|

Arts

Extra: The Prince of Reportage

Ryszard

Kapuscinski, chronicler of Third World, explores his time in Africa

in a new book

May

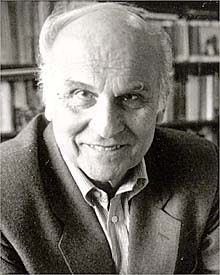

3 - The Polish

journalist and author Ryszard Kapuscinski is sitting in a corner

armchair in the stately, book-lined Midtown apartment of his editor

and friend, Sonny Mehta. Mehta isn't home-no one is-but the "shy"

Kapuscinski (his word) is filling up the still apartment with words.

THE

FORMER POLISH PRESS AGENCY correspondent is talking about his

staggering, ongoing career as chronicler of the Third World; his new

book on Africa, "The Shadow of the Sun" (published by

Knopf); Idi Amin ("I knew him, a very stupid man"); Julius

Nyerere ("a great intellectual"); Herodotus ("a great

reporter, the father of reportage-I'm doing a book on him");

the intrepid World Cup midfielder Zbigniew Boniek; the aphorisms of

E.M. Cioran; Curzio Malaparte, the Italian correspondent; Zanzibar,

and the great desert. Now he's talking about fear: "Fear is a

feeling everyone has," he says enthusiastically, in a

deliberate, accented English, that, for some reason, makes him

self-conscious. "But the difference is some can dominate fear

and others can't."

Meaning? "If you want to be there, in a place, if you

have to be there, and you're so dedicated to really reaching your

goal you don't think about the fear. And when you're in a dangerous

situation, it always looks more dangerous from afar than from inside."

Kapuscinski would know. While reporting on some 30

revolutions, he was a match flick away from incineration in Nigeria

after being doused with benzene, sentenced to death in Congo and

survived a shoot-out in the Honduran jungle. He had cerebral malaria

that left him unconscious in a dilapidated hotel room for three days

and a case of tuberculosis that nearly ended his foreign-reporting

career prematurely. He went eyeball-to-eyeball, nearly, with a

diabolical Egyptian cobra, got a flat in the Serengeti and was

surrounded by lions and nearly capsized in a petulant Zanzibar

Channel. Each time, Kapuscinski was saved by chance or the anonymous

hand of humanity.

"There was much more," he says, laughing, "but

I don't want to just write about those adventures. It would be

boring."

So the most remarkable thing about the 69-year-old

Kapuscinski-and there's a lot-is that he's even alive at all. His

hair on the sides, which is all he has, is white but he looks fit

and healthy. He's just revisited Latin America for what will be the

second part of a trilogy of observations and recollections, followed

by a volume on Asia, especially the Islamic world.

"The Shadow of the Sun" is the first part and takes

him back to the place he's most closely associated with: Africa.

It's his sixth book translated into English, though he has 20 out in

Poland (the country he always returns to, sometimes after years away).

He's been translated into 30 languages and speaks six himself:

French, Portuguese, Spanish, Russian, English and his native Polish

(the language he always writes in), with a working knowledge of

Swahili and Arabic.

His titles are iconic: "The Emperor" (on Haile

Selassie), "The Shah of Shahs" (on the last Shah of Iran),

"The Soccer War" (a series of short pieces from Latin

America and Africa), "Another Day of Life," (his

just-back-in-print sleeper about Portugal's withdrawal from Angola

in 1975) and "Imperium" (on the fall of the Soviet Union).

The Selassie and Iran books are his anomalous masterpieces, like

nothing before or since. Both are slim, less than 200 pages, both in

three parts. The emperor's fall is told through the sycophants who

surrounded him, but it ends up being a larger meditation on the

nature of authoritarian rule, Ethiopia serving as the backdrop. The

Iranian revolution is reiterated through photographs scattered on

his desk. And as if with a long telephoto lens, he focuses on the

exact moment a revolution becomes a revolution: when the

demonstrator no longer fears authority.

Kapuscinski says he was attracted to these parts, these

circumstances, from his own upbringing in Pinsk (now located in

Belarus) during World War II. "I think partially it was my

childhood. This was the poorest part of Europe, still is. My parents

were schoolteachers but when the war came there was terrible hunger,

poverty, the winter was coming, I had no shoes. I know what it means

to have no shoes, I know what it means not to eat for several days,

I know what it means when there's shooting. So in places like Africa

I feel very much at home. I understand them, and I communicate with

those situations. I'm empathetic."

But it's more than empathy that makes Kapuscinski Kapuscinski.

For one, it's his personality. He's not a Type A: he readily admits

fear, gets sick and weak, gets lost (and asks for directions), gets

beaten up, robbed, made the fool of, depressed. There's an ego there,

for sure, and ambitions ("my ambition," he'll say now,

"is to invent my own style of writing, my own genre of writing"),

but somehow he's different from, say, some of the brawnier

correspondents of today, who, you sense, are angling for a contract

from Tina Brown or a handsome mid-six-figure book deal or (better

yet) movie rights. Or a TV camera. Kapuscinski only envied the guy

with the Zenith shortwave radio.

Then there's his approach: he's insightful but never

patronizing. He obviously has an affinity for the culture, but it's

without sickening white guilt. He's an acute observer who finds the

extraordinary in the quotidian.

In his new book, in a piece of impressionism on Ghana, he

writes: "I arrived in Kumasi with no particular goal. Having

one is generally deemed a good thing, the benefit of something to

strive toward. This can also blind you, however: you see only your

goal, and nothing else, while this something else-wider, deeper-may

be considerably more interesting and important."

Kapuscinski finds that "something else" takes it,

makes it a fable or collects them and makes a collage or brings a

character to life.

Later in the book, describing the bureau chief of Agence

France Presse in Nairobi, he writes: "He knew everything."

Kapuscinski didn't know everything, and didn't think he did and was

open to discovery. He posed questions, even if he found some to be

unanswerable.

And there is lots that is unanswerable in Africa. He got

there in the hopeful late 1950s, the end of colonial rule, Africa's

Great Leap Forward, but over the decades saw parts of the continent

disintegrate into warfare-often fought by children-and famine and

disease.

The short pieces in the book reflect this. Some are more

dramatic than others, some are cautionary, some are searing primers

(on Rwanda, Liberia, Sudan and Uganda under Amin), some are just odd

and little (and beautiful) Kapuscinskian tales. Good 20th-century

European that he is he eschews plot for the great or small episode.

The book is not without repetition. He makes the point more

than once that he could've moved to the more livable parts of town

but always turned down those opportunities. "How else can I get

to know this city? This continent?" (It's a point, too, he

makes in "The Soccer War.") And the book seems to reflect

a European (or is it universal?) awe/fascination with the physique

of the black male: "a powerful, well-built young man named

Traore"; Habyarimana, the Radovan Karadzic of the Hutus,

"is massively built, powerful...."; "The driver ...

was like the majority of his countrymen, tall and powerfully built.";

"he was a brutal, greedy large man"; "with their

strength, grace, and endurance, the indigenous move about naturally...."

Still, it's as good as Kapuscinski has given us.

Geography and the unforgiving climate, as the title suggests,

is a leitmotif and he describes heat richly and differently somehow

each time. In the Mauritanian Sahara: "The night chill had set

in, a chill that descends abruptly and, after the burning hell of

the sun-filled days, can be almost piercingly painful." In

Monrovia: "Dusk too is stifling, sticky, slimy. And evening?

The evening steams with a hot, smothering mist. And Night? Night

envelops us like a wet burning sheet." In Timbuktu: "The

heat curdles the blood, paralyzes the body, stuns."

All along, and everywhere, even amid despair, there is grace

and Kapuscinski takes us there. What's missing, intentionally (and

thankfully), are specific political details. "I'm not a

political writer," he says. "I don't like to talk about

politics, and I'm not a specialist. My attitude, my approach, is

cultural anthropology-and literature. I don't talk to political

leaders, never. Besides politics is a big mess. It's not interesting,

and everything is changing so quickly. It's a waste of time."

Although he must realize that he's revered by writers,

editors and readers the world over he says only: "To do this

work you have to be very modest."

He's hoping to convince Sonny Mehta to publish his aptly

titled Lapidarium series of shorter observations and experiences

from his travels. Then he'll be writing-and traveling, and writing

and traveling some more, using his usual methods. "I feel very

bad in five-star hotels," he says. "I feel awkward. I like

to make things for myself, not to be served."

And the danger? The fear? "I've become an optimist,"

he says. "I trust people."

By

Michael J. Agovino

in

Newsweek, May, 28, 2001

|