2-10-2002

TAMARA DE

LEMPICKA

(1898 -

1980)

| |

When someone mentions the Roaring Twenties,

it conjures up the Jazz Age, flappers, Prohibition, the Charleston,

gangsters, The Great Gatsby, Mary Pickford, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Designers

and architects also remember the 20's for the Chrysler Building, the luxury

liner Normandie, and the interior of Radio City Music Hall, all outstanding

examples of the decorative arts style called Art Deco.

To many

designers of jewelry, furniture, clothes, fabrics, and ceramics, Art Deco of

the 20's with its geometric motifs and bright, bold colors represents the

best and purest forms of that decorative art period.

Art Deco,

a classical, symmetrical, rectilinear style that reached its high point

between 1925-1935, drew its inspiration from such serious art movements as

Cubism, Futurism, and the influence of the Bauhaus. In Paris, it was a

dominant art form of the 1920-1930 period.

Of all the

artists pursuing the style "Arts Decoratifs", one of the most memorable was

Tamara de Lempicka.

She was

born Maria Gorska of well-to-do parents in turn-of- the-century Poland.

After her mother and father divorced, her wealthy grandmother spoiled her

with clothes and travel. By age 14 she was attending school in Lausanne,

Switzerland.

Tamara

vacationed in St. Petersburg with her Aunt Stephanie, whose millionaire

banker husband had their home decorated by the famous French firm Maison

Jansen. All this high living gave the young girl an idea of how she wanted

to live and what her future should be. |

|

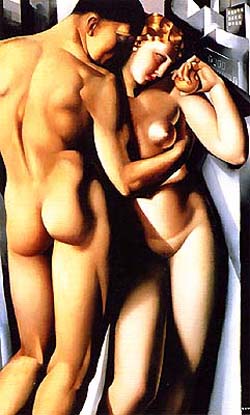

Adão e Eva |

|

Soon after Russia and Germany declared war in

1914, she fell in love with the most handsome bachelor in Warsaw, a lawyer named

Taduesz Lempicki. She set her sights on him and two years later they were

married in fashionable St. Petersburg. Her banker uncle provided the dowry, and

Lempicki, who had no money of his own, was delighted to marry this beautiful l6

year old girl.

A year later, Taduesz was arrested by the

Bolsheviks, and Tamara braved the Russian Revolution to free him, using her good

looks to charm favors from the necessary officials. The couple fled to Paris and

that's where the story of Tamara de Lempicka's fantastic life really begins.

Now known as Tamara de Lempicka, the refugee

studied art and worked day and night. She became a well-known portrait painter

with a distinctive Art Deco manner. Quintessentialy French, Deco was the part of

a exotic, sexy, and glamourous Paris that epitomized Tamara's living and

painting style.

Between the wars, she painted portraits of

writers, entertainers, artists, scientists, industrialists, and many of Eastern

Europe's exiled nobility. Her daughter, Kizette de Lempica-Foxhall wrote in her

biograpy of Tamara De Lempica Passion By Design, "She painted them all,

the rich, the successful, the renowned -- the best. And with many she also slept.

The work brought her critical acclaim, social celebrit and considerable wealth.

At the threat of a second World War, she left

Paris for America. She went to Hollywood, to become the "Favorite Artist of the

Hollywood Stars". She and her second husband, Baron Raoul Kuffner, one of her

earliest and wealthiest patrons, moved into American film director King Vidor's

former house in Beverly Hills.

The Baron and Tamara moved to New York City in

1943, to a stunning apartment at 322 East 57th Street, in whose two-story north

light studio she continued painting in the old style for another year or two.

Tamara decorated the apartment with the antiques she and the Baron had rescued

from his Hungarian estate. When the war was over, she reopened her famous Paris

studio in the rue Mechain, redecorated in rococo style.

Friends then asked her to decorate apartments in

New York City with her individual touch. After the Baron's death in 1962, she

moved to Houston to be near her daughter Kizette. She began painting with a

palette knife, much in vogue at the time.

The Iolas Gallery in New York exhibited her

newest and latest paintings in 1962, but the critics were indifferent, there

were not many buyers, and she swore to herself that she would never exhibit

again.

The advent of Abstract Expressionism and her

advancing age halted her career in the 1950's and 1960's. Somewhat forgotten,

her work ignored, she continued to paint, storing her canvases, new and old, in

an attic and a warehouse.

In 1966, the Musee des Arts Decoratifs mounted a

commemorative exhibition in Paris called "Les Annees '25". Its success created

the first serious interest in Art Deco.

This inspired a young man named Alain Blondel to

open the Galerie du Luxembourg and launch a major retrospective of Tamara de

Lempicka. It was a revelation in the art world and was to have been followed by

an exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery in New York City but Tamara, ever

imperious, made too many demands on how the exhibit was to be mounted, and the

curator at Knoedler walked away. Gradually, as Art Deco and figurative painting

came into favor again, she was rediscovered by the art world .

In 1978 she moved to Mexico permanently, buying a

beautiful house in Cuernavaca called Tres Bambus, built by a Japanese architect

in a chic neighborhood. She despaired of growing old and in her last years

sought the company of young people. She mourned at the loss of her beauty and

was cantankerous to the end.

Tamara de Lempicka died in her sleep on March 18,

1980 with her daughter Kizette at her side. Her wish to be cremated and have her

ashes spread on the top of the volcano Popocatepetl was carried out.

Tubular belles

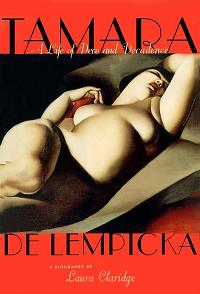

Tamara de Lempicka's life was sensational... so

are her biographer Laura Claridge's claims for her art

Laura Cumming

Observer

Sunday March 26, 2000

Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of

Deco and Decadence

Laura Claridge

Bloomsbury £25, pp436

| |

LES DEUX

AMIES |

|

There is a nude by Tamara de

Lempicka, now owned by Jack Nicholson, that summarises her deco style in one

metallic sweep. It's a painting of an odalisque, reclining in narcissistic

rapture, one arm casually flung behind her head. The pose is traditional, but

the arm is a polished tube, the body a gleaming auto with haunches like fenders

and hubcaps for breasts.

Run your eyes over this model,

the picture leers, note that streamlined bodywork, those red enamel lips. No

artist has ever made the equation between cars and women quite so explicit. Soft

porn, hard chrome - that's the Lempicka nude.

La Belle Rafaela is described

by Laura Claridge as the supreme example of Lempicka's 'painterly genius'.

Claridge is a hardcore fan, along with collectors like Nicholson, Madonna and

Luther Vandross, and her biography is a strategic campaign to restore Lempicka

as 'one of the twentieth century's most important artists'.

Since she believes that

Lempicka's art has been overshadowed by the story of her life, you might think

that a biography of this astonishingly vainglorious socialite was not the place

to start. But Claridge is no fool. In America, where this book was first

published, the only way to get art history on to the nightstands of Hollywood

and Manhattan is to wrap it up in a sensational life.

Tamara de Lempicka was born in

Moscow around 1895 - she preferred Warsaw in 1902 - to a family of

Polish-Russian aristocrats. In 1916, she married the rich tsarist Tadeusz

Lempicki and they might have lived an entire life of sybaritic leisure if the

Bolshevik Revolution hadn't exiled them to Paris the following year. But

communism, as Claridge notes, was the making of Lempicka, who discovered

everything she needed for her art in

Paris - Italian masterpieces in the Louvre, modernism, art

deco, ritzy fashion. La Belle Rafaela is the typical composite: lighting by

Caravaggio, tubism by Fernand Leger, lipstick by Chanel.

|

|

Lempicka's 1929 self-portrait

as a vamp in a green Bugatti is generally considered to epitomise the jazz-age

woman; it was later used on the cover of Aldous Huxley's Point Counter Point.

Forget likeness: Lempicka looks like every other one of her tubular belles. But

there is a rapacity in those hooded eyes that seems to sum up the real woman,

who could never have enough sex, cash, food or fame.

In Paris, Lempicka slept with

actresses, prostitutes, ambassadors and sailors. She drank gin fizzes with

deposed royals, threw colossal parties where naked girls were hired as human

caviare dishes and worked at least as hard on her media profile as her art. When

Lempicki left her, she replaced him with a Hungarian millionaire who doled out

the money and asked nothing.

Baron Kuffner arranged her

second escape, to America

in 1939, where they hired King Vidor's former home in

Beverly Hills

before settling in a palatial duplex on

New York's

Fifth Avenue. Lempicka took to Manhattan with extraordinary glee, getting her

name in all the gossip columns as the 'Baroness with the Brush'. Until abstract

expressionism conquered the market in the Fifties, her machine-age style still

held good among the rich and famous subjects of her portraits. As a social

climber, her only rival was Andy Warhol, with whom she later claimed a

friendship.

It wasn't true, of course, any

more than her 'relationship' with Greta Garbo or her singlehanded invention of

art deco. Lempicka was a dreadful liar, pretending for years that her daughter

was her sister so she could fib about her age. Sometimes, she denied the child's

existence: 'I have no children; my children are my paintings.' Kizette Lempicka

was ignored, rebuked or kicked by her mother even into middle age.

Claridge has had a rough time

with Lempicka, too. There are very few letters, no journals and only a handful

of living sources, most of them creepy roués or crawling dealers. Claridge is a

meticulous, scholarly and sympathetic biographer who would love to find evidence

of Lempicka's grief when Kuffner died but is reduced to naming the florist for

the funeral. Indeed, Lempicka only comes into focus at the end of the book and

then, I'm afraid, in the words of a journalist who interviewed this

still-glamorous termagant at her final home in Mexico.

But Lempicka's art is the true

justification for this biography and here Claridge is ecstatic in her estimation.

She raves about Lempicka's dodgy drawing, compares her with Hopper and Rivera,

speaks of her in the same breath as Bellini and Vermeer. Lempicka's undeniable

gift for graphic illustration is continuously downplayed in the rush to

emphasise the dubious originality of her painting.

Claridge even proposes that the

history of modernism be revised to accommodate the uniqueness of her genius.

Here the biographer outflanks the subject. Not even Lempicka herself would have

made quite such extravagant claims for her art.

Hello to sailors, sapphists,

and a topaz as big as a fist

Tamara de Lempicka: a life of deco and decadence

by Laura Claridge (Bloomsbury, £25, 436pp)

18 March 2000

| |

Tamara de Lempicka worked with

precision. "My paintings are finished from this little corner to this little

corner," she wrote. "Everything is finished." She is best remembered for the

portraits she did in Paris in the 1920s, of assertive female nudes with limbs

entwined and faces fused. They startle because of the contrast between clarity

of form and ambiguity of relationship.

Legend has it that she herself

was a helluva girl. No previous biography has appeared. The reason for this is a

lack of letters, journals and diaries, by or about her. Laura Claridge is

undeterred.

|

|

DORMEUSE |

|

For source material she has

used Lempicka's prosy autobiographical

pieces, five books of press clippings about her shows, anecdotes from her

daughter Kizette Foxhall, what must have been hours on the phone with embalmed

White Russian émigrés who perhaps brushed shoulders with "one of the century's

most dramatic and imposing personalities", and "Tamara's ghost" - who encouraged

the enterprise with "a sudden guttural chuckle" in the author's ear.

God knows what the ghost was

laughing about. It ought to have insisted on a better book than this. Claridge's

structure is from birth to death. Between these vague events (was it 1895 or

1898, and did Lempicka's nurse murder her, or not?) all is speculation, hearsay,

gush and irritation.

No "ordinary woman", we are

told, "could stare at a man's trousered crotch with Tamara's icy elegance, a

gaze that the seductress would follow with a long drag on her ebony cigarette

holder." How on earth did Laura Claridge know? I turned to the footnote (101 of

chapter 3). "Told to the author by the very gracious Alexander Chodkieweitz in a

lengthy, delicate and sometimes awkward phone conversation."

Chodkieweitz also remembered

that Lempicka's "favourite sexual activity was to be caressed over her very

colourful, very excitable nipples and genitals by a beautiful young woman, while

she performed similar activities on the most handsome sailor in the group. After

such nocturnal stimulations, she returned home full of confidence and insight -

and cocaine - and in a frenzy painted until six or seven am. After several hours

of sleep and a quick breakfast with Kizette, she resumed her daily routine of

art classes and café socialising before preparing to begin her night life anew."

Then there is testimony from

"the cynical George Schoenbrunn", who told the author that Lempicka smelled and

left derisory tips in four-star restaurants. And Countess Maria Suzpuchiana who,

from the Hotel Capri in October 1997, revealed that Lempicka went to seedy Paris

night-clubs 70 years previously "fondling quite openly a beautiful working-class

boy one night and a girl the next". Such anecdotes lead Claridge to assert that

"no one could fetishize sex or orchestrate desire as well as [Lempicka]".

This is one way of writing

biography. I searched the tosh for what might be true about Lempicka, beyond the

strength and presence of her work, insufficiently represented here with only 16

plates. She was born in Moscow of Polish and Russian/Jewish parents. Her family

name was Gorski. When she was 15 she met Tadeusz Lempiki. "When Tamara

encountered Tadeusz at the costume ball in 1911, he had recently graduated from

law school and was now free to frolic."

They married in 1917, then went

to Paris with their baby daughter to escape the Bolsheviks. She determined to

earn her living from her work. She copied Michelangelo and Botticelli to learn

technique and in the Twenties painted those nudes that fill the canvas, without

background, sculpted and hefty.

Her work was well-received in

the 1925 Art Déco exhibition in Paris and in solo exhibitions. She seemed not to

figure in the well-documented salon life of famous lesbians of the time, such as

Gertrude Stein, Natalie Barney or Winnaretta Singer. She said she kept a

detachment from café life because she was busy working.

Tadeusz left her in 1927. He

went to Poland and married another woman. In Lempicka's valediction portrait he

wears an overcoat and, hat in hand, turns his back on the city. After Tadeusz,

she married Baron Raoul Kuffner de Dioszegh, who liked to hunt and attend to his

land holdings. He bought her paintings between 1929 and 1933 and made her rich.

Her modernist house in rue Méchain was of glass and chrome, with her initials

woven into the cushions and a dining table for 20.

Before the Second World War,

she and the Baron moved to America. In the Forties she painted still lives,

inspired by Dutch and Flemish art, but little interest was evinced in them. She

had solo retrospective exhibitions at respectable galleries, but seemed to move

from painting to a leisured life.

Her Manhattan apartment cost a

quarter of a million dollars in 1942 and was filled with gilt furniture and gold

drapes. She liked her luggage to match her limousine, and in photographs looks

like the vulgar rich. She had posh houses in Havana, Palm Springs, Manhattan and

Paris. In old age she was a bit of a fright, bedecked in floral dresses with

matching hats, and too much gold.

As for her moods and feelings,

or who she was in any living sense, it is hard to know. According to Laura

Claridge she "had a probable manic-depressive alternation in her mental cycles",

"would sink into a panicked silence at the very mention of communism", and had

"an intuitive response to beauty and the realm of the senses".

It is also not clear what form

she gave to the decadence and lesbianism suggested by her work. It would be

interesting to find out what was going on in the portraits she painted and in

her private relationships.

The poet Gabriele D'Annunzio

wrote saucy letters to her and gave her a topaz the size of a fist, but he did

the same to Romaine Brooks and Radclyffe Hall. She had some kind of intrigue

with Greta Garbo, but so did Cecil Beaton.

Laura Claridge states that one

of Lempicka's models in Paris, Ira Perrot, "was possibly the major romantic

attachment of her life", but divulges nothing of this relationship. Such

assertions do not recreate Lempicka. But, whoever she was, glitzy people like

Madonna and Barbra Streisand now pay millions of dollars for her bold, sensuous,

forceful paintings.

Diana Souhami's 'Gertrude and

Alice' and 'Greta and Cecil' have been republished by Weidenfeld

Portrait of a far from still

life

Tamara de Lempicka by Laura

Claridge, (Bloomsbury £25)

26 March 2000

| |

Although I spent four years at

the Chelsea School of Art, I had never heard of Tamara de Lempicka until I read

Laura Claridge's biography. Her reputation has been undeservedly ignored. "No

doubt art histories would treat the painter less skittishly if she had been

attached to a struggling, significant male painter," writes Claridge. "From the

end of World War One until the 1960s, no major female painter would succeed

commercially unless she was linked to a prominent male artist whose interest in

her was sexual as well as professional."

Tamara was born at the end of

the 19th century in Moscow. She was from an aristocratic Polish family and had

some Jewish blood, a fact she chose to conceal, together with her age and

birthplace. She married Tadeusz Lempicki, by whom she had a daughter, Kizette.

She escaped the Bolshevik Revolution at 20 or so, with the help of a Swedish

consul who forged papers for her and later got her husband out of the country in

return for sex. This was the first of a long series of liaisons. Eventually she

was reunited with her family in Paris, where she became an artist almost by

chance. While most of the aristocratic émigrés made a living by modelling, she

realised her body was too curvaceous, so she took art lessons instead.

|

|

|

Lempicka's early paintings were

signed with the masculine sounding T de Lempitsky. They are cubist works in the

manner of Léger, but with a sensual sheen to the skin that is reminiscent of

Ingres or Renaissance Italian painters. While allying herself to modernism,

Lempicka liked to use old techniques, pricking out her outlines on canvases or

panels, heavily coated with gesso. Her monumental nudes fetch the highest prices

these days - Lempicka was an admirer of the human form.

While she sold paintings, she

was also socialising frenetically: "What other housewife sniffed as much

cocaine? Or danced with her pelvis grinding into whatever man or woman partnered

her? Nor could any ordinary woman stare at a man's trousered crotch with

Tamara's icy elegance." Tadeusz, the cuckolded husband, turned into a sullen

wife-beater and eventually left her for a more average marriage. There is a

striking portrait of him, minus his wedding ring: The Unfinished Man.

Tamara's second marriage, to

the Baron Kuffner, seems to have been happier. He respected her as an artist and

bankrolled her extravagant lifestyle. They both travelled and had their own

sexual partners, strings of them. He sailed or hunted while she dressed

flamboyantly, painted and partied. An obsession with food and sex runs through

Lempicka's life and work. Sometimes she ate the still lifes she was supposed to

be painting. At parties, in her lesbian phase, she indulged in midnight meals of

food arranged artistically on the bodies of her girlfriends.

As Europe went to war, the

Kuffners emigrated to Hollywood, a congenially decadent scene. Though Lempicka

eventually left California to live on the East Coast, her work has frequently

appealed to stars. In later years, Madonna, Jack Nicholson and Barbra Streisand

were among the discerning few to recognise its quality.

Lempicka's style continued to

change and develop throughout the following decades. But her glossy still lifes

and her thick palette knife paintings were less admired than the early work. As

Lempicka aged, she had to come to terms with both loss of looks and loss of

artistic reputation. Her last years were spent in a house in Mexico where she

had hoped her daughter would join her. Although she loved Kizette, she had

dominated her throughout her life while lavishing money on her. As a kind of

blackmail she made a series of wills, sometimes cutting her out completely. In

the final one, half her paintings were left to a young Mexican artist, Victor

Contreras, who was with her at the end. He had the task of scattering her ashes

from a helicopter into Mount Popocatépetl. Claridge ends somewhat sentimentally

with a vision of him: "Staring at the luminescent veil of volcanic ash

shimmering on Cuernavaca's narrow stone streets, he sighs fondly: 'Tamara

darling, you never know when to stop.'"

October 24, 1999

Glitter Art

The life of a Deco

painter who was as sybaritic as her subjects.

TAMARA DE

LEMPICKA

A Life of Deco and Decadence.

By Laura Claridge.

Illustrated. 436 pp. New York:

Clarkson Potter Publishers. $35

By GLYN VINCENT

| |

PORTRAIT OF A

YOUNG GIRL IN

A GREEN DRESS |

|

Jean Cocteau once said of the painter Tamara de Lempicka that she loved ''art

and high society in equal measure.'' If her pursuit of society resulted in

opened doors and enviable pleasures, two-timing the art world would also prove

to be the bane of her existence. ''To artists she appeared to be an upper-class

dilettante, and to the nervous haute bourgeoisie she seemed arrogant and

depraved,'' Laura Claridge writes in ''Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and

Decadence.''

A Polish-Russian aristocrat, Lempicka barely escaped the Bolshevik

Revolution. In 1918, she landed in a drab little hotel room in Paris with her

unemployed husband and a small child. Within a few years, marshaling her innate

talent, her wit and Greta Garbo looks, she became the most talked about Art Deco

painter of her time. To this day, her erotic portraits of stylish sybarites are

enduring testaments to the novelty-loving materialism and decadence of the

glittering 1920's.

There was nothing ordinary about Lempicka;

even her name clings to the tongue like an exotic marmalade. Flamboyant

(paradoxically remaining true to herself while being a slave to fashion) and

imperious, she pinned down her husbands like butterflies in a case, gave lavish

parties for hundreds and indulged in every vice that came her way.

|

|

In the Paris salon of the poet Natalie Barney, she

sniffed cocaine and drank sloe gin fizzes laced with hashish among the likes of

Andre Gide. On the banks of the Seine, she picked up sailors and female

prostitutes. After her nocturnal debauches, she painted until dawn. Her life

style (and her ''affair'' with the Italian poet Gabriele D'Annunzio) sent her

first husband, Tadeusz Lempicki, packing into the arms of a plump heiress.

Lempicka's second marriage was to the Hungarian Jewish Baron Raoul Kuffner,

which necessitated a second flight, this time from Hitler's Europe to the United

States. In New York and Hollywood (where she was known as ''the Baroness with a

paintbrush'') she saw her career rise and plummet -- only to have her work

rediscovered in the 1970's and 80's (she died in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in 1980)

and collected by celebrities like Madonna and Jack Nicholson.

It is Claridge's ambition that Lempicka, whom she calls ''one of the 20th

century's most important and iconoclastic artists,'' be returned to her rightful

place in the limelight. But her rush to enshrine Lempicka in the pantheon of

modern art's greatest masters sometimes results in breathy pronouncements and

lapses of judgment that disrupt an otherwise lucid and interesting account of

Lempicka's life and art.

In uncovering Lempicka's life, Claridge, the author of ''Romantic Potency:

The Paradox of Desire,'' has surmounted a serious handicap. There were no

diaries and few letters and documents to consult; most previous accounts of

Lempicka's life have been based on her deliberate lies and improvised anecdotes.

Claridge establishes that Tamara Gurwik-Gorska was born around 1895 in Moscow --

not, as she insisted, in 1898 (or later) in Warsaw. Her mother, Malvina Dekler,

came from wealthy Polish bankers; her father, Boris Gurwik-Gorski, was a

successful Russian Jewish merchant. He disappeared early in Lempicka's

childhood, and she fairly well erased him and her Jewish heritage from her

memory. She grew up in the hierarchical, class-conscious atmosphere of the

haute bourgeoisie during la belle époque. She attended finishing

school, visited Warsaw, St. Petersburg, Paris, and made annual tours of Italy,

where she first fell in love with the Renaissance masters that were to become an

important influence on her work.

By 1910, Lempicka was spending most of her time at her wealthy aunt's opulent

residence in St. Petersburg. It was there that she acquired her taste for

luxury, and, at a costume ball, she set her sights on her future husband, a

handsome Polish lawyer named Tadeusz Junosza-Lempicki. The couple's idyllic,

spoiled existence -- traipsing from avant-garde cafe gatherings to society teas

-- was cut short by the Russian Revolution. The Cheka arrested Tadeusz, and

Lempicka was left to her own devices to free her husband and escape to Paris.

''Paradoxically,'' Claridge writes, Lempicka the painter ''would not have

existed without the Russian Revolution. Her expulsion from a predestined life of

privilege transformed her into a modern woman.''

In Paris, Lempicka, who had early on shown talent as an artist, took up

painting to support her family. To a sleek Cubist style she added the

disciplined finish and melancholy light of Renaissance painting. She painted

beautiful if somewhat dim-looking women -- half mannequins, half animals, with

blood red lips and translucent eyes staring Belliniesquely at heaven, awaiting,

it seems, not a message from God but an elixir to slake their restless ennui.

By the mid-20's, Lempicka's portraits of aristocrats and prostitutes were

being exhibited in the Paris salons. Her ''Autoportrait: Or, Woman in the Green

Bugatti'' (1929) was so often reproduced it became a sort of advertisement for

the new modern woman -- independent, stylish and sexually liberated. Lempicka's

success allowed her to mingle with avant-gardists like Jean Cocteau, Salvador

Dali and Filippo Marinetti, but she remained disengaged from the progressive,

leftist artistic climate of her time. Aloof and wild, she was fundamentally

anti-intellectual. At home, too, she remained at sea. An absent wife, she used

her artistic life to excuse her infidelities. A rigid perfectionist, she abused

her daughter, Kizette. After her first marriage fell apart she suffered from

severe bouts of depression that were to plague her for the rest of her life.

By the mid-1930's the neo-classical and decadent elements of Lempicka's

painting made her suspect to both the left-wing critics and the fascists.

Lempicka's place in the art world would not be resolved by her move to the

United States in 1939. With her wealthy second husband's money she continued her

frenetic socializing, while her representational painting quickly became an

anachronism, overshadowed by Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. In the

1960's she largely gave up her career and came to resemble a demanding,

eccentric socialite more than an influential painter.

Claridge argues that Lempicka has been denied her rightful place in modern

art history because she was a woman whose background was politically incorrect,

and suggests a re-examination of Modernism is in order. She may not be up to

that task, but she has contributed a well-deserved and sympathetic account of

Lempicka's life.

Glyn Vincent is writing a biography of the artist Ralph

Albert Blakelock.

POLISH

LIBRARY IN WASHINGTON

| |

A casual

reader of Polish painting in the 20th century may have only a limited idea of

Tamara Lempicka's life and her contribution to the Deco history of the 20s and

30s, and thus this excellent biography will be a revelation. Her prominence was

primarily recognized in Western Europe and America, where she spent most of her

creative life. Firstly, there is her irrepressible individuality that

fascinates. She was an “artiste” to the core, and it is often difficult

to figure out the dividing line between reality (read: facts) and legend (read:

Tamara's fantasies.) Was she born in Warsaw or in Moscow? Perhaps in 1898 but,

maybe in 1896 or some other year. We know very little about her father, Boris

Gurwik Gorski; her mother was Malwina Dekler, a well-to-do Pole of French

descent. Her teen years were certainly exciting, as she divided her time between

the French Riviera chic and the splendors of St. Petersburg salons, where she

met the handsome Tadeusz Lempicki; she fell hopelessly in love and married him

just before the Revolution overtook Russia. Their escape with the baby to France

was a true odyssey. And here, in Paris, her career began.

Unquestionably she had a formidable talent for painting and also amazing energy.

Her erotic works are not to everybody's liking, but her portraits are stunning.

Soon she was in the forefront of Deco art, which marked a world event in

architecture as well as other art forms. Secondly, she showed stamina when

fighting against odds facing any painter. This was evident when she escaped from

France via Portugal to America in 1940 and had to start from scratch.

|

|

AUTORETRATO |

|

Amazingly, she moved to Hollywood and became star-struck. Soon Tamara was the

talk of the town. A musician can earn his living by playing every night to a

different audience or an actor by moving from town to town. But a painter

depends entirely on admirers' who buy specific works. Fortunately for Tamara,

she had some outside resources, but one suspects she would have succeeded even

without them.

Post-war

years brought various experiences to this exceptional woman. At one point the

Deco style was considered "passé”; Tamara was getting old, and an

adjustment to new realities was not easy. Her ultimate retirement to lovely

Cuernavaca south of Mexico City was probably a blessing for her.

There were

many aspects of Tamara. Her escapades in Paris were not particularly ennobling,

to put it mildly. Her affair with the celebrated Italian poet d'Annunzio may be

perhaps excused, as the old rascal obviously took advantage of her. She parted

from her first husband Lempicki who went to Poland while she retained his name

in her painting career. She then married a rich Hungarian baron who became a

refugee in the U.S. but still with substantial means. One wishes that she had

treated her devoted daughter better.

Here is an

interesting footnote; eight years ago a popular book entitled Glass Mountain

was published and the cover contained a photomontage of two paintings that were

obviously done by Lempicka but without proper credit to the artist. This serious

oversight was spotted by alert Mrs. Alina Żerańska, the Editor of our

Newsletter. The resulting commotion caused sharp exchanges between various

Polish organizations and American media. However, it also indirectly made the

reading and viewing public aware of the painter's importance on both sides of

the Atlantic as an outstanding representative of deco art, The exhibition of

Tamara's paintings along with other woman artists in Washington D.C. that took

place at the same time became a noted event.

George

Suboczewski

LA PINTORA SENSUAL

Tamara de

Lempicka es una de las pintoras con más fuerza y personalidad del siglo XX.

Venerada como una diosa en la Europa de entreguerras, sus cuadros, tan sensuales

y voluptuosos como su vida, quedaron arrinconados hasta mediados de los noventa.

03.02.2001

| |

|

|

Avasalladora, excéntrica y con un gran talento, la pintora Tamara de Lempicka ha

sido una de las personalidades más seductoras del arte contemporáneo.

Escandalizó a la sociedad de entre guerras con sus aventuras sexuales y con el

ambiente de sus fiestas, en las que no faltaban las drogas, y en las que criados

desnudos atendían a los invitados. Sus pinturas fueron clasificadas a veces de

porno blando, pero sus obras de los años veinte y treinta han sido comparadas

con las de dos grandes del siglo XX, Léger y Picasso. Hoy es una de las pintoras

más buscadas por los coleccionistas, y su influencia en muchos artistas actuales

ha sido finalmente reconocida. El hedonismo de su pintura es uno sus rasgos más

atrayentes. Algunos de sus cuadros desprenden tanta sensualidad que la leyenda

de que antes de pintarlos se acostaba con los modelos ha sentado cátedra.

El misterio

rodea su vida. Tamara de Lempicka se dedicó a falsear su propia identidad

sembrando de mentiras toda su biografía. Ocultó hasta su fecha de nacimiento,

probablemente en un gesto de coquetería. Se calcula que nació entre 1894 y 1902.

Unas veces afirmaba haber nacido en Polonia, otras en Rusia. Por eso,

reconstruir la vida de Tamara, nombre que le dio su madre en recuerdo de la

heroína de un poema ruso, ha desanimado a más de un biógrafo. Hasta que una

profesora norteamericana, Laura Claridge, consiguió despejar la leyenda de la

realidad y ha escrito la que puede ser su biografía definitiva.

|

|

| |

Group de Quater nus |

|

|

|

El

resurgimiento de esta pintora se dio el 19 de marzo de 1994 gracias a la subasta

de la colección de arte de Barbra Streisand cuando, en la sala Christie's de la

Quinta Avenida, apareció el cuadro Adán y Eva, pintado por De Lempicka en 1931,

y un grito se levantó entre el público. La sensual y luminosa pintura fue

adjudicada en dos millones de dólares. Con esto, el afán de poseer un Lempicka

se apoderó de Hollywood: Jack Nicholson, Madonna y Sharon Stone ya han comprado

sus obras.

Tamara de

Lempicka es una de las principales pintoras del siglo XX, pero también una de

las más olvidadas. Su nombre no aparece en ninguna de las principales

enciclopedias de arte moderno. Influenciada por los cubistas franceses y por los

maestros del Ranacimiento, se inventó su estilo propio que etiquetaron como art

déco. Cuando vivía en París se pasaba horas y horas en el Museo del Louvre

delante de los cuadros de sus admirados Bellini y Caravaggio para intentar

captar el efecto translúcido de sus pinturas, recordando el viaje que a la edad

de 12 años hizo con su abuela desde su Polonia natal hasta el sur de Italia. El

descubrimiento de Boticcelli fue para su mirada ingenua un fogonazo, y su

influencia la marcó para el resto de su vida. Eso, y las clases de pintura que

recibió en Montecarlo mientras su abuela jugaba a la ruleta en el casino.

Su vida no

presagiaba una dedicación a las artes. La joven Tamara se integró en la rica

sociedad de San Petersburgo, donde acudía con frecuencia a visitar a sus tíos.

Fue ahí, en un baile de disfraces en 1912, donde conoció a un joven y elegante

abogado llamado Tadeusz Lempicka, con el cual se casó. Pero el matrimonio

sufriría los efectos de la revolución bolchevique. Una noche la policía secreta

entró por sorpresa en la casa y detuvieron a Tadeusz por actividades

contrarrevolucionarias. Cuenta Claridge que la impresión que sufrió Tamara ante

esos policías con chaquetas de cuero negro fue tal que la persiguió de por vida.

Consiguió escapar de Rusia, pero ya nada volvió a ser lo mismo. Cada vez que en

su presencia se mencionaba la palabra comunismo, Tamara palidecía. A partir de

entonces decidió, como Scarlet O' Hara ante las ruinas de Tara, que nunca más

pasaría hambre ni privaciones.

Sonntag, 14. Juli

2002 Berlin, 13:32 Uhr

Die

Versiegelung der Oberfläche

Sie verband

handwerkliche Präzision mit gesellschaftlichem Glamour: Schon zu Lebzeiten war

die Malerin Tamara de Lempicka der Liebling der Schickeria. Daran hat sich bis

heute nichts geändert

Von Ulla Fölsing

| |

Erotisch, kühl und

an Luxus gewöhnt: So waren die Frauen, die Tamara de Lempicka malte, und so war

sie selbst. Seit der ersten "Art déco"-Ausstellung 1925 galten ihre Bildnisse

als Inbegriff des Lebensgefühls im neuen, technischen Zeitalter. Für ein

Jahrzehnt war die Malerin der Star der Pariser Schickeria. Ihr Selbstporträt

"Frau in grünem Bugatti", 1929 Titelbild einer Gesellschaftszeitschrift und

danach immer wieder abgedruckt, wurde zur Hymne auf die Emanzipation, die

Amazone am Lenkrad zur Ikone von Geschwindigkeit und Freiheit.

Von der akademischen

Kunstgeschichte wird die skandalumwitterte Polin, die sich so lässig in Szene zu

setzen verstand, bis heute kaum beachtet. Fans von Lempickas plakativer Ästhetik

stört das wenig: Sammler wie Wolfgang Joop, Jack Nicholson und Madonna reißen

sich um Lempickas Bilder. Sie scheinen eine gute Kapitalanlage: Im Mai hat

Sotheby's New York Lempickas Gemälde "La Musicienne" von 1929 angeboten. Die

stattliche Jazz-Age-Heroine in Blau war auf gut eine Million Dollar angesetzt.

Sie ging schließlich für 2 649 500 Dollar weg - und hat damit ihren Preis

beinahe verdreifacht. Das scheint inzwischen fast die Regel bei Bildern aus

Lempickas entscheidender Pariser Zeit: 1994 verkaufte Barbara Streisand bei

Christie's Lempickas Duo "Adam und Eva" von 1931 für 1,8 Millionen Dollar.

Geschätzt worden war es auf 600 000 Dollar.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Kizette au balcon |

|

Für den muskulösen,

männlichen Part bei diesem paradiesischen Paar, das eher nach Pin-up denn nach

Bibel aussieht, holte Tamara de Lempicka 1931 einen Verkehrspolizisten in ihr

Pariser Studio. Ebenso ungeniert wie ihre Bilder inszenierte die Malerin die

eigene Person und ihr Leben. Die kürzlich erschienene Biografie von Laura

Claridge (S. Fischer Verlag) demaskiert Lempickas Selbstentwurf der Tochter aus

reichem Haus. Danach wurde Lempicka nicht im Warschauer Großbürgertum, sondern

als Kind eines vermögenden Moskauer Juden geboren. Ihre Tochter Kizette gab sie

als Schwester aus. Das adelige "de" setzte sie nach ihrer Flucht vor der

Oktoberrevolution nach Paris vor ihren Ehenamen.

Die exzentrische

junge Frau, die stets auf großem Fuß lebte, machte in Frankreich aus ihrem Hobby

einen Brotberuf: Mit 28 Jahren hatte sie mit ihren Bildern die erste Million

verdient, auch durch ihre zähe Energie als Geschäftsfrau und ihren Sinn für

Skandale - ihre publikumswirksamen Affären waren zahlreich. Eine hatte sie mit

dem italienischen Dichter Gabriele d'Annunzio: Lempicka bezeichnete den

Mussolini-Getreuen zwar als "altes Männchen in Uniform", nutzte seine Prominenz

aber für ihre eigene Publicity.

Ende der zwanziger

Jahre verglich der französische Kunstkritiker Arsène Alexandre Lempickas

handwerkliche Präzision und die makellos glatten Oberflächen ihrer Bilder mit

dem Können von Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. Lempicka hatte ihren Malstil von

den italienischen Gemälden der Renaissance übernommen, deren Schönheit und satte

Farben sie seit frühester Jugend bewunderte. Ihre neoklassizistische, dem

Zeittrend konträre, unsichtbare Pinselführung stand dabei in reizvollem Kontrast

zu der modernistischen Tektonik ihrer Gestalten und den kubistischen Formen

ihrer Hintergrundmalerei.

Spätere Werke sahen

anders aus: Ab 1939 lebte die Künstlerin mit ihrem zweiten Mann, dem ungarischen

Baron Raoul Kuffner, in den USA. Dort malte sie Religiöses, Stillleben und -

wenig überzeugend - abstrakt und in Spachteltechnik. Bilder aus dieser Zeit sind

deutlich billiger zu haben: Im Februar 2002 bot Sotheby's in New York Lempickas

"Nue au bras coupé" von 1951 (siehe Abb.) für geschätzte 15 000 bis 20 000

Dollar an. Die dickliche Nackte ohne rechten Unterarm wurde zum Preis von 26 625

Dollar zugeschlagen. Es scheint, dass Tamara de Lempicka in der Neuen Welt als

Malerin den Biss und die Orientierung verloren hatte. Tatsächlich waren die vier

Jahrzehnte in den USA bis zu ihrem Tod 1980 von künstlerischem Misserfolg

geprägt. Die Folge waren Depressionen, die die gealterte Femme fatale mit

angestrengtem Gesellschaftsleben überspielte. Ein Star, wie einst in Paris,

wurde sie nie mehr wieder.

12.07.2002

11:44

Tamara de

Lempicka-Biografie

Venussonde

Laura

Claridge studiert die lebenstüchtige Tamara de Lempicka

JÖRG HÄNTZSCHEL

LAURA CLARIDGE:

Tamara de Lempicka.

Ein Leben für Dekor und Dekadenz. Aus dem Englischen von Irmengard Gabler. S.

Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2002. 478 Seiten, 24,90 Euro

Das Leben erzählt nicht nur die schönsten Geschichten, das Leben ist das

eigentliche Meisterwerk. So etwa könnte man die verbreitete Haltung beschreiben,

aus der sich die seit Jahren anhaltende Hochkonjunktur für Biografien erklärt.

Es ist weniger das Leben als Spiel des Schicksals, das so fasziniert, sondern

das Leben als Produkt einer buchstäblich ausgelebten Autorschaft. Nicht am Grad

der Authentizität wird es gemessen, sondern an der Cleverness und

Inspiriertheit, mit der es konstruiert wurde. Nicht die Pflicht mühsamer

Selbstfindung ist von Interesse, sondern die Kür spielerischer Selbsterfindung.

Die polnischstämmige Malerin Tamara de Lempicka, bekannt durch einige wenige

ikonische Bilder, die immer wieder auf Buchcovern, in Postershops und in

Madonna-Videoclips auftauchen – seltener im Museum – beherrschte diese Kunst

lange bevor sie zum Klischee der Postmoderne wurde. Ihr Künstlerleben war eines

des Wollens, nicht des Müssens.

Die amerikanische Kunsthistorikerin Laura Claridge hat sich jetzt mit Akribie

und ohne ironischer Distanz durch das Geflecht von Tatsachen, Fabrikationen,

Legenden und Klatsch gearbeitet. Nicht Enthüllung ist ihre Methode, sondern ein

close reading von Fakten und Fiktionen, die etwa gleichen Anteil am Phänomen

„Tamara“ haben.

Dabei hatte Tamara de Lempicka Ausschmückung eigentlich nicht nötig. Geboren

wahrscheinlich 1895 in Moskau – nicht 1898 in Warschau, wie sie behauptete –,

durchlebte sie sämtliche Höhen und Tiefen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Ihre Kindheit

verbrachte sie im aristokratischen Milieu des Warschau der belle époque. Man

lebte wie bei Proust; monatelange Bildungsreisen nach Italien, das

Mädchenpensionat in Lausanne, die „Wintersaison“ in St. Petersburg und Abstecher

nach Cannes waren selbstverständlich – bis jäh das Ende der goldenen Jugend

hereinbrach. Blind für die Radikalität der zukünftigen Revolutionäre flirtete

die erzmonarchistische Kunststudentin noch am Vorabend der Oktoberrevolution mit

der linken Avantgarde. Als die Barrikaden dann brannten, gelang es ihr nur

knapp, sich und ihren Ehemann, der vermutlich für die Konterrevolutionäre

arbeitete, ins sichere Paris zu bringen: das Trauma ihres Lebens. Ohne Geld,

ausgestattet nur mit Dreistigkeit und Disziplin, baute die Exilantin mit Kind

und verstörtem Ehemann aus dem Nichts binnen weniger Jahre eine Karriere als

bald auch kommerzielle erfolgreiche Malerin auf.

Die

Zwanziger Jahre wurden ihre produktivste Periode.

Bemerkenswert war nicht nur ihr einzigartiger Stil: ein skulpturaler,

neoklassizistisch umgeformter Kubismus, gleichermaßen unterkühlt wie bebend vor

Sexualität, den man etwas ratlos dem Art Déco zuschlug. Bemerkenswert war nicht

nur die Gleichzeitigkeit ihrer Pariser Existenzen: die der Gesellschaftslady,

der ehrgeizigen Jungkünstlerin und der dekadenten Femme fatale, die mit Frauen

und Seeleuten ins Bett ging, nur um am nächsten Morgen ihrer Tochter das

Frühstück zu bereiten. Bemerkenswert war vor allem ihr Talent zur

Selbstvermarktung. Um Porträtkunden zu finden, schmiss sie sich an Reiche und

Prominente wie Cocteau oder Coco Chanel. Um im Kunstbetrieb den Anschluss nicht

zu verlieren, verbrachte sie die Nächte in Cafés und auf Parties, wo sie ein

interessantes Gesicht machte, wenn Futuristen und Surrealisten wieder ihre

Utopien wälzten.

Dieser Praxis blieb Tamara de Lempicka treu, als sie sich nach der Flucht vor

den Deutschen mit ihrem zweiten Ehemann in Hollywood niederließ: ihr dritter

Neuanfang. Zielstrebig steuerte sie die Künstlerkreise an, lud Hunderte

einflussreicher Leute zu opulenten Parties, verteilte Starporträts von sich an

die Presse und lancierte Gerüchte, wie das, sie sei eine enge Freundin Greta

Garbos. Statt über ihre Bilder zu sprechen, gab sie in den Zeitungen Beauty-Tips

(„Mollige Frauen sollten breitkrempige Hüte meiden“). Zur Eröffnung einer

Ausstellung in New York, von der sie sich wieder einmal den Durchbruch erhoffte,

verbreitete sie über AP eine völlig ernst gemeinte „Lektion in der Kunst des

Flirtens“. Nicht einmal Hollywood, geschweige denn New York, wohin sie bald zog,

kamen da noch mit.

Dass sie in Amerika nie richtig Fuß fasste, lag aber vor allem an der

stilistischen Kehrtwende, die sie Mitte der Dreißiger vollzog. Statt dem kühlen

Stil ihrer früheren Werke treu zu bleiben, die im New York des Art Déco und der

Streamline-Moderne gut ankamen, statt sich dem Surrealismus anzuschließen, der

dort mit Verspätung eintraf, verlegte sie sich auf einen manierierten

Naturalismus. Sie malte sentimentale Genrestücke von verhärmten Nonnen und

verweinten Flüchtlingsmüttern, die sich stark an den niederländischen Meistern

anlehnten. Als schließlich mit dem Abstrakten Expressionismus die Leinwand

Schauplatz und der Pinselstrich Protagonist der Malerei wurden, stand sie mit

diesen – technisch wie immer perfekt ausgeführten – Gemälden vollends als

Gestrige da. Gerade sie, die ihre Karriere als Frage der Strategie und des

Gespürs für Trends verstand, hatte die Konjunktur verpasst. Während sie die

Moderne lebte wie kaum eine andere, stolperte sie über ihre tief sitzende

Romantik und ein Kunstideal aus dem Quattrocento. 1980 starb sie, exzentrischer

denn je und immer noch schwerreich, in Mexiko. Freunde streuten ihre Asche mit

dem Hubschrauber über den Krater des Popocatepetl. Sieben Jahre später hatte

„Tamara“ am Broadway Premiere. JÖRG HÄNTZSCHEL

The good old

naughty days

In life Tamara de Lempicka was a

Left Bank bisexual with an appetite for bohemian living. Her work, though,

portrays the dubious glamour and discipline of fascism

Fiona MacCarthy

Saturday May 15, 2004

The Guardian

If there is a single image that encapsulates art deco, it

is Tamara de Lempicka's self-portrait Tamara in the Green Bugatti. It was

commissioned for the cover of the German magazine Die Dame, which defined her as

"a symbol of women's liberation". The tight, post-cubist composition of the

painting; the muted, sophisticated colour; the sense of speed and glamour; her

blonde curl edging out of the head-hugging Hermès helmet; her long leather

driving gauntlets; her lubricious red lips. Clearly this is a woman who means

business - even to the extent of mowing down a few pedestrians.

Her time was

the 1920s: a period of transition, an era in which functionalism merged with

fantasy and formal social structures lurched into the frenetic. In essence, De

Lempicka was a classicist, having admired Renaissance painting since her

adolescent travels in Italy. But she astutely combined traditional portraiture

with advertising techniques, photographic lighting, vistas of the tower

architecture of great cities.

Her milieu was

the glittery and scintillating Paris of the years between the wars, a place of

high style and lascivious behaviour. With a callous authenticity, De Lempicka

depicted the shifting morals of a Paris where nothing was precisely what it

seemed. She lived and worked on the bisexual fringes of a society where there

were no rules beyond the demands of style and entertainment. She was the great

go-getter, a believer in exploiting one's resources to the ultimate. Her iconic

green Bugatti wasn't green in reality but yellow. Nor was it even a Bugatti but

a Renault. "There are no miracles," she stated with her icy realism. "There is

only what you make."

Who was she?

De Lempicka shuffled the facts of her biography much as she meddled with her

birth date. Tamara Gurnick-Gorzka was born in Moscow - or could it have been

Warsaw? - in 1898 or so, to a wealthy Polish mother and a cosmopolitan Russian

father. Her background of social confidence and ease was to prove an advantage

to a portraitist: she confronted her sitters on equal terms. In St Petersberg,

she met Tadeusz Lempicki, a tall, saturnine attorney of noble family and, at the

age of 14, announced her love for him. They were married just before the Russian

revolution. Lempicki was arrested by the Bolsheviks but his wife secured his

release.

Like other

exiled White Russians, they arrived in Paris with no money, having abandoned

their possessions. They now had a child, Kizette. Tadeusz Lempicki remained

unemployed and moody. Tamara's portrait of her husband shows the queasy

self-importance of the glamour boy displaced. These were years of deprivation,

in which Tamara herself became determined to succeed as a professional artist.

"My goal," she later wrote, "was never to copy, to create a new style, bright,

luminous colours and to scent out elegance in my models." She became a prime

interpreter of modernity.

De Lempicka's

painting is a thing of gloss and gesture. In her early days in Paris, she

enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and absorbed the work of the old

masters, especially admiring Bronzino. In some ways, De Lempicka is a mannerist

reborn. She went on to study in the studio of the symbolist Maurice Denis, a

highly decorative painter who instilled the sense of discipline and structure in

her work.

Her most

influential mentor was the painter and critic André Lhote, perpetrator of a less

strident, gentler-coloured form of cubism, a style easily acceptable to the

bourgeoisie. In her early Paris paintings, De Lempicka employed this "synthetic

cubist" method, an accumulation of small geometric planes used to startlingly

voluptuous effect in images of women reclining, women bathing, women embracing,

laconically stroking one another's thighs. The blatant display of the naked

female body was a feature of art deco - this was, after all, the era of

Josephine Baker shaking her banana skins. De Lempicka's pair of

pointing-breasted giantesses, The Friends, disport themselves in front of a

futuristic stage set of skyscrapers, a 1920s fantasy of big city sex.

But her images

of female nudity also recalled the French neo-classical tradition. Her group

painting Women Bathing is the Left Bank lesbian version of Ingres's luscious

harem composition The Turkish Bath. The critics' divination of "perverse

Ingrism" in De Lempicka's paintings did her burgeoning popularity no harm. In

real life, she acted up to it, displaying her own tall, slender, curvy body

outstretched on a divan, wearing a titillating white satin robe with marabou

feather adornments. Tamara played her own art deco goddess of desire.

She was a

workaholic, permitting interruptions in her nine-hour painting sessions only for

such necessities as champagne, a massage and a bath. She sold herself shrewdly

and by 1923 was beginning to exhibit in small galleries in Paris. The next year,

her work was shown at the Salon des Femmes Artistes Modernes in Paris, and in

1925 she had her first solo exhibition in Milan.

Her social

life advanced in parallel, displaying the full force of Tamara's "killer

instinct" (her daughter's description). There was something predatory in the way

she acquired so many lovers of both sexes, many of whom were also her models and

her patrons. The model for her painting Beautiful Rafaela was picked up in the

street and seduced with aplomb. The portrait throbs with an intense erotic

energy. The liaison continued for a year.

Tamara gave up

on Tadeusz and, brandishing diamond bracelets from wrist to shoulder, joined the

European avant-garde celebrities: Marinetti, Jean Cocteau, Gabriel d'Annunzio.

She visited d'Annunzio at his notorious villa Il Vittoriale in Gardone where,

unusually, she resisted his advances and, equally unusually, failed to paint his

portrait - a singular loss to the De Lempicka oeuvre. She was a spectacular

attender of Natalie Barney's afternoons "for women only" and claimed to have

snorted cocaine with André Gide.

Thanks to her

contacts in the world of the Paris couturiers, De Lempicka always looked

fabulous. Photographed in the right light, she could be Greta Garbo's sister.

She made her entrance at smart parties in magnificent garments donated by Coco

Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli.

In the late

1920s, De Lempicka acquired her most important patrons, Doctor Pierre Boucard

and his wife. Boucard was a medical scientist, inventor of Lacteol, a cure for

indigestion. He had become an avid modernist and already owned several De

Lempicka nudes, including her most flamboyant lesbian painting, Myrto, Two Women

on a Couch. He now offered her a two-year contract to paint portraits of

himself, his wife and daughter, also asking for an option on any other paintings

she produced.

This sudden

financial stability allowed her to buy a three-storey house and studio on Rue

Mechain on the Left Bank. She commissioned its refurbishment by Robert

Mallet-Stevens, the most brilliant French modernist designer of the time. With

its svelte grey interior, chrome fittings and American cocktail bar it gave De

Lempicka the setting of ultimate urban smartness to which she had long aspired.

A contemporary

architectural photograph shows the new studio in all its pristine glory. There

in the centre on its easel is the portrait of Madame Boucard, completed in 1931,

a sophisticated and accomplished painting that tells us as much about De

Lempicka as it does about the sitter. De Lempicka is the connoisseur of

textiles, jewels, hairstyles, the cut of the garment, the swathe of the mink

stole: no other painter of the period gives us so precise a reading of its

material values. Madame Boucard is posed like a Renaissance courtesan, her right

nipple erect beneath the oyster satin bodice. She's a figure of power, with

something of the brutal allure of Wallis Simpson. What she tells us is that

every sex act has its price.

Size mattered

in the Europe of that time. De Lempicka's male portraits show gigantic

caddishness. Spiv-shouldered Doctor Boucard, with his test tube and his

microscope, looks more the slick sharp man about town than man of healing. Count

Fürstenberg Herdringen is a glass-eyed monster in a Frenchman's navy beret. Most

frightening of all is the colossal portrait of the Grand Duke Gabriel

Constantinovich, with his gold-braided uniform and empty, sneering face.

De Lempicka

was an artist of the Fascist superworld: her portraits were allied to the "call

to order" movement, the return to monumental realism in European art. Her art

exudes the dark and dubious glamour of authoritarian discipline. When she paints

the Duchesse de la Salle, the Duchess is in jackboots, one hand thrust in her

pocket in an attitude of menace. It is a tremendous portrait, painted with the

sheer theatrical enjoyment, the unerring sense of decor, of De Lempicka's best

work.

In 1933 she

remarried. Baron Raoul Kuffner was the owner of vast estates donated to his

family of stockbreeders and brewers by Emperor Franz-Josef for supplying the

Hapsburg court. De Lempicka had already portrayed her future husband as a dandy

desperado, gazing out inscrutably from behind hooded lids. She had also painted

- and in doing so disposed of - his previous mistress, the Andalusian dancer

Nana de Herrera, selecting her as model for the most overtly decadent of the

"damned women" in the notorious Group of Four Nudes .

De Lempicka

was never a consistent painter. As with many ruthless people, her swagger could

give way to a strain of awful mawkishness: cubism and kitsch. Once she became

Baroness Kuffner, Tamara lost direction. The urge for fame, and indeed

subsistence, left her. The age of art deco, in which she thrived, was over. Her

sentimental studies of old men with guitars and lachrymose mother superiors are

a dreadful anti-climax after the bitchy candour of her portrait of lesbian

nightclub owner Suzy Solidor.

The political

terrors of Europe in the 1930s were impinging: she and the baron, on holiday in

Austria, were appalled to have their breakfast on the hotel verandah interrupted

by a singing parade of Hitler Youth. In 1939, urged by Tamara, who was partly

Jewish, Kuffner sold his estates in Hungary and they moved to the US. In New

York, she tried abstract expressionism unsuccessfully, and was reduced to the

role of a chic curiosity, "the painting baroness".

De Lempicka

died in 1980 in Mexico, having directed that her ashes be scattered over the

crater of volcanic Mount Popocatepetl. The woman who in her lifetime was

described as "a little hot potato" came to a suitably inflammatory end. Her

expensively dressed rogues gallery of portraits, though hardly great art, add up

to a unique and alarming social document, recording the seductive surface

textures of a European society en route to self-destruct.

Tamara de

Lempicka: Art Deco Icon is at the Royal Academy, London W1, until August 30.

Details: 0870 848 8484.

| |

|

|

EXCERPT

Tamara de

Lempicka

A Life of Deco and Decadence

By LAURA CLARIDGE

|

|

|

|

Mythical Beginnings

| |

By early

afternoon on 19 March 1994, Christie's main auction room at 502 Park Avenue in

New York City was filled to capacity. Emanating scents from the thirties—Chanel

No. 5, Joy, and the newly revived Arpège—several expensive-looking women,

craning their necks to study the forlorn latecomers standing in the back, seemed

more interested in the company they were keeping than in the objets d'art. In

the middle of the crowd, three drag queens, vamping the roaring twenties in

their gold lamé gowns and feather boas, examined the lavish catalog. Their

exasperated comments suggested that the presale estimates were higher than they

had anticipated. For days the wealthy potential buyers (carefully targeted by

Christie's thorough preregistration) had been attending publicity events—dinners

and video shows—that emphasized the glamorous, high-profile nature of this sale.

Christopher Burge, Christie's crisp British president, took his place at the

front of the suddenly silent room, and the dais began to rotate as one exquisite

object after another sold quickly, most of them for predictable prices. Gustav

Stickley furniture, Tiffany lamps, Jacques Lipchitz paintings: the spotlight

lent each item the Hollywood glow of the collection's owner, Barbra Streisand.

As the digital board at the front of the room lit up with Japanese, French, and

German currencies competing against the dollar, the wood-paneled room seemed to

hum with excitement. |

|

|

|

Suddenly a

collective gasp escaped the audience. Tamara de Lempicka's Adam and Eve, painted

at the end of 1931, shimmered at the front of the room, its impossibly luminous

nudes confounding even those who believed themselves inured to the old-fashioned

finish that pre-Modernist artists had valued so highly. Dealer Michel Witmer

nodded a bit smugly; he had already provoked many arguments by contending that

this painting would prove the crowning jewel of the show. In the face of his

colleagues' disbelief, Witmer, adamantly maintaining that Adam and Eve was not

painted on canvas, insisted that the preternatural glow of the flesh tones could

only result from oil on wood. After all, he had said, "during the 1920s,

Lempicka spent hours at the Louvre on a weekly basis studying what she

considered the masterpieces of light and color. Clearly she was influenced by

the sixteenth-century Dutch paintings that achieved a translucence in their

figures partly due to painting on panels."

"What am I

offered for this extraordinary panel painting by Art Deco's most famous

portraitist, Tamara de Lempicka?" Mr. Burge quietly but imperiously began. As

the numbers climbed rapidly from the already extravagant presale estimate of

$600,000, the room filled with chatter. Promoting the painting, the auctioneer

alluded to the peripatetic life that had inspired the artist's dramatic works:

Warsaw, St. Petersburg, Paris, Milan, and Cuernavaca. As if on cue, a spate of

international phone bids raised the price even further. When the offer reached

$1 million, the room grew tense. Numbers were flying on the digital printout,

and everyone watched Michel Witmer to see how far his client would go. A woman

dealing by phone for her Saudi Arabian collector offered $1.25 million; turning

toward Witmer, Christopher Burge intoned, "One point five?" The dealer nodded.

Back to the phone: the anonymous caller raised her bid to $1.8 million. After an

almost imperceptible sign from his client, Witmer shook his head, refusing the

offer to exceed $1.8 million. "Going once," the audience heard, "going twice . .

. sold for one point eight million dollars." With commissions added, the final

sale was $1.98 million.

On that mild

March afternoon when the gavel sounded in Christie's main salon, one of the

twentieth century's most important and iconoclastic artists was returned to the

limelight after a long hiatus. Years of comparative obscurity would yield to

public scrutiny as the painter's reputation began its most significant

reevaluation in over fifty years. Tamara would have loved and hated the whole

affair. Money defined artistic worth in her world: she had refused to sell

paintings when the offers insulted her pride. Both the sale price and the

international flavor of the bidding would have pleased the painter who lived her

life as a citizen of the world. But had she been accosted by the reporters on

her exit from the room (as the underbidder for the painting was), she would have

raged at their implication that she was being rediscovered, and at their

suggestion that her talent increased in proportion to her Hollywood connection.

Celebrity was something she appreciated. She had, in the late 1930s, enjoyed

socializing with the members of the movie industry, but she had never thought

them great judges of art. During the two years she lived in Los Angeles she was

known as the Baroness with a Paintbrush, an epithet that motivated her to move

to New York in the hope of reestablishing her reputation as a serious artist.

A mere four

months after the auction at Christie's, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts held a

Lempicka retrospective. Art historian Robert Rosenblum enthusiastically observed

that Tamara was "a liberated woman and she was frankly erotic . . . a thinking

woman's Léger." But in a review entitled "The Price Will Go Up, Tamara,"

Newsweek's art critic, Peter Plagens, referred to the painter as "practically

forgotten," producing "almost soft porn," with only "eighty-four paintings known

to exist." (Minimal research would have revealed the current count of almost

five hundred.) Tamara, he pronounced, was "the end product, not the producer of

art that influences other artists."