranging is actually of an

entirely different order. African herders must be warriors to protect their

cattle from their like as well as from the waning number of animal predators,

but chiefly to maintain their reputation for violence which in turn assures

their claim to the successive pastures they must have through the seasons. It

was almost the same for the ranging cowboys of the American West, and while

their own warrior culture was somewhat less picturesque than that of the Nuer or

Turkana, it too was replete with the wasted energies of endemic conflict over

land, water and sometimes even the cattle itself. Ranchers are not cream puffs

either, but they can use their energies more productively because in most places

– including the Bolivian Amazon for all its wild remoteness – their fences are

property lines secured by the apparatus of the law, which itself can function

far more easily among property-owning ranchers than among warrior nomads and

rangers. Skills too are different. African herdsmen notoriously love their

cattle to perdition but their expertise is all in the finding of pasture and

water in semi-arid lands, as well as in hunting and war, and they are not much

good at increasing fertility, and hardly try to improve breeds. It was the same

in the American West, where the inception of today’s highly elaborate

cattle-raising expertise that makes red meat excessively cheap had to await the

stability of ranching, and the replacement of the intrepid ranger by the more

productive cowboy.

Barbed wire is important therefore, and the story of how it was so quickly

produced by automatic machines on the largest scale, efficiently distributed to

customers necessarily remote from urban centres, marketed globally almost

immediately, and finally used to change landscapes and societies, is certainly

very interesting. But for all this, the reader will have to turn to Henry D. and

Frances T. McCallum’s The Wire That Fenced the West rather than the work at

hand, in spite of its enthusiastic dust-jacket encomia from Noam Chomsky (“a

deeply disturbing picture of how the modern world evolved”), Paul F. Starrs

(“beautifully grim”) and Lori Gruen, for whom the book is all about “structures

of power and violence”. The reason is that Reviel Netz, the author of Barbed

Wire: An ecology of modernity, prefers to write of other things.

For Netz, the raising of cattle is not about producing meat and hides from lands

usually too marginal to yield arable crops, but rather an expression of the urge

to exercise power: “What is control over animals? This has two senses, a human

gain, and an animal deprivation”. To tell the truth, I had never even pondered

this grave question, let alone imagined how profound the answer could be. While

that is the acquisitive purpose of barbed wire, for Professor Netz it is equally

– and perhaps even more – a perversely disinterested expression of the urge to

inflict pain, “the simple and unchanging equation of flesh and iron”, another

majestic phrase, though I am not sure if equation is quite the right word. But

if that is our ulterior motive, then those of us who rely on barbed- wire

fencing for our jollies are condemned to be disappointed, because cattle does

not keep running into it, suffering bloody injury and pain for us to gloat over,

but instead invisibly learns at the youngest age to avoid the barbs by simply

staying clear of the fence. Fortunately we still have branding, “a major

component of the culture of the West” and of the South too, because in Bolivia

we also brand our cattle. Until Netz explained why we do it – to enjoy the pain

of “applying the iron until – and well after – the flesh of the animal literally

burns”, I had always thought that we brand our cattle because they cannot carry

notarized title deeds anymore than they can read off-limits signs. Incidentally,

I have never myself encountered a rancher who expensively indulges in the

sadistic pleasure of deeply burning the flesh of his own hoofed capital, opening

the way for deadly infection; the branding I know is a quick thrust of the hot

iron onto the skin, which is not penetrated at all, and no flesh burns.

We finally learn who is really behind all these perversities, when branding is

“usefully compared with the Indian correlate”: Euro-American men, of course, as

Professor Netz calls us. “Indians marked bison by tail-tying: that is, the tails

of killed bison were tied to make a claim to their carcass. Crucially, we see

that for the Indians, the bison became property only after its killing.”

We on the other hand commodify cattle “even while alive”. There you have it, and

Netz smoothly takes us to the inevitable next step:

“Once again a comparison is called for: we are reminded of the practice of

branding runaway slaves, as punishment and as a practical measure of making sure

that slaves – that particular kind of commodity – would not revert to their

natural free state. In short, in the late 1860s, as Texans finally desisted from

the branding of slaves, they applied themselves with ever greater enthusiasm to

the branding of cows.”

Texans? Why introduce Texans all of a sudden, instead of cowboys or

cattlemen? It seems that for Professor Netz in the epoch of Bush II, Texans are

an even more cruel sub-species of the sadistic race of Euro-American men (and it

is men, of course). As for the “enthusiasm”, branding too is hard work, and I

for one have yet to find the vaqueros who will do it for free, for the pleasure

of it.

By this point in the text some trivial errors occur, readily explained by a

brilliantly distinguished academic career that has understandably precluded much

personal experience in handling cattle. Professor Netz writes, for example, that

“moving cows over long distances is a fairly simple task. The mounted humans who

controlled the herds – frightening them all the way to Chicago . . .”. Actually,

it is exhausting work to lead cattle over any distance at all without causing

drastic weight loss – even for us in Bolivia when we walk our steer to the

market, in spite of far more abundant grass and water than Texas or even the

upper Midwest ever offered, at the rate of less than nine miles a day to cover a

mere 200 kilometres, instead of several times that distance to reach Chicago.

Used as we are to seeing our beautiful Nelor cattle grazing contentedly in a

slow ambling drift across the pastures, it is distressing to drive them even at

the calmest pace for the shortest distances; they are so obviously tense and

unhappy, and of course they lose weight with each unwanted step. As for

“frightening them all the way to Chicago”, that is sheer nonsense: nothing is

left of cattle stampeded a few days, let alone all the way to Chicago.

Unfortunately, his trivial error makes it impossible for Netz to understand the

difference between ranging and ranching that he thinks he is explaining.

All this and more besides (horses are

“surrounded by the tools of violence”) occurs in the first part of a book that

proceeds to examine at greater length the cruelty of barbed wire against humans.

He starts with the battlefield – another realm of experience that Netz cannot

stoop to comprehend. He writes that barbed wire outranks the machine gun in

stopping power, evidently not knowing that infantry can walk over any amount of

barbed wire if it is not over-watched by adequate covering fires, and need not

waste time cutting through the wires one by one. Nowadays well-equipped troops

have light-alloy runners for this, as other purposes, but in my day, our

sergeants trained us to cross rolls of barbed wire by simply stepping over the

backs of prone comrades, who were protected well enough from injury from the

barbs by the thick wool of their British battle dress – because the flexible

rolls gave way of course.

Perhaps because the material is rather directly derived from standard sources,

no such gross errors emerge in the still larger part of the book devoted to the

evils of the barbed wire of the prison camps, and worse, of Boer War British

South Africa, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (Guantanamo no doubt awaits a

second edition). It is reassuring if not exactly startling to read that

Professor Netz disapproves of prison camps, concentration camps and

extermination camps, that he is not an enthusiast of either the Soviet Union or

Nazi Germany, while being properly disapproving of all imperialisms of course.

But it does seem unfair to make barbed wire the protagonist of these stories as

opposed to the people who employed barbed wire along with even more

consequential artefacts such as guns. After all, atrocities as extensive as the

Warsaw Ghetto with its walled perimeter had no need of barbed wire, any more

than the various grim fortresses and islands in which so many were imprisoned,

tortured and killed without being fenced in.

There is no need to go on. Enough of the text has been quoted to identify the

highly successful procedures employed by Reviel Netz, which can easily be

imitated – and perhaps should be by as many authors as possible, to finally

explode the entire genre. First, take an artefact, anything at all. Avoid the

too obviously deplorable machine gun or atom bomb. Take something seemingly

innocuous, say shoelaces. Explore the inherent if studiously unacknowledged

ulterior purposes of that “grim” artefact within “the structures of power and

violence”. Shoelaces after all perfectly express the Euro-American urge to bind,

control, constrain and yes, painfully constrict. Compare and contrast the easy

comfort of the laceless moccasins of the Indian – so often massacred by booted

and tightly laced Euro-Americans, as one can usefully recall at this point.

Refer to the elegantly pointy and gracefully upturned silk shoes of the Orient,

which have no need of laces of course because they so naturally fit the human

foot – avoiding any trace of Orientalism, of course. It is all right to write in

a manner unfriendly or even openly contemptuous of entire populations as

Professor Netz does with his Texans at every turn (“ready to kill. . . they

fought for Texan slavery against Mexico”), but only if the opprobrium is always

aimed at you-know-who, and never at the pigmented. Clinch the argument by

evoking the joys of walking on the beach in bare and uncommodified feet, and

finally overcome any possible doubt by reminding the reader of the central role

of high-laced boots in sadistic imagery.

That finally unmasks shoelaces for what they really are – not primarily a way of

keeping shoes from falling off one’s feet, but instruments of pain, just like

the barbed wire that I have been buying all these years not to keep the cattle

in, as I imagined, but to torture it, as Professor Netz points out. The rest is

easy: the British could hardly have rounded up Boer wives and children without

shoelaces to keep their boots on, any more than the very ordinary men in various

Nazi uniforms could have done such extraordinary things so industriously, and

not even Stalin could have kept the Gulag going with guards in unlaced Indian

moccasins, or elegantly pointy, gracefully upturned, oriental shoes.

Le Monde diplomatique

Histoire politique du

barbelé

OLIVIER RAZAC

La

Fabrique-Editions, Paris, 2000, 111 pages, 59 F.

JANVIER 2001

|

Original, l'objet de ce

livre met en lumière une évolution majeure des société occidentales. Si

l'image du fil de fer barbelé reste associée à celle de l'oppression, de la

barbarie et de la mort, c'est que son histoire se confond avec trois grands

événements tragiques qui hantent notre modernité : l'extermination des

Indiens d'Amérique, la « boucherie » de la première guerre mondiale et le

génocide des juifs et des Tziganes durant la seconde.

Pourtant, inventé pour

protéger les propriétés des fermiers américains du passage des troupeaux...

et des Indiens, le barbelé est rapidement devenu un instrument privilégié de

pouvoir et de domination : par sa facilité d'utilisation et son faible coût

économique, il permet en effet d'organiser l'espace en un territoire

quadrillé et d'assurer le contrôle des populations et des corps qui

s'inscrivent dans ce territoire, hommes ou bêtes, de manière efficace et

durable. |

|

|

|

|

Bien qu'il soit encore

largement utilisé à travers le monde, le barbelé est progressivement supplanté

par des systèmes de protection et de surveillance de plus en plus sophistiqués,

comme les portails électroniques, les caméras vidéo en circuit fermé ou les

logiciels spécialisés dans la reconnaissance automatique des visages. Ces

nouvelles technologies de domination, plus efficaces et moins repérables,

attestent qu'« une nouvelle orientation se dessine maintenant qui consiste,

pour le pouvoir, à investir l'espace dans la plus grande discrétion ».

OLIVIER PIRONET

Critique de:

Olivier Razac,

Histoire politique du barbelé (la prairie, la tranchée, le camp),

La Fabrique, 2000, 111 p.

Le

barbelé, un outil au service du pouvoir

"Sous les pavés, la

plage." Et sous les barbelés? Le philosophe Olivier Razac répond à cette

question en fournissant un essai aussi court que salutaire. L'ambivalence du

barbelé, qui frise bientôt l'ambiguïté, consiste au fil des âges à passer de la

protection des biens à la surveillance disciplinaire des hommes. Outil

économique servant à délimiter l'espace, ce fil de fer que renforcent de

multiples "barbes" dissimule assez mal qu'il est avant tout le vecteur de l'

"inscription spatiale des relations de pouvoir". D'où l'intérêt dans ce texte de

dégager, par-delà "sa vocation agricole", un paradigme politique des multiples

usages possibles dudit outil: c'est ce que propose cette "histoire du barbelé" à

travers trois grandes catégories: la prairie américaine, la tranchée de la

Grande Guerre et le camp de concentration nazi.

De

son invention par Glidden en 1874 à son utilisation massive dans la délimitation

des frontières de l'Europe de 1999, le bon vieux barbelé ne dément pas son

succès mondial. Véritable "révolution dans l'exploitation de la prairie", il

contribue à l'expansion des fermiers américains davantage que le chemin de fer

ou les lois!

Olivier Razac

tempère toutefois l'optimisme de la conquête de l'Ouest en rappelant que cette

dernière s'accompagne de l'ethnocide des habitants de ces terres, les Indiens -

que les barbelés dans les prairies ne cesseront de repousser de plus en plus

loin. Barbelé versus nomadisme. Et l'auteur de régler son sort aux mythes du

rancher ou du cow-boy "avec sa panoplie de surhomme"! Mais "la corde du diable"

n'a pas fini de faire parler d'elle, aussi retrouve-t-on le barbelé devant

toutes les tranchées de la Grande Guerre, imparable moyen de ralentir la

progression de l'ennemi hors de ses lignes ou positions. Revus et corrigés,

quasiment "increvables" (ne résistent-ils pas même aux bombardements?), les

barbelés se conjuguent désormais en "ronces artificielles" et autres "toile[s]

d'araignée[s]" retenant dans des postures ridicules les hommes tombés au combat:

ainsi s'exprime selon Razac l'absurdité du conflit où triomphe la bestialité de

l'homme…

Le

camp de concentration et "la frontière brûlante"

Mais "symbole", le

barbelé ne le devient vraiment qu'avec l'apparition du camp d'extermination nazi

où il se signale comme un "élément central de la gestion totalitaire de

l'espace". Clôturant tous les lieux, rendant obsolète la distinction classique

entre un intérieur et un extérieur clairement assignables, ce que Robert Antelme

nomme "la frontière brûlante" dans L'espèce humaine s'affirme en effet comme

"métaphore de la violence politique". C'est que les barbelés ne divisent pas

seulement l'espace mais raturent aussi la liberté des êtres.

Les

camps de la mort ne manqueront pas d'ailleurs de décliner cet outil sous toutes

les formes de l'horreur, à l'enseigne de la "roseraie", cette cage de barbelés

où l'on enferme les prisonniers pendant de longues heures, ou du "chemin du

ciel" désignant l'étroit chemin d'accès, protégé par branchages et barbelés,

menant aux chambres à gaz. Derrière ces trois paradigmes pointant la

signification politique du barbelé, il convient donc de dégager le primat de la

clôture - de quelque matériau qu'elle soit - dont se sert constamment la

civilisation pour concrétiser les "distinctions sociales" dont elle s'alimente.

La dernière partie de l'histoire du barbelé conceptualise en ce sens la notion

de "frontière" à partir d'un processus d'exclusion/inclusion éclairant. Car le

croisement entre technologie et pouvoir n'accouche du barbelé (il faut dire

également, avec l'auteur: du portail électronique, du vigile d'accueil, des

caméras de surveillance, des zones de résidence protégées, des parcs de loisirs

hautement sécurisés) que pour valoriser l'espace ainsi circonscrit comme

producteur de valeur à l'encontre d'une extériorité source de douleur et de

vacuité. Pour le dire autrement, dans l'intention de réifier une opposition

entre la vie et la mort.

Clôture interactive et surveillance

En dégageant

l'importance accrue à notre époque des discrètes "interfaces d'accès" qui

dépassent de loin les antagonismes tangibles du "seuil" et de la "frontière »,

Olivier Razac nous alerte sur le "passage du physique de la clôture à l'optique

de la surveillance" qui s'opère de nos jours. "La clôture et la porte

représentaient une séparation binaire: c'était soit ouvert, soit fermé. Le

barbelé, par sa connexion nécessaire avec une surveillance, a représenté un

affinement des techniques de filtrage, une clôture interactive, dont la réaction

s'adapte à l'événement grâce à l'information fournie par la surveillance. Les

nouvelles technologies optico-électroniques vont plus loin dans ce sens, en

permettant de délimiter un lieu sans barrer l'espace."

Un

espace biopolitique tenant lieu de "hiérachisation sociale" et faisant la chasse

à tous ceux qui ne rentrent pas dans le rang, dans le camp, devenu le lieu par

excellence de l'ostracisme. On regrette que l'auteur ne développe pas ici la

distinction essentielle entre borne et frontière telle qu'elle s'établit sous la

plume du Kant de la Critique de la raison pure ou de Bayle dans l'article

"Rorarius" de son Dictionnaire. Mais si ce qu'on franchit ne se réduit pas à ce

qu'on dépasse, on peut souligner ce que Hegel indique avec un rien d'ironie au §

LX de son Encylopédie: "On ne connaît, on ne sent une marque ou une limite que

lorsqu'on va au-delà de cette limite." Or l'Histoire du barbelé est un aussi

incontestable qu'efficace pied de nez aux biopouvoirs.

L'heure est donc au cloisonnement, au repli frileux dans son home sweet home?

Qu'à cela ne tienne, profitons-en pour lire et relire l'essai percutant

d’Olivier Razac! Sous les barbelés, la page…

Frédéric Grolleau

|

|

|

Oda al alambre de púa

PABLO NERUDA

(Nuevas

odas elementales)

En mi país

alambre, alambre...

Tú recorres

el largo

hilo de Chile,

pájaros,

soledades,

y a lo largo,

a lo ancho,

extensiones baldías,

alambre,

alambre...

En otros sitios

del planeta

los

cereales

desbordan,

trémulas olas

hace el viento

sobre el trigo.

En otras

tierras

muge

nutricia y poderosa

en las praderas

la ganadería;

aquí,

montes desiertos,

latitudes,

|

no hay hombres,

no hay caballos,

sòlo cercados,

púas,

y la tierra

vacía.

En otras partes

cunden

los repollos,

los quesos,

se multiplica

el pan,

el humo

asoma

su penacho

en los techos

como el tocado

de la codorniz,

aldeas

que ocultan,

como la gallina

sus huevos,

un nido de tractores:

la esperanza.

Aquí

tierras

y tierras,

tierras enmudecidas,

tierras ciegas,

tierras sin corazón,

tierras sin surco.

En otras partes

pan,

arroz, manzanas...

En Chile alambre, alambre...

|

|

Olivier Razac, Storia politica del

filo spinato, Edizioni Ombre Corte, 2001, p. 94

Senza dubbio curiosa

l’idea di scrivere una storia politica del filo spinato, un “oggetto” certo

inconsueto per il senso comune. Ma non è priva di fondamento l’idea che il filo

spinato sia uno degli oggetti-simbolo del mondo contemporaneo: come è possibile

non associare l’idea del filo spinato all’immagine dei lager nazisti, purtroppo

uno dei luoghi-simbolo del Novecento? Ed i lager erano delimitati proprio dal

filo spinato, che stabiliva i confini di quel mondo di oppressione, tirannia e

violenza.

Ma se una persona della seconda metà del Novecento associa

probabilmente il filo spinato ed i lager, i soldati reduci dalla prima guerra

mondiale è probabile che associno l’idea del filo spinato alle immagini delle

trincee, al fuoco delle mitragliatrici, agli assalti alle postazioni nemiche,

assalti che spesso venivano ostacolati o fermati proprio dal filo spinato.

Il libro di Razac racconta proprio l’utilizzo del filo

spinato in questi due momenti topici della storia del Novecento, oltre che

raccontare la prima utilizzazione del filo spinato, negli Stati Uniti

nell’Ottocento, quando venne inventato per evitare che le mandrie pascolassero

liberamente nei campi, ed anche per allontanare gli indiani.

L’inventore del filo spinato è un certo J. F. Glidden, che

nel 1874 deposita il brevetto di “due fili di ferro e di una serie di spine,

fatte con pezzi di filo di ferro e di una serie di spine, fatte con pezzi di

filo di ferro ritorto e tagliato obliquamente alle due estremità”.

L’invenzione del filo spinato comportò un deciso cambiamento

nella lotta tra grandi allevatori e piccoli agricoltori. Intorno alla metà del

secolo scorso le grandi praterie americane erano dominate da mandrie di bovini

che vi pascolavano liberamente. Con la progressiva colonizzazione e la messa a

coltura del suolo, gli agricoltori avevano la necessità di impedire l’accesso

dei loro campi alle mandrie. Il filo spinato si rivelò per questo fine un

utilissimo strumento, per la sua economicità, la sua leggerezza e la sua

facilità d’uso.

Momenti fondamentali della colonizzazione del west furono l’Homestead

Act del 1862 e il Dawes Act del 1887; il primo assegnava 80 acri di

terra libera ad ogni famiglia di agricoltori che la coltivasse, il secondo

permetteva di assegnare non più solo le terre libere, ma anche le terre indiane,

che si trovano così ad essere lottizzate e recintate.

Il momento successivo della storia politica del filo spinato

è la prima guerra mondiale, anche se l’utilizzo del filo spinato in battaglia

inizia però nel 1870, con la guerra franco-prussiana (allora però si trattava

ancora di un semplice filo di ferro liscio).

Le strategie militari tra la fine dell’Ottocento e l’inizio

del Novecento prevedevano l’offensiva di grandi masse di soldati, con una

notevole mobilità ed una grande capacità di sfondamento. Queste strategie si

infransero sulle trincee, sui campi minati e sulle barriere di filo spinato, che

ancora una volta si dimostrò uno strumento dissuasivo semplice, economico e di

facile utilizzazione.

Il predominio della guerra di trincea durò fino agli ultimi

mesi della prima guerra mondiale, quando l’evoluzione tecnologica dei carri

armati fornì gli eserciti dei mezzi tecnici per superare le barriere difensiva

avversarie.

Infine, il libro racconta l’utilizzo del filo spinato nei

lager nazisti. La struttura dei campi nazisti, fossero essi di concentramento o

di sterminio, era sempre la medesima: alcune fila di baracche racchiuse da filo

spinato, attraverso il quale passava corrente elettrica, ed alcune torrette di

controllo che sorvegliavano la recinzione con l’ausilio di potenti fari e

mitragliatrici.

Secondo Razac, “si può sostenere che l’elemento centrale

della costruzione di un campo è, paradossalmente, il recinto di filo spinato”,

che diventa “l’elemento essenziale di una gestione totalitaria dello spazio”. Il

filo spinato delimita due mondi, il mondo esterno ed il regime

concentrazionario”. Come ha scritto primo Levi, quando il lager di Auschwitz fu

liberato, “la breccia nel filo spinato dava l’immagine concreta [della

libertà]”.

Fabrizio Billi

CULTURA Domenica

13

Maggio 2001

Le trasformazioni di un oggetto che ha segnato

l’organizzazione dello spazio

Filo

spinato, c’è ma non si vede

Marco Belpoliti

L’INVENTORE del filo spinato è un colono americano dell'Illinois, J.-F. Glidden.

Il brevetto è stato depositato nel 1874: due fili, di cui il secondo

attorcigliato attorno al primo e alle spine di filo di ferro ritorto e tagliato

obliquamente alle due estremità. Una piccola ma grande invenzione che permette

di cintare enormi porzioni di terra nel West e sostituisce a modico prezzo la

penuria di legno e pietra, materiali tradizionali per circoscrivere gli

appezzamenti di terreno. La sua efficacia è superiore a quella del filo nudo,

che tende ad allentarsi a causa del calore, e non contiene le micidiali spine.

Il filo inventato da Glidden disciplina la migrazione delle mandrie di bestiame

attraverso i territori del West e assesta un duro colpo all'impero del bestiame.

La prima fabbrica ne inizia la produzione nel 1874, e dalle 270 tonnellate del

1875, nel 1901 si è già intorno alle 135.000. Glidden ha brevettato anche una

macchina che lo produce in serie e a basso costo. Se il mito del Far West è

associato al nomadismo, allo spazio aperto e all'egualitarismo - tre miti

fondatori della civiltà americana -, il filo spinato ne ha fatto franare la

dimensione epica e nel contempo ha contribuito a distruggere l'organizzazione

sociale dei nativi indiani, incentrata su un uso comune e aperto del territorio

di caccia. Oliver Razac traccia in Storia politica del filo spinato (Ombre

Corte, Verona, pp. 93, lire 15.000), la vicenda di questo “oggetto” che con la

sua presenza segna alcuni mutamenti nell'organizzazione dello spazio durante

l'ultimo secolo e mezzo. L'utilizzo del filo di ferro come difesa accessoria ha

inizio nel 1870, durante la guerra che oppone francesi e prussiani. Via via che

si entra nel XX secolo, dalla guerra russo-giapponese del 1904 alla Grande

guerra, il filo di ferro disposto a rete si rivela come la miglior difesa delle

postazioni militari. In tutti i ricordi dei combattenti, la trincea e il rovo

artificiale diventano immagini indelebili del conflitto. Spesse oltre trenta

metri, fissate a terra con picchetti di un metro e mezzo di altezza, confitti a

intervalli regolari, le reti di filo spinato, riavvolto in forme circolari,

diventano l'incubo di chi attacca: acciambellati dentro le buche scavate dalle

granate, i soldati attendono che i guastatori del genio, muniti di scudo, senza

fucile e con enormi cesoie in mano, taglino i fili di ferro. Nonostante queste

immagini ricorrenti, mescolate a quelle di alberi carbonizzati, crateri vuoti e

villaggi rasi al suolo, il filo spinato non diventa il simbolo della Prima

guerra mondiale.

Il

libro di Razac riporta in primo piano una delle questioni centrali della società

contemporanea: quella dell'uso disciplinare dello spazio. L'uso del filo spinato

ha il suo culmine nel campo di concentramento di Auschwitz.

L'architettura del Lager si fonda sul recinto e le torrette di controllo:

circoscrive uno spazio, non attraverso muri, come in un carcere o una prigione,

ma utilizzando la “trasparenza” e la transitorietà. Il campo sorge in modo

rapido ed economico grazie al filo spinato, dentro cui passa la corrente

elettrica, e che funziona come un dispositivo di esclusione e inclusione:

stabilisce il dentro e il fuori. Nella memoria collettiva della seconda metà del

XX secolo il filo spinato è diventato l'emblema della deportazione, della

barbarie e del genocidio. Ma coi suoi aculei di ferro è anche il simbolo del

passaggio da una forma di dislocazione a un'altra: dallo spazio circoscritto

mediante una barriera fisica, a quello in cui la barriera diventa invece

invisibile. Con le videocamere, i sensori elettronici, i satelliti-spia, il

controllo del territorio si fa discreto, scrive Razac, così che il filo spinato,

la rete che circonda gli Stati e separa i confini, tende a diventare virtuale:

dal materiale all'immateriale.

Le

nuove tecnologie ottiche permettono di delimitare i luoghi, filtrare i

frequentatori abituali, selezionare gli estranei senza sbarrare lo spazio o

delimitarlo. Il Check-point è il dispositivo che sostituisce, almeno in Europa e

negli Usa, il reticolo e la siepe metallica. Si transita attraverso soglie

invisibili, metal detector e visori che scrutano dentro gli oggetti e le

persone: dall'ottica passiva all'ottica attiva, come la definisce Paul Virilio.

La parola chiave della modernità diventa interfaccia, che indica non solo la

superficie di contatto tra due zone, ma anche la loro reciproca procedura di

scambio. Il filo spinato fa ormai parte della tecnologia pesante, arcaica, un

simbolo imbarazzante di oppressione.

Piero S. Graglia

Dottore di ricerca in storia del federalismo e dell'integrazione europea