10-12-2002

Caroline Blackwood

(1931-1996)

Commentary

Gabrielle Annan, reviewing Nancy

Schoenberger, Dangerous Muse: A Life of Caroline Blackwood (2001),

226pp., in Times Literary Supplement (6 July 2001), p.25, gives details:

|

Lady Caroline Blackwood; b. 1931, dg. and eldest child of Marquess of Dufferin

and Ava and Maureen née Guinness; raised at Clandeboye; terrorised by nanny; m.

Lucian Freud, Israel Citkowitz, with whom three dgs. (poss. one by Ivan Moffat),

and Robert Lowell ,with whom a son; shared with him her house on Redcliffe Sq.,

London, and a country house in Kent while he ‘commuted grumpily to Essex

University where the students wanted him to analyse the best lyrics of Bob Dylan

and the Beatles’ (Annan); ‘what made her mesmeric was not just her beauty, but

her wit, funniness, and her tragic, nihilistic insight which went like a dagger

into character and motive. Her writing is often hilarious, and always black.’;

d. cancer. Remarks that Schoenberger’s ‘own input is not distinguished enough

for her subject.; quotes Lorna Sage (Bad Blood): ‘Caroline hired a succession of

more-or-less disastrous people ranging from superannuated hippies to drunken

professional butler-and-housekeeper double acts to do the cooking, housework, &c.;

in London she ate out or picknicked [...] and ocasionally got contract cleaners

in. |

|

|

|

She lived for the most part in grand squalor [ … but] the conversation was

marvellous and went on well into the night.’; quotes Robert Lowell: ‘I’m manic

and Caroline’s panic. We’re like two eggs cracking.’ Lowell died in a taxi on

his way to Hardwick’s house on leaving Caroline; attachment to Andrew Harvey,

Oxford don; speaks of the ‘macabre factoid fairy tale The Last of the Duchess in

which she tries but fails ton interview the dying Duchess of Windsor.’

BIBLIOGRAPHY

For All That I Found There.

London: Duckworth, 1973; New York: Braziller, 1974.

The Stepdaughter.

London: Duckworth, 1976; New York: Scribner, 1977.

Great Granny Webster.

London: Duckworth, 1977;

New York: Scribner, 1977.

Darling, You Shouldn't Have

Gone to So Much Trouble, by Blackwood and Anna Haycraft, with drawings by Zé.

London:

Cape,

1980.

The Fate of Mary Rose.

London: Cape,

1981; New York: Summit, 1981.

Goodnight Sweet Ladies.

London: Heinemann, 1983.

Corrigan.

London: Heinemann, 1984; New York: Viking, 1985.

On the Perimeter.

London: Heinemann, 1984; New York: Penguin, 1985.

In the Pink: Caroline

Blackwood on Hunting.

London:

Bloomsbury,

1987.

The Last of the Duchess.

London: Macmillan, 1995; New York: Pantheon, 1995.

April 02, 1995

Titled Bohemian; Caroline

Blackwood

By Michael Kimmelman

Read this article

here

Aug. 22, 2001, 3:22PM

A full and empty life

Author probes Lady Caroline

Blackwood's years and loves

By EMILY

FOX GORDON

DANGEROUS MUSE:

The Life of Lady Caroline Blackwood.

By Nancy Schoenberger.

Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, $27.50.

|

CAROLINE Blackwood had, as her

third husband Robert Lowell called it, and as the photographs in Dangerous

Muse attest, an extraordinary "ragged beauty." In her youth she was graceful

and slender, with an elegantly astringent gaze. In middle age she was gaunt and

riveting, her enormous eyes dramatically lined with black. She also looked

unwashed, which she often was.

The photographs are an

important element in Nancy Schoenberger's biography, because Blackwood's beauty

was her chief distinction. In her later years she produced nine novels and books

of literary journalism, but Blackwood is remembered much better for her

connections with famous men than for her own accomplishments. Lowell, the most

celebrated of her three husbands, was clutching a portrait of Caroline painted

by her first husband, the artist Lucian Freud, when he died of a heart attack in

a New York cab.

The Anglo-Irish genealogy of

Lady Caroline, who was born in 1931, was complex enough to make the reader long

for a tree diagram. Her father, who died when she was 13, was Basil "Ava"

Blackwood, the fourth Marquess of Dufferin and Ava. Her mother was Maureen

Guinness, one of three famously beautiful sisters and a woman of stunning

fatuousness.

|

|

|

|

Among Caroline's ancestors on

the Blackwood side were the Irish playwright Richard Sheridan (The School for

Scandal) and a loony grandmother who dressed in a fairy costume and flitted

barefoot through the halls of Clandeboye, the gloomy and neglected ancestral

Blackwood mansion, startling visitors.

Blackwood's childhood was so

gothically dysfunctional that Schoenberger's straightforward account of it

trembles on the edge of parody. The parents played bridge and drank. The

children were abandoned to the care of negligent and sadistic nannies, one of

whom actually stole the children's food, leaving them half-starved. Given their

background, it seems almost tiresomely overdetermined that Caroline and her

brother Sheridan would become alcoholics. What is surprising is that the third

sibling, Perdita, did not.

There was a fearful symmetry in

Caroline's marriages: Each husband represented one of the arts -- painting,

music and poetry. Lucian Freud (grandson of Sigmund, of whom Caroline's mother

had never heard) was a social-climbing bohemian dandy when he met the

18-year-old Caroline. He found her aristocratic lineage irresistible, and she

enjoyed the commotion she caused in her mother's horsey social circle by

marrying a Jew. ("You know that poor Maureen's daughter made a runaway match

with a terrible Yid?" Evelyn Waugh wrote in a letter to Nancy Mitford.)

The marriage burned itself out

after three years, by which time Caroline's drinking habit had firmly

established itself.

Next, after a Hollywood

interval, came the musician. Israel Citzkowitz was a composer of great promise

who ended up as a rather pathetic caretaker figure. He fathered three of

Caroline's four children (or so he thought: One was probably the product of

Blackwood's earlier involvement with screenwriter Ivan Moffat).

While Caroline drank and smoked

(through four pregnancies!) and wrote, he watched over the children, tagging

along after Caroline in order to stay close to them. At one point, after the

marriage dissolved, he occupied the second floor of a three-story townhouse in

London while Caroline and Lowell lived above him on the third floor, and the

children -- with a retinue of nannies -- lived on the first.

"Two eggs cracking" was

Lowell's characterization of himself and Blackwood. Caroline had hitherto been

rather passive in her relations with men, but she actively campaigned to take

Lowell away from his wife, Elizabeth Hardwick (a far more important figure in

the American intellectual world than Blackwood would ever prove to be).

Independent and supportive,

Hardwick had seen Lowell through recurrent manic episodes and the promiscuous

entanglements with women that accompanied them. Blackwood offered to "share" his

psychotic breaks, to become one with him in his suffering, but in fact she

tended to run away when he was at his worst.

The two lived in what an

observer called "grand squalor" in the country house that Caroline bought for

them. (The reader is continually reminded that it takes a lot of money to float

a life lived according to impulse.) They wrote, gave house parties, drank. The

children -- a fourth was born during this period -- were consigned, as their

mother had been, to the care of negligent nannies. One daughter was severely

burned in an accident and spent three months in a hospital. Another, Natalya,

was simply forgotten and left alone in a London apartment while Blackwood and

Lowell were traveling. Two years later, at age 17, she died of a heroin

overdose.

Blackwood served Lowell as an

alternately beguiling and threatening erotic muse -- the "dolphin" of his poems

-- while Hardwick beckoned him back toward security. His poetry became a

chronicle of his whipsawed emotions. Eventually he found Blackwood more

frightening than arousing and began to see his former marriage as a home from

which he had exiled himself. Traveling from London to New York to rejoin

Hardwick, he died.

After Lowell, Blackwood

continued to drink, but she plunged into writing with surprising discipline.

Schoenberger plods through Caroline's oeuvre, diligently pointing out

correspondences between life and art. If the effort seems a little perfunctory,

it is probably because Schoenberger senses that having been fed a diet of

scandal and outrage throughout the book, her readers will be in no mood for

literary exegesis.

After a last love affair with a

much younger gay man, Caroline dwindled. The last photograph in the book shows

her on the grounds of her Sag Harbor, N.Y., estate, a look of muzzy hauteur on

her ravaged face. Schoenberger never met her subject. On the day the two were to

be introduced, Lady Caroline was hospitalized for cancer. She died soon after,

on Feb. 14, 1996. She was 64.

The biography Schoenberger

produced seems to suffer from the same near-miss problem; the reader never feels

that she has quite met Blackwood either. Schoenberger has assembled an

impressive pastiche of quotes and views: It seems everyone had something to say

about Blackwood's beauty, her drinking style, her black wit, her poor hygiene

("She needs a damn good scrub all over," said Ian Fleming), the arrogant,

aristocratic carelessness she betrayed by leaving empty liquor bottles,

cigarette butts and used sanitary napkins strewn on the floors of hotel rooms.

But Caroline herself remains

elusive. Perhaps the problem is inherent in a biography of a recently deceased

subject; the impression Blackwood left on the friends, family members and lovers

who served as Schoenberger's informants may not have come into full focus by the

time she interviewed them.

Over and over, the reader is

amazed by Blackwood's behavior, but in the absence of insight, amazement turns

to puzzlement to something like irritation. Caroline had all the standard

accoutrements of celebrity -- beauty, wealth, position, a commanding presence.

In addition, she had wit and literary flair. But she seems to have lacked an

internal life (to say nothing of a moral compass). Perhaps she had one but

drowned it in drink.

In the end, I can't decide

whether the hole at the center of Schoenberger's life of Caroline Blackwood is

the fault of the biographer or simply a faithful representation of the emptiness

of her subject.

Emily Fox Gordon is the

author of Mockingbird Years: A Life In and Out of Therapy. She lives in

Houston.

July 8, 2001, Sunday

The Uses of Enchantment

By Hilary Spurling

DANGEROUS MUSE

The Life of Lady Caroline Blackwood.

By Nancy Schoenberger.

Illustrated. 377 pp. New York:

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday. $27.50.

It is common enough for

biographers to feel haunted by their subjects, and commoner still for potential

subjects to go to considerable lengths to thwart unwanted attempts to write

their lives. But I have never before come across a biographer who suggests, as

Nancy Schoenberger does, that her subject tried to silence her by arranging a

car crash from beyond the grave.

Admittedly, contemporaries

often saw Caroline Blackwood as some sort of sorceress. Her father, the fourth

Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, was a changeling, according to his mother, who

believed that fairies had stolen her real child at birth. Lord Dufferin grew up

to marry Maureen Guinness, one of the three Golden Guinness Girls, each heir to

a brewing fortune. ''The sisters are all witches,'' wrote John Huston, who

stayed with one of them in Ireland on his way to shoot ''The African Queen,''

''lovely ones to be sure, but witches nonetheless.'' They had pale gold hair,

pale blue eyes and transparent skin. Huston believed they could change men into

swine, and back again, without anybody realizing.

This was a gift Lady Caroline

inherited from her mother. She captivated people to her dying day. Her three

husbands, all artists, felt themselves first magically transformed, then

threatened with extinction in her vicinity. She was 22 in 1953, when she married

the painter Lucian Freud, a saturnine youth said to stalk the London streets in

those days wearing a greatcoat belonging to his grandfather Sigmund and with a

hawk tethered to his wrist. Caroline claimed it was only after she left him that

Freud's nudes took on the corpselike, charnel-house allure that became his

trademark. She married next Israel Citkowitz -- billed as a great composer,

Aaron Copland's chosen heir -- and dumped him when he failed to measure up as an

American Beethoven. Her third husband was Robert Lowell, who portrayed her, in

''The Dolphin,'' as a miraculous creature, part fish, part mermaid, spouting a

joyful liberating spume that batters its victims and knocks the breath out of

them in the end.

All three husbands were

bewitched, in the sense of being erotically obsessed and financially dependent.

Lady Caroline possessed at birth every gift the fairies could bestow, starting

with fabulous wealth, dazzling beauty and an ancient pedigree. Her

great-grandfather had been viceroy of India. She was directly descended from the

playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and indirectly from King Charles II of

England. Princess Diana was a distant cousin, but, unlike the luckless princess,

Caroline had brains and literary talent in her own right. All that was missing

was a human heart.

It seems to have been withered,

or scorched, out of her, in childhood. She was the eldest of three siblings more

or less abandoned by their parents to be brought up, according to upper-class

English custom, by servants at Clandeboye, the family's rambling great house in

Northern Ireland. Ghosts, and worse, stalked her earliest memories. Caroline

said that her grandmother (the one who believed in fairies) had tried to smash

her baby brother's head against a stone at his christening. The children grew up

terrified of the dark, of strange knockings at night, of being sent alone to

visit their great-grandmother, who lived in a dark, creaky house with a one-eyed

maid and a one-legged butler. Worst of all they dreaded their own nanny, who

alternately bullied, beat and starved them into submission.

Caroline and her sister

belonged to an aristocratic generation of girls destined solely for marriage,

preferably, in their case, to dukes' sons. Her response was to run away with a

penniless Jewish artist who spoke with the wrong accent, wore the wrong clothes

and came from a family no one knew anything about (Caroline and her mother were

still quarreling years later as to whether or not the marchioness had ever

actually heard of Sigmund Freud). Lucian Freud drank, gambled and hung out with

gangsters. A friend once threw himself out of Lucian's car sooner than continue

a journey with the painter at the wheel. ''Exactly,'' Caroline said with

satisfaction. ''That's what being married to him was like.''

She prided herself on trading

the power and privilege of her birthright for bohemian freedom. Caroline and her

mother had another of their running quarrels about the Guinness millions, and

how much of them the marchioness made over to her children. Caroline certainly

had enough to pay hotel bills for a year's honeymoon in Paris and, when the

couple moved to London, to buy a Georgian town house, a second house in the

country and a horse for Lucian to ride on weekends. But if their poverty was

relative, the squalor was genuine. People who cared about their homes learned to

cover up the furniture and put the ornaments away if Caroline was coming.

Washing was never her strong point. ''She needs a damned good scrub all over,''

said James Bond's creator, Ian Fleming, who liked his girls sleeker and squeaky

clean.

By the end of her life Lady

Caroline could wreck any room without effort at record speed. Chambermaids

recoiled. Hosts thought they had been burgled. Top hoteliers put her on a secret

blacklist. A young academic, who interviewed Lowell with Caroline in the 1970's,

described their New York hotel room awash with crumpled underwear, scattered

ash, empty vodka bottles, broken glass and bloody towels. Lowell left her

shortly afterward in self-defense. ''I'm manic,'' he said, explaining why they

had got on so well to start with, ''and Caroline's panic.''

The casualties were her

children. She had three Citkowitz daughters (though the parentage of the last

remains unclear) and a son by Lowell. Their upbringing was a replay of her own,

without the stability of Clandeboye. She treated them like baggage: troublesome

encumbrances constantly needing to be packed and unpacked, trundled from one

continent to another and dumped in the latest house or hotel room in the charge

of inadequate hired help. They grew up with mostly absent fathers and a mother

who drank herself insensible every night. Once she threatened to teach Lowell a

lesson by putting the children in the back of her car and ramming it into a

wall. ''I can see those children's faces, I can hear their voices crying on the

telephone to me,'' said a friend who watched helplessly as the eldest daughter,

Natalya, slid toward heroin addiction and early death. ''It was cruel. I think

all her children felt rejected by her. Natalya felt it most. She happened upon

the solution.''

Caroline's friends insist on

her uncompromising honesty, and it is true that the autobiographical stories and

novels she wrote -- mostly after Lowell's and Natalya's deaths -- make grim

reading. They are cool, clear, sharp, even scintillating, but preternaturally

cold. This is life itself vacuum-packed, so to speak, with the air sucked out of

it. She wrote a cookbook with a friend, ''Darling, You Shouldn't Have Gone to So

Much Trouble,'' full of dishes concocted at top speed, on surrealist principles,

from a reckless spillage of cans, packets and dehydrated powders, moistened

liberally with alcohol. The message couldn't have been clearer. The cook must

stay cool at all costs. ''Dishes that require her presence in the kitchen --

that require her loving surveillance in case they burn, curdle, shrink or

shrivel, or go wrong in some other unspeakable way, we cannot recommend.''

It was the principle on which

Caroline lived her life, and not only in the kitchen. The carefree insouciance

that captivated her friends was designed precisely to disguise the truth that

she didn't at bottom care much for anything or anyone, including, if not

especially, herself. Anita Brookner reviewed the cookbook with magisterial

rebuke: ''This is corrupt food, food intended to impress, to deceive, even

intended to inspire fear and loathing.''

Brookner might have been

describing the effect Caroline produced on those closest to her when the demons

that had surrounded her from birth finally closed in. Steven Aronson, who wrote

the 1993 Town & Country profile that inspired this gripping but underresearched

and overhasty book, said that toward the end he couldn't bear to look at her for

long. ''I'd get gooseflesh sometimes, because she was so haunted.''

''Dangerous Muse'' is not so

much a literary biography as a fable for our own times -- dramatic, chilling and

suggestive -- in the same way as Grimm's fairy tales (or for that matter Freud's

case histories) were for theirs.

Hilary Spurling's most

recent books are ''The Unknown Matisse'' and ''La Grande Thérèse.''

Saturday, August 4, 2001

DETNEWS

Dangerous Muse: The Life of

Lady Caroline Blackwood

By Nancy Schoenberger

Doubleday, $27.50

400 pages

'Muse' details sad life of Caroline Blackwood

By Brenda Maddox /

Washington Post Book World Review Service

Beauty is a dubious blessing, "muse" a doubtful

compliment. Both imply passivity: The action belongs to others, usually male.

Lady Caroline Blackwood's Irish-countryhouse beauty was the kind idealized by

W.B. Yeats -- "not natural in an age like this": large staring eyes, sculpted

cheekbones and haughty carriage suggesting ancestral portraits in the great

hall.

For Blackwood (1931-1996), a title and beauty (plus a Guinness fortune)

attracted three artists as husbands. Before, during and after chaotic marriages

to the Berlin-born British painter Lucien Freud, the Russian-Jewish American

composer Israel Citkowitz and the Boston-Brahmin poet Robert Lowell, she had

many lovers, drawn by the astonishing blue-green eyes and the aristocratic hint

of the beast in bed.

Does such seductiveness constitute inspiration? Nancy Schoenberger, a poet

and editor, acknowledges that muses are passive and therefore passe. The force

of her well-researched biography comes from Blackwood's discovery, at the age of

42, that she was a writer and a good one.

For this awakening, she needed muses of her own. First, there was the

long-suffering second husband, Citkowitz, who gave up composing to look after

their three daughters while she smoked, drank and wrote. Then there was the poet

Stephen Spender, who commissioned her to write for the British political and

literary journal Encounter.

Schoenberger, in her first solo biography, has tackled the biographer's

hardest task: writing the life of a disagreeable person, in this case, an

alcoholic and irresponsible mother with a pitiless world view.

Shoenberger is strong on both the social history of the transatlantic

literary and cafe society of 1950s and 1960, and on literary interpretation of

Blackwood's work. At the same time, however, her narrative is clogged by too

many famous names knocking back too many cocktails in flashy places. All in all,

it is a depressing story. Next time, Schoenberger should apply her skills to a

life of a more inspiring person.

NEW YORK TIMES OBITUARY

February,15, 1996

Lady Caroline Blackwood, Wry

Novelist, Is Dead at 64

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

Lady Caroline Blackwood, a writer of wry, macabre novels and essays, and a

beguiling Anglo-Irish aristocrat who married the painter Lucian Freud and the

poet Robert Lowell, died yesterday in the Mayfair Hotel in Manhattan, where she

stayed the last few weeks while she was ill. She was 64.

The cause was cancer, said her

daughter Ivana Lowell.

She published nine books and

was best known and much admired in Britain. Among her works was "The

Stepdaughter," a short epistolary novel about an abusive woman abandoned by her

husband and left with his hideous daughter. Another novel, "The Fate of Mary

Rose," was about an increasingly deranged mother's fatal obsession with her

daughter's safety.

Her most recent book, "The Last

of the Duchess," was an eccentric, Kafkaesque account of her vain attempt to

visit the ailing Duchess of Windsor. It revolved mostly around the Duchess's

powerful lawyer, Suzanne Blum, portrayed in the book as obsessed with her client

to the point of erotic fantasy.

British critics noted the

"brilliant irony" and "rather brilliant bitchiness" of her writing, comparing it

with the work of Muriel Spark and Iris Murdoch, among others. In her prose and

in person, she exhibited a razor-sharp wit and offbeat sensibility. A dramatic

woman, delicately built, intense and vulnerable, she was a famous beauty in her

youth, and in later years remained striking for her extraordinary eyes, which

Mr. Freud made into giant spheres in his hypnotic portraits.

One portrait played a curious

role in her life, as she related in an interview last year. During the 1950's,

when she and Mr. Freud were living in Paris, "Lucian got a call out of nowhere

from a mistress of Picasso's who asked him if he could come round and paint

her," she said. "The woman wanted to make Picasso jealous. Lucian very politely

said maybe he could paint her portrait later, but not now because he happened to

be in the midst of doing his wife's portrait."

That picture, she said, was

"Girl in Bed," a work that years later also figured in the death of Robert

Lowell, her third husband. Their marriage was in tatters when, the story goes,

Lowell left her in Ireland and flew to New York City. When his taxi arrived at

his apartment on West 67th Street, the driver found Lowell slumped over. A

doorman summoned Elizabeth Hardwick, the writer and editor, whom Lowell had left

to marry Lady Caroline; she happened to live in the same apartment house. Ms.

Hardwick opened the taxi door to be confronted with her former husband's corpse.

He was clutching "Girl in Bed."

Lady Caroli'e moved amo'g

several worlds: from the insular Anglo-Irish upper classes, which she largely

rejected for the smart set of postwar England and then for the liberal

intelligentsia of New York City in the 1960's and 70's. During much of the last

35 years, she lived in the United States, splitting her time in recent years

between an apartment in Manhattan and a house in Sag Harbor, L.I., that once

belonged to President Chester A. Arthur.

Lady Caroline Hamilton Temple

Blackwood was born in London on July 16, 1931. She was descended on her father's

side from the great 18th-century dramatist Richard Brinsley Sheridan and was a

Guinness on her mother's side. (She liked to joke that she found stout

undrinkable.) She grew up in the ancestral stone mansion, Clandeboye, in County

Down in Northern Ireland.

Her great-grandfather, Lord

Dufferin, was an eminent Victorian rumored to have been Disraeli's illegitimate

son. Queen Victoria made him Viceroy of India, where he used to sit on his

throne, fanned by peacock feathers. "Kipling loved my great-grandfather and

wrote lots of very bad poems to him," Lady Caroline said. "He had a fatal effect

on poets."

Her mother, Maureen, the

Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, is a flamboyant figure in London who, according

to one newspaper account, gave a black eye to Sir Oswald Mosley, the English

Fascist, after he made a pass at her in Antibes. Her father, Basil, the Marquess,

was a friend of Evelyn Waugh and part of the circle described in "Brideshead

Revisited." He was killed in Burma during World War II, when Caroline was 12.

Like other women of her class,

she skipped college; she moved to London and worked for Claud Cockburn, the

influential left-wing journalist. She recalled meeting Mr. Freud at that time at

a party memorable because the painter Francis Bacon caused a row when he hooted

down Princess Margaret, who had just started singing "Let's Do It." She and Mr.

Freud then became part of the group that included Bacon, Cyril Connolly and the

other artists and writers who gathered nightly to drink at the Gargoyle and

Colony Clubs.

When her marriage to Mr. Freud

ended in 1956, she installed herself at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles. She

got a tiny part in the television series "Have Gun Will Travel." Stephen Spender

asked her to write an article for Encounter magazine about California beatniks,

and it was ' sendup that launched her writing career.

She next moved to New York and

married Israel Citkowitz, an American composer and pianist, and a student of

Aaron Copland, 20 years her senior. They were divorced in 1972, when she married

Lowell, but they remained close.

During the next years she

endured a series of Job-like catastrophes: the death of Citkowitz; Lowell's

crippling manic depression and early death; the death from AIDS of her brother,

Sheridan, to whom she was very close; the death of her eldest daughter, Natalya,

after a drug overdose, and her own bout with cervical cancer, for which she had

an operation that left her in constant pain.

Throughout, she maintained her

dark humor and creatively transformed her experiences into her novels and

essays. "I think it's partly Irish," she once explained. "Irish people are very

funny but have this tragic sense.

"As Cal wrote," she added,

referring to Lowell, "if there's light at the end of the tunnel, it's the light

of the oncoming train."

In addition to her daughter

Ivana, of Manhattan, she is survived by her mother, of London; a sister, Lady

Perdita Blackwood, of Ulster; another daughter, Evgenia Citkowitz of Los

Angeles, and a son, Sheridan Lowell of Manhattan.

July 28, 2002, Sunday

THE CLOSE READER; Sing O Muse

(but Softly)

By Daphne Merkin

By the time I got to know her,

Caroline Blackwood had long since gotten out of the muse business. We met one

summer at the house of a mutual friend in Water Mill, on Long Island, who was

also the executor of her considerable fortune. (Her mother was a Guinness, and

Caroline grew up on an ancestral estate in Northern Ireland, where she inherited

not only her family's brewery wealth but their propensity for hard drinking.)

I was hugely pregnant, the day

was boiling, and Caroline and I struck up an instant rapport based on our shared

fear of the two large and excessively drooling dogs that were given the run of

the place, as well as our shared fascination with all forms of human oddity,

ranging from serial killers to transsexuals. (At the time of her death six years

ago, Caroline was writing a book about a transsexual she had befriended.) If you

didn't know, it would have been hard to guess that this woman of formidable

intellect and ambition, the author of novels of chilling charm as well as

several nonfiction books, had ever been content to play the helpmeet, and yet

even then she was famous mostly because of the three men she had been married

to: the painter Lucian Freud; the musician Israel Citkowitz; and the poet Robert

Lowell. Indeed, as the title of Nancy Schoenberger's biography, ''Dangerous

Muse,'' suggests, this aspect of her life all but overtook her life as a writer.

Real muses -- as opposed to the

ones men try to conscript from among the unwilling wives and girlfriends around

them -- have ever been in short supply. The pay is lousy, and it's not a

long-term position, to judge by the tragic fates of former muses like Camille

Claudel, who was consigned to an asylum after Rodin left her, and Dora Maar, one

of Picasso's many discarded love objects, who eventually disappeared and died in

Paris, something of a recluse, in 1997. Also, the job requirements aren't very

clear. Is a muse supposed to be an inspiration, or is she merely a devoted

amanuensis, like Véra Nabokov, who ended up with borrowed glory and a batch of

beautiful drawings of butterflies? Then there's the even more basic question: Is

being a muse a privilege or a predicament? At what point does a once

facilitating partner (an ''enabler'') mutate into a crazy wife, a self-deluded

presence like Zelda Fitzgerald or T. S. Eliot's first wife, Vivienne -- an

albatross to be schlepped along and jeered at by one's hardhearted or snobbish

friends (like Hemingway, who cast Zelda as a castrating villain almost from the

moment he met her, and Virginia Woolf, who in her diary characterized Vivienne

as a ''bag of ferrets'' around her husband's neck) until she is summarily

ejected and sent to the loony bin, whether she belongs there or not. (According

to Carole Seymour-Jones's recent biography of Vivienne, ''Painted Shadow,''

Vivienne's brother, Maurice, made a guilt-ridden admission shortly before he

died in 1980 that his sister ''was as sane as I was. . . . What Tom and I did

was wrong.'')

If there's anything that seems

essential to the idea of the muse, it's that she must be in possession of

Hörigkeit, that quality of abject submission only the Germans would be

compulsive enough to have a name for. Anna Freud, something of a daughterly muse

herself, conjured up a similar mind-set with the phrase ''altruistic

surrender.'' In her case, behind all the high-minded psychoanalytic theory lay

the rueful recognition that the spotlight -- the serious work -- was to be

reserved for male genius. As for gifted women, they had to be satisfied with

dancing around the perimeter rather than basking in the glorious center.

Alma Mahler, who was one of the

few successful serial muses, worked her way through a gaggle of geniuses,

including Gustav Mahler, Rainer Maria Rilke and Franz Werfel. Closer to our own

time, there is the British novelist Barbara Skelton, who, with no small amount

of irony, recounted her life as an unrepentant femme fatale in ''Tears Before

Bedtime'' and ''Weep No More.'' Skelton, who was married to Cyril Connolly and

George Weidenfeld and whose countless lovers included King Farouk, is a rare

instance of a muse who ran the show, in part because she seemed never to have

overestimated either her own charms (though a great beauty, she described

herself as a ''bun-faced'' child ''with slanting sludge-colored eyes'') or the

charms of her famous partners.

As I see it, the essential

problem with muses is that they mostly fail to live up to the hype, and end by

inspiring disdain rather than adoration. They become antimuses, destructive

influences like Yoko Ono, who reduced her much more gifted husband to being a

baby sitter while she bought up real estate and indulged her penchant for

avant-garde happenings. Similarly, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book of poetry,

''The Dolphin,'' Lowell in the same poem invokes Blackwood as a Lolita-like

enchantress with ''Alice-in-Wonderland straight gold hair'' and as a devouring

mermaid ''who serves her winded lovers bones in brine.'' At the far end of the

spectrum, poor Maureen Tarnopol in Philip Roth's novel ''My Life as a Man'' is

no more than an embarrassment at best and, at worst, a lethal impediment to male

genius. This wannabe muse is killed off for her conniving efforts to secure the

role, and is then further reduced by way of the novel's mortifying epigraph, in

which Maureen's dream of lighting her writer-husband's fire is lifted from her

diary and exposed in print for all the world to laugh at: ''I could be his Muse,

if only he'd let me.''

What about muses for creative

women? Needless to say, most men aren't interested (though occasionally someone,

like Leonard Woolf, will consent to be a caretaker). For the most part we have

to make do with the classic female postures of compliance and subterfuge. In a

collection called ''The Muse Strikes Back,'' I find our dilemma charmingly

stated in the poem ''Erato Erratum,'' by Verna Safran: ''The graces are always

women, never men, / So on my pedestal I stand, with itching toes / Posing as

Mother Mary or as Magdalen, / And wondering how you look without your clothes. /

By candlelight, my dear, I pick your brains; / When I'm alone, I put you in

quatrains.''

Daphne Merkin, a staff

writer at The New Yorker, is the author of the novel ''Enchantment'' and of

''Dreaming of Hitler,'' an essay collection. Judith Shulevitz is on leave.

July/August 2002-08-12

Great Granny Webster

by Caroline Blackwood

New York Review Books, 128 pages, $12.95

Corrigan

by

Caroline Blackwood

New York Review Books, 328 pages, $14.95

As good as these two novels are (and Great Granny

Webster, shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1977, is so funny, mordant, and

harrowing that it might be a lost novella by the young Evelyn Waugh), both still

risk being overshadowed by the notoriety of their author. The Anglo-Irish Lady

Caroline Blackwood (1931- 1996) bewitched many of the most creative and

intelligent men of her time: she married the painter Lucian Freud and the poet

Robert Lowell, obsessed the moody critic Cyril Connolly, was photographed by

Walker Evans (who may have fathered one of her daughters), and had affairs with

the editors Alan Ross and Robert Silvers, among others. Blonde, with intense,

staring eyes, she could be disorientingly silent in company and then, after a

few drinks, ribald, witty, and by all accounts irresistible.

Still, being a muse to genius wasn't enough for the glamorous Blackwood: she

wrote nine books, including a highly imaginative study of the Duchess of

Windsor, and when she died (alcoholism, cancer), she was embarking on a study of

transsexuals. Dryly unemotional, almost reportorial, her matter-of-fact style

enhances the deliciousness in her depictions of stiff-backed old ladies, London

playgirls, Irish con men, and fatuous journalists.

In the semi-autobiographical Great Granny Webster, set in a fifteen-year

period soon after World War II, the ancient matriarch is a model of somber

rectitude who spends most of her afternoons sitting bolt upright in a darkened

drawing room. "Never having wished to receive pleasure, or give it, she forced

one to admit that there was something admirably robust in the way she was

totally devoid of any newfangled and slavish desire to please." Still, her

daughter ends up talking to elves and fairies, her granddaughter takes "nothing

serious except amusement" (at least until she commits suicide), and her

great-granddaughter tends to stare disturbingly into space, looking "goggle-eyed

and tongue-tied."

Throughout, Blackwood's humor tends toward the grimly absurd. In one scene a

psychiatrist nearly rapes a semi-conscious woman who has tried to kill herself.

Rebuffed, he is so ashamed that he remarks self-pityingly, "'Have you ever

wished you were dead?' ... apparently quite oblivious of the tactlessness of his

question." The longest chapter of the book evokes the sheer awfulness of the

family's damp, crumbling ancestral pile, Dunmartin Hall: think of Gormenghast

inhabited by characters out of Monty Python or

Cold Comfort Farm.

In Corrigan—Blackwood's last novel—the widowed Mrs. Blunt finds her life

reinvigorated when she meets the wheelchair-bound Corrigan, who the reader soon

realizes is a quotation-spouting fraud out to charm the old lady for her money.

So what? says the widow's cook, after Corrigan disappears. "Corrigan was no

different from most men. They all try to get the most that they can squeeze out

of a woman. But he gave her a lot." At the end of this cleverly twisted tale

Mrs. Blunt's daughter is herself inspired by the absent Corrigan to dramatically

change her own unhappy condition.

Yes, Caroline Blackwood was quite a siren in life, but these handsomely reissued

novels show that she possesses the power of enchantment even now.

—Michael Dirda

Circe among the artists

Caroline Blackwood, the

muse of Lucian Freud and Robert Lowell, used her eccentric aristocratic

background as material for a memorable gothic novel, writes Honor Moore

Saturday August 3, 2002

The Guardian

In her first book, For All That I Found There, a

collection of fiction and non-fiction, Caroline Blackwood published a short

memoir that predicts the writer she will become. During the war, Blackwood had

been sent for safety to a boys' school, and the central character of her memoir

is the school bully, "gingery-haired, near-albino with a snout-like nose".

"Piggy" is about the interplay of sex and power, something Blackwood, a great

beauty, knew about. By the time she wrote the story in her 40s, she was an old

hand at navigating the minefields her allure for men had set, having served as

muse to Lucian Freud, whom she married and who painted her, and Walker Evans,

who took spectacular photographs of her. Her turn from journalism to literary

prose had followed her marriage in 1972 to the poet Robert Lowell, and the

inspiration of his life studies can be felt in hers.

"Freakishly over-weight",

Piggy McDougal holds sway over prepubescent Caroline and her male classmates by

violence and intimidation, and so, when he takes her out to a rhododendron grove

and directs her to remove her clothes, she does it. The little girl is

"mortified and humiliated", but the adult narrator turns boy to pig as cooly as

Circe:

"The nervous blink of his white eyelashes became far worse than usual. His mouth

was slack and trembly. He kept fidgeting with his hands... 'Have you had the

curse yet?' McDougal's porcine face, usually so florid, was ashen...

Instinctively I sensed that I must not tell him that I had never had it. When I

refused to answer, my silence seemed to chill him, for I noticed that his teeth

were chattering like those of a winter swimmer."

Blackwood followed For All

That I Found There with a short novel in which she engages what will become one

of her central themes: the turbulent involuntary ties between women. In The

Stepdaughter, an enraged self-absorbed woman is saddled with the sullen,

cake-addicted daughter of the philandering husband who has abandoned her. In

Great Granny Webster, Blackwood treats a related subject, once again with the

cauterising diction that distinguished "Piggy". Here she takes a writer's dive

into the material with which, as a raconteur, whisky in hand, she famously

enchanted and mesmerised her friends.

Blackwood, like Robert Lowell,

belonged to a tradition of troubled artist aristocrats whose bloodlines coursed

through the veins of imperial viceroys, Harvard presidents, Anglican bishops,

closeted aesthetes and vengeful daughters passed over by primogeniture. Rising

incendiary from august genealogies and privileged with huge dark houses,

unfettered inheritances or boundless land holdings, these descendants, before

burning out in a harsh glee of liberation, may mark the crawl of history - their

addiction or madness outdone in its display by their art. Blackwood counted

among her ancestors Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the Restoration dramatist, whose

drink and debt induced a plummet from nobility but not from the firmament of

English playwrights.

Drink was leagues ahead when

Blackwood emerged from the motherhood of four daughters, a youth of beauty in

Hollywood, New York and London, and a short career as a magazine journalist, to

become a writer to contend with. Seriousness would have been hard enough for

such a woman to achieve without the early loss of her father and a mother like

Maureen, Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, in her youth one of the Golden

Guinness Girls. The marchioness, neglectful and critical of her children, had

disapproved of her daughter's marriages to Freud and the composer Israel

Citkowitz, but when Caroline married Robert Lowell, she foraged the Guinness

genealogy and found Lowells: "Do ask Cal," she wrote her daughter, "if we were

already his kinsmen."

Blackwood and Lowell had met

for years in New York

literary circles, but the coup de foudre between the married American poet at

the height of his fame and the married Anglo-Irish noblewoman took place in

London, and, after 18 months of hectic courtship, the birth of their son, and

sad, hurried divorces, they married. If Lowell, hobbled by manic-depressive

illness, considered himself reborn as a poet when he fell in love with

Blackwood, the alliance transformed her from an occasional writer to a committed

one. It is sweet to imagine them settled in her house in the English

countryside, Lowell at work on The Dolphin , for which Caroline was his muse,

and Caroline, writing across the room, her entranced husband sneaking an

occasional look. Lowell

later described the scene:

Winterlong

And through the fleeting,

cool,

Kentish summer -

obstinately scowling

to focus your hypnotic, farsighted

eyes

on a child's pale blue paper exam

book -

two dozens... carpeting an acre of

floor,

while a single paragraph in your

large,

looping, legible hand exhausted a

whole book...

(from "Runaway", in Day by Day ).

The work that exhausted those

blue books was Great Granny Webster, a compressed virtuosic gothic story, whose

young woman narrator seeks to unravel the curse of her female inheritance as a

way of encountering her father, who died fighting in the Burma campaign when she

was nine. The Scottish great grandmother of the title, like Blackwood's own

paternal great grandmother, is the mother of a severely disturbed daughter

(based on Blackwood's grandmother), who has a psychotic breakdown and tries to

murder her grandson, the narrator's father, at his christening. Great Granny

Webster is only 135 pages long, but literary London greeted it as the coming of

age of a significant voice. A finalist for the Booker Prize, it lost to Paul

Scott's Staying On, the decisive vote cast by Philip Larkin, who reportedly

insisted that a tale so autobiographical could not stand as fiction.

It seems strange now that the

issue of verisimilitude could keep a book from a prize, but the forces of

literary innovation move slowly. Blackwood, perhaps defensively, once remarked

that Great Granny Webster was "probably too true", but 25 years later, its

truthfulness can be likened to the accuracy of true north. The book is a

distilled work of literary imagination that anticipates not contemporary

American memoir, in which a reader's interest is often summoned merely by a

writer's striptease of dysfunction, but the slim, intense novels of our time

that transmute from actual people and places narratives so true to their tellers

they cannot seem other than fiction to anyone else.

Like the young female

narrators of Marguerite Duras and Jamaica Kincaid, the narrator of Great Granny

Webster is revealed in the sensuality with which she recreates her own powerful

sense of place and in her reluctance to indulge sympathy for her characters at

the expense of her own absolute accuracy. While Duras and Kincaid evoke the

colonised tropics, Blackwood hearkens back to the environs of the coloniser, her

narrator a latter day Jane Eyre fearless in handling the gothic excesses of her

material - a line of women, each of whose madnesses fits inside that of her

predecessor like a nest of painted dolls.

It is as if Blackwood had

devised for her unnamed narrator, whom we assume to be a version of herself, a

path home through a gauntlet of gorgons and furies, into a maze. Will she freeze

into the miserly stoicism of her great grandmother, a woman always dressed in

black who spent her days sitting in a straight-back chair staring "silently in

front of her with woebegone and yellowy-pouched eyes", venturing out only to

creep along the seashore in a hired, chauf feur-driven Rolls Royce, her sole

companion an osteoporotic one-eyed maid? Or will she be seduced by the sensual

blandishments offered by her father's sister, her Aunt Lavinia, who attempts a

suicide as garish and colorful as great granny's old age is monochromatic? Most

frightening, will she inherit the kinetic madness of her winsome and sinister

grandmother, whose retreats into delusion lurch from fantastical to murderous as

she loses herself in a maze of terror and rage?

The maze is made physical in

Dunmartin Hall, family seat of the narrator's father, for which the model was

Clandeboye, where Caroline lived as a child. Vehement close-up observation,

insistence on reporting that does not flatter, and a preternatural ability to

communicate the feel of real cold, are elements in Blackwood's description of

the house where, as she has one visitor remember, "there always seemed to be a

bat trapped in his bedroom", and that the cold was such "he often found it

easier to get to sleep lying fully clothed on the floor-boards under a couple of

dusty carpets than in his unaired bed".

In these descriptions,

Blackwood is Merchant Ivory from hell, ripping into what they would score with a

gavotte: a vast, stone manor house, its wings torn down and rebuilt as fortunes

wax and wane over centuries; its leaks that prompt the retinue of resentful

footmen to wear Wellingtons to serve table; its pheasant reheated daily in

rancid lard; its filth, its wringing wet sheets, its lunatic mistress screaming

in the belfry, its bankrupt master thinking only of his poor, dear wife.

Dunmartin Manor threatens long after one finishes reading, an objective

correlative for inherited personal terrors that roil beneath the comely surfaces

of hereditary wealth, landed culture, and empire.

As Caroline worked on Great

Granny Webster, her relationship with Lowell fell apart. The vertiginous squalor

Blackwood ascribes to Dunmartin Manor must have been inspired by the

powerlessness she felt in the chaos of their last months, and her limning of the

grandmother's insanity suggests a source closer at hand than the nether regions

of family myth. Blackwood drank and drank, and Lowell drank with her, his

hallucinatory manic episodes exacerbating her anxiety, her tirades frightening,

provoking and finally enervating him. As she infused her novel with the energies

of their distress, Lowell sorrowfully chronicled the dolphin's transformation into a

mermaid who...

...weeps

white rum undetectable

from tears.

She kills more bottles than the

ocean sinks,

and serves her winded lovers' bones

in brine...

By the time Great Granny

Webster was set to be published, Blackwood and Lowell had finally separated.

Lowell, diagnosed with congestive heart failure, had decided by the autumn of

1977 to return to New York and to his previous wife, the writer Elizabeth

Hardwick. He died in the taxicab that brought him from the airport to her door,

a Lucian Freud portrait of Caroline in his arms.

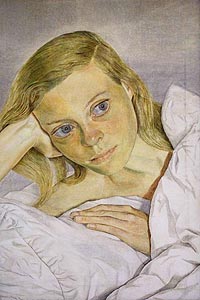

In the portrait, Caroline,

hair golden, lies on her side under white sheets, her eyes enormous and ocean

blue, a woman languorous and uneasy. But there was little languor in the

Caroline Blackwood who emerged from Lowell's death, a woman who, alcoholism

undiminished, produced six books in the 18 years before her own death from

cancer in 1996 at the age of 65. Her final book, The Last of the Duchess, is

once again the portrait of a woman in thrall. Wallis Simpson's marriage into

royalty forced a king's abdication and rocked the British Empire, but once a

widow she surrendered her freedom and died under virtual house arrest, her woman

jailer the lawyer she herself paid.

The graveyard ending Blackwood

devised for Great Granny Webster is no less ironic, but its final scene turns on

a striking poetic figure. The officiating priest's skin becomes "bright violet

blue" with cold as he recites the burial prayers, and great granny undergoes a

final and unexpected transfiguration. The narrator, survivor and witness stands

musing in the freezing air, the only other mourner her great grandmother's maid,

one eye obscured by a black patch, the other weeping.

Honor Moore is a poet and a

writer and author of The White Blackbird. This is an edited extract from the

introduction to a new edition of Caroline Blackwood's Great Granny Webster,

published by New York Review Books in October.

The Art

of Infidelity

Blackwood, Lowell, Plath, and

more. .

by Noemie

Emery

09/10/2001, Volume 006, Issue 48

|

IN 1959,

SYLVIA PLATH AND ANNE SEXTON, successful poets and failed suicides, took a

course given by Robert Lowell, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and manic

depressive, in the art of confessional poetry, the form in which all three would

specialize. After class, Plath and Sexton would meet for drinks at the Ritz

Carlton in Boston, to discuss poetry, Lowell, their various breakdowns, and past

and future suicide attempts.

In 1974, Anne Sexton closed her garage door and turn on the ignition, gassing

herself to death at forty-seven—following down the road her friend had traveled

in 1963, when, at age thirty, Sylvia Plath turned on the gas oven in her London

apartment, having first blocked the cracks in the doors so the fumes would not

hurt her two children, and thoughtfully set out their morning milk.

Their lives were dominated by scenes of poetry, marital infidelity, divorce, and

death. The connections and parallels among them seem almost infinite. Both Plath

and Lowell did time in McLean, a mental hospital specializing in Boston’s best

breakdowns. Plath spent five months, from August 1953 to January 1954, after she

had swallowed most of a bottle of sleeping pills and crawled into a basement

to die. Lowell entered McLean for the first time in 1958, and would return

three more times after that. At the time of her death, Plath was married

to—and separated from—Ted Hughes, a young poet of infinite promise who would

later become poet laureate of England before he died in 1998. |

|

|

|

By the time of his own

death in 1977, Lowell had been married three times, to the short-story mistress

Jean Stafford, the elegant essayist Elizabeth Hardwick, and the British

aristocrat, Lady Caroline Blackwood—who had married three artists herself: the

painter Lucian Freud, the composer Israel Citkowitz, and Lowell in 1972.

The first biography of Caroline Blackwood, Dangerous Muse, by Nancy Schoenberger,

has recently been published—joining at the bookstores the unexpurgated version

of Sylvia Plath’s journals and Sylvia and Ted, a novel about Hughes and Plath’s

marriage by British writer Emma Tennant, who, in the 1970s, had an affair with

Ted Hughes. In fact, it was Emma Tennant’s brother, Lord Glenconnor, who first

owned Girl in Bed, Lucian Freud’s most famous painting of Caroline Blackwood,

which he later sold to Robert Lowell. And it was at a party in 1979 at the home

of Emma Tennant that Blackwood’s oldest daughter, Natalya, was given by

Tennant’s nephew the dose of heroin from which she would die.

HAD THEY LIVED, Plath and Blackwood would today be seventy. When Plath died at

thirty, she looked much like a schoolgirl. When Blackwood died in 1996 at age

sixty-four, she resembled a crone. The two were alike in nothing—and

simultaneously alike in too much.

Plath was American, born to Austrian immigrants, from the cash-strapped and

striving middle class. Blackwood came from the aristocracy: monied, cold, and

overripe. Plath was inse-

cure, Blackwood self-confident. Plath was bourgeois, Blackwood bohemian. Plath

was a perfectionist, an early Martha Stewart, who kept house by the rule of the

women’s magazines she loved and devoured. Blackwood was a sloven, turning any

home into a hovel in short order. Plath wrote from childhood and was nationally

published while still a teenager. Blackwood began writing late in her thirties.

Plath was not technically beautiful, but still fit the mold of mid-1950s good

looks, while Blackwood had stunning and "heart-stopping" beauty. Plath’s life

was broken by a femme fatale, who walked off with her husband. Blackwood was

such a femme fatale, who took two of her three husbands away from their wives

and their children. Both Plath and Blackwood had a drive toward darkness and

death.

LADY CAROLINE BLACKWOOD was born in Ireland in 1931, into the tranche of society

that gave us the Mitford sisters: original, arrogant, gifted, and bent. From her

father’s side came descent from a line of lords and landowners (and the

playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan). From her mother’s came the Guinness

brewery fortune, on which she sustained herself and her series of indignant

husbands. From the start, Caroline showed a mordant sensibility wholly at odds

with her angelic appearance. She was "disturbing but exciting," her friends

report. She conveyed a "negative excitement"; "there was an extraordinary

quality which I can only describe as a brilliant darkness"; "she was like a

radiant disease." Said one close friend, Xandra Gowrie, "At every crossroad she

saw someone being run over and mangled. Almost every minute of her life, she saw

an appalling disaster happening right in front of her eyes."

To a certain kind of male artist, this combination would prove irresistible, and

Caroline began at eighteen her lifelong career of attracting men who were not in

great shape when she met them, thrilling them for a while, and leaving them

burned out, embittered, or dead. "She chose her men for their instability and

their looks," said one observer. Her first husband was Lucian Freud, grandson of

Sigmund, darkly handsome, and none too stable. "Lucian was a very unfaithful

husband," one of her friends notes. "Lying awake at night, it’s like counting

sheep, trying to figure out who his children are."

Freud painted a series of lyrical portraits, notably Girl in Bed (1952), which

shows Caroline as fawn-like and luminous. But two years later, in 1954, when he

painted Hotel Bedroom, the mood had notably darkened. Caroline looks

anxiety-ridden, and Lucian Freud put himself in the picture "as if he had been

skinned alive with his own hand." Two years after that, Caroline left him.

"Lucian’s painting changed violently after I left him," she later said. What

certainly changed was his opinion of women: The tender portraits of his early

years gave way to repellent and monstrous nudes.

CAROLINE’S SECOND HUSBAND was the American composer Israel Citkowitz, once a boy

wonder, who looked almost identical to Lucian Freud—who himself resembled Robert

Lowell in his younger years. Caroline (one struggles to phrase this delicately)

had three children while married to Citkowitz, and she seems to have married him

in hopes of reviving his dormant creative abilities. Instead, he became a

housemaid. "Caroline had Israel doing laundry," a friend of the couple

complained. "He devoted himself to the children, while Caroline drank."

Having broken him down to the status of floor mop, Caroline moved back to London

in 1970. But Citkowitz followed her, moving into the second floor of her

townhouse, where he lived more or less as a nurse. His apartment was

"catastrophic," said Jonathan Raban. "It always looked burgled. Once I stopped

by and couldn’t find him, so Caroline said I should call the police. I did, and

when they came in they were alarmed, and thought that the place had been

burgled. I told them he always lived like that."

Meanwhile, Caroline, too, had deteriorated, drinking heavily and living in

squalor. "She created a shambles wherever she went," said one acquaintance.

Another recalls her talking brilliantly, with empty bottles rolling at her feet.

She was also becoming a serious writer, starting with a request from Stephen

Spender to review movies for his magazine. Her subjects would always be grim and

depressing. As a friend noted, "Caroline...was a learner. She learned from her

husbands. She had that magic thing that crossed the line of fantasy and

metamorphosed into something creative. She loved to tell stories...always with a

bad ending! It had to have that kick."

BUT, WITH HER ARISTOCRATIC entrée and her bankbook, Blackwood could afford to be

dissolute. Sylvia Plath had no leeway at all. The signal event of her life was

her professor-father’s death when she was eight years old. It removed both an

emotional stay and her family’s main source of income. From then on, her mother

sacrificed herself to her children—with the understanding that success would be

enormous when it came.

Sylvia tried. She was published at eight in local newspapers, given a

scholarship to Smith College, and awarded a guest editorship in the annual

college issue of Mademoiselle magazine. She strained to become the model of

complete excellence: poet and prom queen, dazzling soul of the American coed.

She even briefly dyed her hair blonde. She wanted to have it all, to be John

Donne and Martha Stewart, to write great works, have a great love, be a great

mother, and graciously run an immaculate home.

The strain could be immense. In his poem "The Blue Flannel Suit," Hughes catches

the edge of her terror:

Costly

education had fitted you out....

What eyes waited at the back of the class

To check your first professional performance

Against their expectations. What assessors

Waited to see you justify the cost.

The cost

was occasional bouts of "frozen inertia," as Plath wrote in her journals. "You

felt scared, sick, lethargic...not wanting to cope...colossal desire to escape,

retreat, not talk to anybody....Fear of not succeeding. ...Fear of failing to

live up to the fast and furious prize-winning pace of these last years." Back

home in Wellesley, after her stint in New York, she was rejected by a writing

class at Harvard’s summer school, and she went into a tailspin, attempting

suicide. Found in the cellar by her mother and brother, she was sent to

McLean—and discharged five months later as cured.

In 1955 she won a Fulbright scholarship to England, and she impressed the

British, still drained from the war, with her American vigor and bounce. In his

first poems, Hughes cites her endless legs, her "American grin," her "long hair,

loose waves—your Veronica Lake bangs. Not what it hid." "What it hid" was the

scar from electric-shock treatment. This scar, masked by the blonde sweep of

normalcy, was his permanent image of Plath.

TALL AND TALENTED, hungry and fierce, the poets seemed made for each other.

There was work, there were books, adorable children, a picture-book cottage in

Devon. In Sylvia’s eyes, the whole thing was heaven. For Hughes, as Tennant

pictures him in her novel, the picture was blacker. There were panics,

outbursts, bad dreams of her father, dark fears. Sylvia, Tennant says, could not

laugh or relax. "Sylvia always makes too much of a fuss. A headache, a tiny burn

from the recipe she worries over hour after hour, is enough to bring grief,

anger, hysteria." Always, there is the need to seem perfect. And then, the

perfect world is blown apart.

In 1961, the Hugheses left their London flat for a new house in Devon,

subletting their apartment to David Wevill, a Canadian poet, and his wife, Assia

Guttman, a ravishing beauty, thrice married, with an international and exotic

past. In the spring of 1962, Ted and Sylvia invited the Wevills for a weekend in

Devon. They arrived on Friday and left on Sunday, and on Monday, Hughes was on

the train to London to begin his affair with Assia Wevill.

"IN THE NEXT WEEKS," Tennant says, "Sylvia wrenches the telephone cord from the

wall...makes a bonfire of her husband’s manuscripts...feeding the flames with

his hair clippings, nails...drives the station wagon off the road." Distraught,

feverish, losing weight, Sylvia begins to pour out her Ariel poems, long screams

of rage at her husband and father. In the fall of 1962, both Ted Hughes and

Sylvia Plath move, separately, back to London. Sylvia starts an affair that does

not make her happy. She makes a surprise visit to Hughes’s flat and sees that

Assia is pregnant. Days later, she turns on the gas.

Curiously, Caroline Blackwood’s next affair also began with housing in London.

In the summer of 1970, Robert Lowell went to a party in London to see Xandra

Gowrie and stayed too late to go back to Oxford, where he was teaching. So,

Gowrie reports, "I turned to Caroline and said, ‘Caroline, you’ve got lots of

room, you have him,’ and they left together, and that was that." Lowell went

home with Caroline Blackwood and, in some senses, never moved out. He began work

on volumes of poetry that celebrate Caroline as an enchantress—and enrage many

by including passages from letters from his anguished wife, Elizabeth Hardwick,

and Harriet, their little girl. In September 1971, Caroline bore Lowell a son

named Sheridan, a year before they married.

As with Hughes and Plath, Lowell and Blackwood seemed made for each other,

sometimes in ominous ways. "They were both drinkers, and clever," said Xandra

Gowrie. "They both smoked endlessly, and didn’t wash much....Both lived near the

edge." Lowell often went over it, into manic delusions. This had been handled as

well as possible by the stable and motherly Hardwick, but Blackwood was a

different matter. As Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald had proved decades earlier,

alcoholics and the mentally ill may enchant one another, but do not wear well.

"We’re like two eggs cracking," Lowell wrote. Lost once again in emotional

transit, he began to be worn down by anxiety. In 1977, he died of a heart attack

in a New York taxi on his way back to Elizabeth Hardwick—Lucian Freud’s

portrait, Girl in Bed, in his arms.

By this time, Caroline no longer resembled the girl in that portrait, her beauty

eroded by drinking and strain. In 1976, she had produced a short novel, The

Stepdaughter, which was widely praised. In it, the heroine deeply resents the

unlovely child foisted on her by her renegade husband. In particular, the novel

is a savage portrait of her daughter Natalya, her least gifted child, and the

one least able to cope in her chaotic household. By 1978, the seventeen-year-old

was addicted to heroin. She died a year later, having drowned in her tub.

Caroline’s nihilism was deepened and darkened by guilt. "She saw Natalya’s death

as a suicide she had caused," a friend said, correctly. "She saw how destructive

and cruel she had been."

FOR THE REST OF HER LIFE, she would shuttle between London and the house that

she bought on Long Island, writing amid her chaos and squalor. Empty bottles

were the usual décor of her dwellings, and she was put on a list of unwelcome

visitors by some of the country’s leading hotels. Before she reached fifty, her

hair had turned white, and her face had coarsened beyond all recognition. The

darkness inside had at last become visible. A moralist might say she had the

face she deserved. The end came in 1996, from cervical cancer, though she had

never recovered from the deaths of Natalya and Lowell, and from her own part in

causing them. "She was furious that her dream of love had not been realized in

Lowell," said one of her lovers.

Need one point out that this was Sylvia Plath’s complaint against Ted Hughes?

Three weeks after Plath’s suicide, Assia Wevill aborted her child. Six years

after that, she too gassed herself, killing also her small daughter, Shura, the

out-of-wedlock child that she bore to Ted Hughes.

Hughes never wrote of this later catastrophe. But near the end of the 1970s he

began to write the verses that make up Birthday Letters, the long sequence of

eighty-eight poems that trace his relationship with Sylvia Plath from before

their first meeting (when he sees a picture of the Fulbright scholars) to the

years after her suicide, as he tries to cope with their distracted children,

listening to the howling of wolves. Hughes slights his own role in her suicide,

seeing himself, Assia, and Sylvia as victims of destiny, actors performing roles

in a prescripted drama:

You wanted

To be with your father

In wherever he was.

And your body

Barred your passage

And your family

Who were your flesh and blood

Burdened it.

It’s

certain that Hughes is much to blame; having one’s husband get another woman

pregnant does not make a girl happy. But even before his infidelity—even before

their marriage—Sylvia Plath had been more than half in love with easeful death.

It was not Ted Hughes who led her into that basement in Wellesley or who

prompted the cheerful discussions of self-termination in her girl-talking

sessions with Anne Sexton. Indeed, according to Sexton, it was Plath who first

brought up the topic, telling "the story of her first suicide in sweet and

loving detail."

SYLVIA PLATH WAS A BRITTLE REED, waiting to break whenever a rejection hurt the

image of her own perfection—as the 1953 rejection by Harvard broke her

temporarily, as the 1962 rejection by Hughes broke her forever. The girl who

insisted on having it all could not bear to have less than everything. And so,

she chose to have nothing at all.

Noemie Emery is a

contributing editor to The Weekly Standard.

November 19, 2010

Shaking the Family Tree

WHY NOT

SAY WHAT HAPPENED?

A

Memoir

By Ivana

Lowell

Illustrated. 285 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $27.95

This summer, an idealistic young New Yorker spent several weeks working with

poor children in India. Just before she left, a little girl ran up and pinched

her so hard she drew blood. When a translator asked why she’d hurt someone who’d

been kind to her, the girl explained, “This way she won’t forget me after she

leaves.” That startling child already knew the inscriptive power of pain.

In her

memoir, “Why Not Say What Happened?,” Ivana Lowell, the Anglo-Irish Guinness

heiress and the daughter of the glamorous, troubled writer and writer’s muse,

Lady Caroline Blackwood, shows she also learned that lesson early. When she was

6, living in the British countryside in a grand, damp Georgian pile called

Milgate Park, Lowell overturned a kettle of scalding water on herself, covering

70 percent of her body in third-degree burns. Her mother and stepfather, the

American poet

Robert Lowell,

slept on the floor of a hospital corridor as she fought for life. Lady Caroline

was a self-dramatizing alcoholic, Lowell a manic-depressive genius. Their lives

were consumed by creative productivity and social mingling with intellectuals,

aristocrats, poets and artists. But in this instance, Ivana was their focus. She

appreciated the attention.

In a sonnet to his stepdaughter, Lowell wrote, “Though burned, you are hopeful,

accident cannot tell you / experience is what you do not want to experience.” In

her book, whose title comes from her stepfather’s poem “Epilogue,” Lowell takes

stock of the physical and emotional wounds that have shaped her: “It would be

intolerable if one’s nerve endings and memory were in tune.” She surveys her

scars with pride — as if they were hard-won badges, marking an unending battery

of personal endurance tests.

There was the sexual abuse she endured as a child from an odd-jobs man who

worked at Milgate Park. There was the sudden death of her stepfather in 1977, of

a heart attack, as he sat in a taxi in New York, clutching an old portrait of

Lady Caroline painted by her first husband,

Lucian Freud.

There was the sudden death, in 1978, of Lowell’s older sister Natalya (daughter

of the pianist Israel Citkowitz, their mother’s second husband), of a heroin

overdose. In 1996 came the death of her mother, of cancer, at the Mayfair Hotel

on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, in a suite of rooms arranged by Lowell’s

boyfriend at the time, Bob Weinstein of Miramax. The author describes the scene

as “a bit of a circus,” which is putting it mildly. One visitor, the singer

Marianne Faithfull, showed up in tight leopard-skin pants, “sprawled across my

mother’s bed, dislodging all her tubes,” and belted a version of the song

“Surabaya Johnny.” (“Was that rather wonderful,” Lady Caroline asked afterward,

“or was it really, really awful?”)

Three years later, in 1999, came the fiasco of Lowell’s wedding at the Rainbow

Room, which took place during a union strike. Her half-brother Sheridan (son of

Robert Lowell) joined the picket line in black tie, shouting at the guests.

Their cousin Desmond Guinness took in the ruckus with glee, exclaiming, “I

haven’t seen a crowd this angry since my mother married Oswald Mosley!” The

groom, who had been sober — as far as the bride knew — for more than a decade,

took this occasion to become “completely high.” Their baby was due in four

months. If Lady Caroline had been alive on the wedding day, she probably would

have joined her daughter in their favorite refrain: “It’s too bad, even for us!”

Despite the grimness such a litany might bespeak, Lowell clearly feels some

triumph at her survival of these ordeals, and admires her mother’s achievements

in spite of her addiction: “No matter what kind of night she had passed,

stomping around, drinking and ‘catastrophizing,’ in the morning she would get up

early, pour herself a strong cup of coffee and sit down with her notebook to

write.” Caroline Blackwood was the author of 10 books, notably “The Last of the

Duchess,” an account of Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, and her maniacal

protectress, the lawyer Maître Blum, who guarded access to her in her final

years. Lowell calls that book “funny, ghoulish and sharp.” The same can be said

of the gallows humor she brings to her own history.

Lowell does not so much condemn as commemorate her afflicted mother and the

alcoholism — “the family problem,” she calls it — that plagued them both. “In

her own shambolic, heartbreakingly inadequate way, Mum had always been home” to

Lowell, she explains; and the alcoholic atmosphere that permeated that home

looms too large in the author’s memory for her to abjure it. Drinking, for her,

has been “the only time I ever felt O.K., as if I were acceptable,” she writes.

“I was powerless over alcohol long before I ever had my first drink.”

As an adult, Lowell has been in and out of rehabs, detox programs and emergency

rooms: “I was good at being in rehab. Rather like boarding school, it felt safe

and uncomplicated.” But she agonizes about the consequences her ups and downs

may have on her daughter, Daisy (who is now 11). “I wanted so much to give my

daughter the sense of stability that I never had, but when you are drowning

yourself, how can you keep someone else afloat?” Her own mother hadn’t been much

of a life preserver, but Lowell had kept her chin above the waves. She hoped

Daisy would evince similar fortitude: “I prayed she would be able to navigate an

easier path than I had managed.”

Soon after her mother’s death, Lowell also lost her father, in a way. She

learned that Israel Citkowitz, the father of her older sisters, Natalya and

Evgenia, was not her own biological parent. She’d long heard hints that her

“real” father might have been either Ivan Moffat (a British screenwriter who

told her “spiteful” anecdotes about her mother’s missteps in Hollywood in the

late ’50s) or Robert Silvers, the editor of The New York Review of Books (a

“wise and sane presence” in her childhood, who sent her care packages of books

when she was at boarding school). Investigating, she learned that both Moffat

and Silvers believed themselves to be her father. “Why had they stood on the

sidelines?” she wondered. Eventually, a DNA test put the mystery to rest. “I had

done quite well without them — well, no, I hadn’t actually. But having an